KLL team outside their new headquarters. Photo courtesy Kathmandu Living Labs.

By Naomi Bloch

Today, November 18, marks the 16th annual GIS Day. Throughout the week, Geothink has been presenting a series of posts looking at some of the ways in which our collaborators, partners, and friends around the world are critically examining and using GIS as a tool for civic engagement and understanding.

The community snapshots presented this week highlight diverse perspectives and uses for GIS. We conclude our series with the following piece on humanitarian mapping and OpenStreetMap.

This past March, Nama Budhathoki, a long-time contributor to OpenStreetMap, announced his candidacy for the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) Board of Directors. Budhathoki, the executive director of Nepal’s Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL), posted a manifesto that — in the months following Nepal’s April 25 earthquake — seemed beyond prescient. In it, he proposed his vision for HOT, and for the crowdsourced mapping community around the world.

Budhathoki’s principal message is two-fold. 1) Humanitarian mapping can be more effective by transitioning from being primarily a reactive community to one that encourages mapping communities to develop where they’re most needed — before crisis strikes. 2) A unique benefit of crowdsourced mapping stems from its role in community engagement and capacity building.

OpenStreetMap’s U.S. Chapter is a Geothink partner. Geothink recently caught up with Budhathoki while he was visiting Washington D.C. as the invited featured speaker at the launch of Mapping for Resilience: Turning Data into Decisions, a new program that aims to support geospatial data development in areas of need using OpenStreetMap.

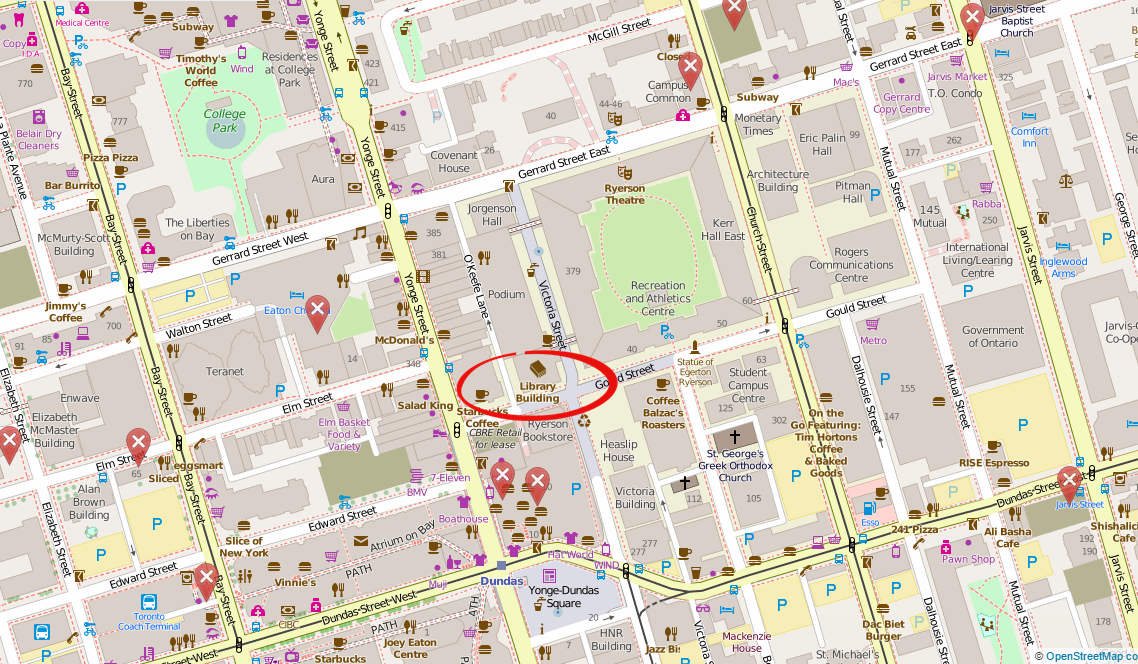

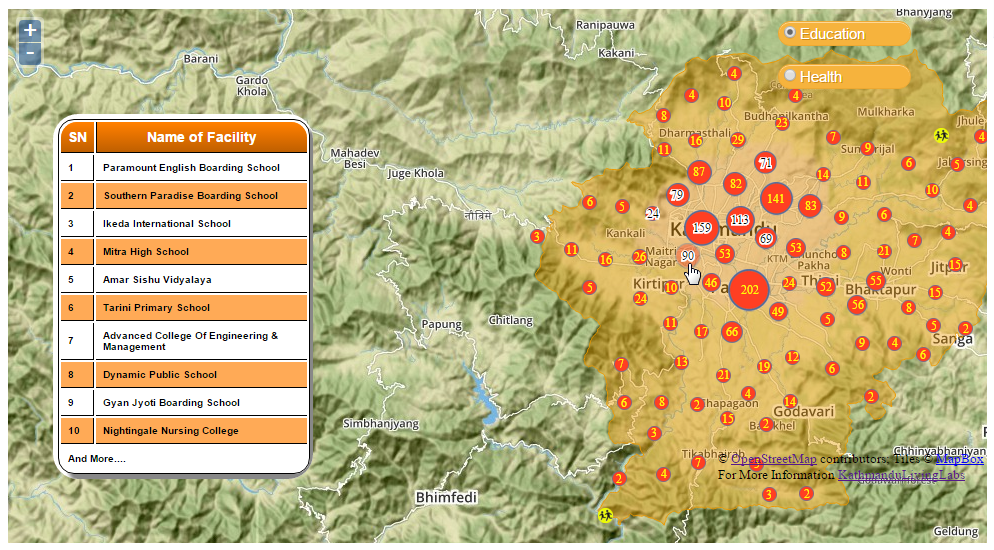

KLL’s Mapping Schools and Hospitals project

Mapping as civic engagement

The challenge that KLL has been addressing for several years now in Kathmandu is the lack of decent spatial data and maps for the region. The small team has been tackling the problem by collaborating with educational institutions in Nepal, training students how to map their local environment in OpenStreetMap. In 2013, for example, they went out into the field to collect exposure data at the individual building level for over 2,000 schools, colleges and universities, as well as 350 health facilities in Kathmandu Valley. They mapped this data on OpenStreetMap so that the information could be downloaded and used by government and other organizations developing risk assessments and plans.

For Budhathoki, the act of mapping is a mechanism for engaging citizens and building local knowledge and awareness. “I keep emphasizing this, but I can’t stress it enough. Mapping is not just about the final product — you know, the map itself. The act of mapping is important; it’s about engaging the community,” Budhathoki said. “In the process of conducting these activities, you are talking to people in the community, sensitizing them to the issues, preparing them in advance to think about it.”

Budhathoki notes that one of the most important reasons to have active, capable mapping communities on the ground in high-risk regions is so that they can build trust within their communities before disaster strikes. “KLL has been working with the government, working with organizations in the community, and with different aid organizations for several years,” Budhathoki said. “So when the earthquake hit, we not only had the local knowledge and the capacity so that we could open the situation room within 24 hours of the earthquake, but we also had the trust of all these organizations. In my experience, this element of trust is very important.”

Mobilizing the global community

Within 48 hours following the first earthquake, over 1,500 mappers around the world had responded to the call to support Nepal. Kathmandu Living Labs coordinated the effort together with HOT. This October, KLL posted a timeline capturing the milestones of their six-month journey since April.

As is typically the case on crowdsourced projects, while some contributors signed on only briefly, other mappers dedicated themselves to the cause. These core mappers, Budhathoki believes, tended to be those with a longer history on OSM and HOT projects, because they typically have a better understanding of the types of commitments and challenges involved.

“In principle, because OSM is a crowdsourcing geo platform, it is by definition designed to have a low barrier to entry,” Budhathoki explained. “Anyone should be able to begin mapping. That’s in principle. But in reality, there are tasks that require more knowledge. So for example, users with more OpenStreetMap experience handle validation tasks.

“GIS experts anywhere in the world should be able to adapt to the OpenStreetMap environment even if it is new for them. For GIS experts, OSM is a pretty simple tool, generally. They can contribute expertise that is useful, that contributes to quality of the information. But not everyone is comfortable in a crowdsourced environment.”

Where local meets global

Geothink co-applicant Claus Rinner, a professor and chair of Ryerson University’s Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, coordinated several Mapping for Nepal workshops in Toronto after the first quake struck. Rinner worked with a group of students with varying degrees of mapping experience as well as local GIS professionals to help map the affected areas. Following his experiences, he posted some reflections regarding the current slippery boundaries between traditional GIS and OpenStreetMap as a crowdsourced mapping platform — and highlighted the need for more formal education opportunities that incorporate OSM as a tool. More recently, Rinner noted that high school students have been expressing an interest in Ryerson’s mapping events for Nepal. “My main observation here is that OSM/HOT mapping is a type of community activity that uses the students’ study-related expertise,” Rinner said, “rather than being something that anyone could do.”

Budhathoki sees the work of the global OSM community as valuable on a number of levels, but also highlights the importance of local knowledge. “Virtual mappers without advanced knowledge can do fundamental tasks like mapping the road network,” Budhathoki said, “but then who can provide the name of the road? It’s the local community. And different countries categorize roads differently, so it is difficult to know what road is a highway, for example. You can’t just assume this based on the width of the road.

“So, local understanding is always going to be important — particularly in these situations, where the information is needed by humanitarian organizations and is being used on the ground right away.”

If you have any questions for Nama or the KLL team, you can reach them on Twitter here: @KTMLivingLabs

To get a quick sense of KLL and OSM’s work in Nepal since April, check out the Kathmandu Living Labs: Six-Months of Earthquake Response timeline.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Naomi Bloch, Geothink’s digital journalist, at naomi.bloch2@gmail.com.