This is a guest post from Geothink Student Tenille Brown, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa. She writes about her experiences as the first student in Geothink’s student exchange program.

By Tenille Brown

This past winter, I had the opportunity to be the inaugural ‘student visiting researcher’ through a new Geothink learning initiative focusing on student exchanges. Geothink is a Canada wide, multi-disciplinary grant. In practical terms this means there are university partners in disciplines as diverse as GIScience, urban planning, geography, communication and law. The visiting researcher programme has been established to give students the opportunity to see how other disciplines work. Through this programme, I — a graduate student in law at the University of Ottawa, and member of the Human Rights Research and Education Centre — found myself at a lab at UBC Okanagan. Professor Jon Corbett, a Geothink co-applicant, hosted me as I learnt about the lab, university and the city of Kelowna.

The SPICE Lab: Spatial Information for Community Mapping

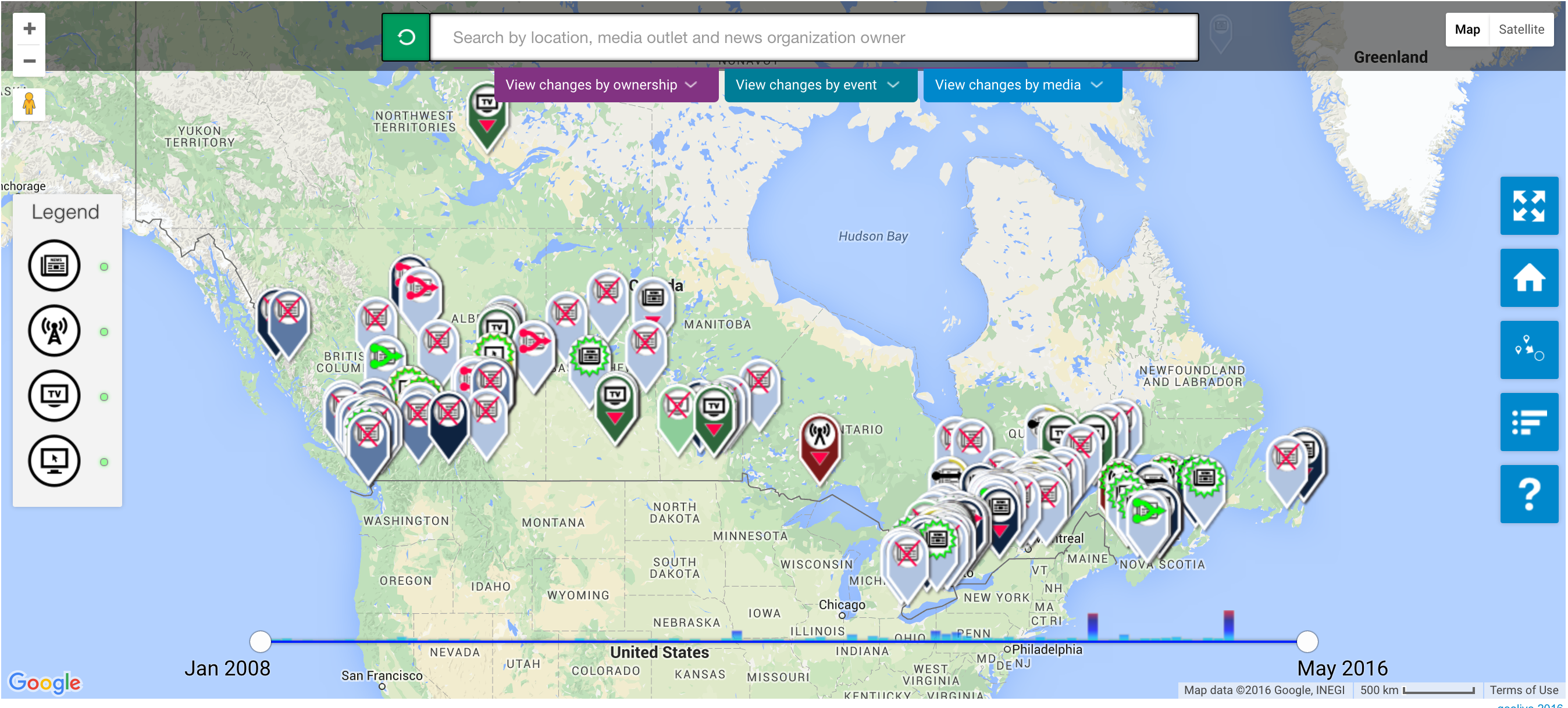

The SPICE Lab, Spatial Information for Community Mapping, is housed at the Centre for Social, Spatial and Economic Justice (CSSEJ) at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan campus. Led by Professor Corbett, the Centre looks at digital cartographic processes and tools that can be used by local communities to help express their relationship to, and knowledge of, their land and resources. A mapping tool that we have heard about at Geothink in the past, Geolive, was developed here. I was able to get an inside look at the mechanics of the Geolive system and learned about the process of collecting and coding the mapped information. As well as learning about the huge amount of resources that go into maintaining a system like Geolive (important information for the arm-chair geo-cartographers out there). I was also fortunate to get a preview of a recent collaboration between the Geolive team and Professor April Lindgren, an associate professor at the Ryerson School of Journalism and, academic director of the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre, and Geothink partner. Their project map titled, “The Local News Map: Tell us what is happening to local news in your community,” explores the issue of news poverty in Canada at a time of significant disruption in the news industry. The crowdsourced map will be available to the public so people can add information about the closure, launch or merger of local news outlets in their community. This collaboration between journalism and mapping was conceived at the 2015 Geothink AGM and will go live in the coming weeks (read more about it here).

Other activities I got involved in during my short stay in BC, included, observing community interviews carried out by Ailsa Beischer a student of Professor Corbett as she interviewed public health offices about food security (you can read about her work in a recent publication here). My visit coincided with a graduate programme lecture in Indigenous research methodology hosted by the En’owkin Centre, a First Nations community centre in the Okanagan valley. Of course, I got the chance to visit local Okanagan cultural sites.

So, what’s a law student to do in a geo-spatial lab?

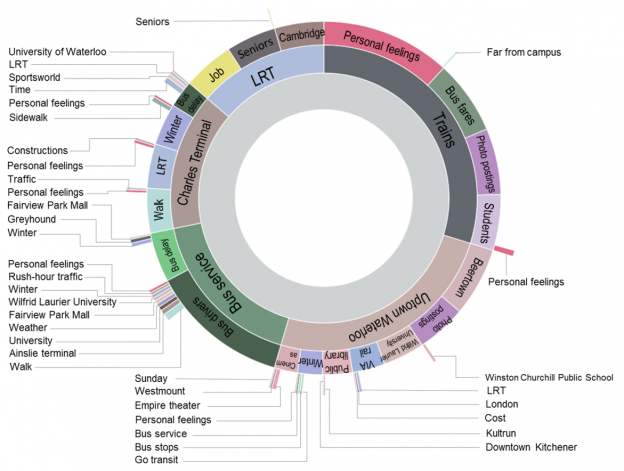

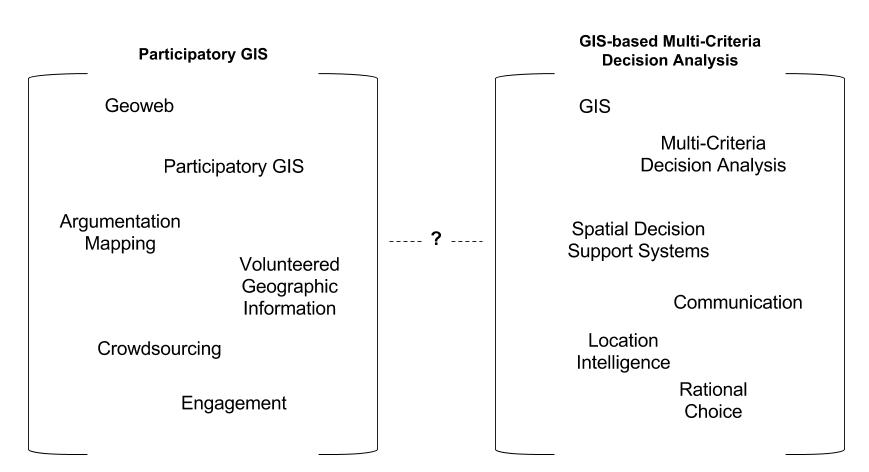

One of the core aims of Geothink is interdisciplinary research. This is a logical research objective given how integral multiple perspectives are to citizen-engagement; but from the often-siloed academy, surprisingly difficult to implement. My research is focused on property law and liability issues. I ask questions about ownership and legal adjudication of land and property, but from an interdisciplinary – law and geography – perspective. Adopting insights put into practice by the SpICE lab, I ask how cyber-cartography and the geoweb could be adopted to support individual and community experiences of property and land in ways beyond typical legal adjudication. In particular, the work of Geolive provides an opportunity to look at how community needs can be documented, raising the potential for critical insights about governance of land.

The visiting researcher position provided me with the opportunity to learn about the research processes of another discipline, in ways that I do not get to in my daily research schedule. In practical terms, I am deeply interested in both the utility and accuracy of information contained in the geoweb, and how programmers navigate the pressures of coding information to capture communities’ perspectives. These considerations – of accuracy and perspective – are of course long standing preoccupations of the legal field. But seeing the disciplinary similarities was apparent to me by visiting the SpICE lab and seeing the development process first hand. Having the opportunity to engage directly with the processes of researching and realizing digital-mapping projects, has been an impactful experience for my academic research, collaborations with Geothink researchers and personally.

Thank you to the Geothink team for sending me to UBC Okanagan. A huge thank you to Professor Corbett and his wonderful community of the CSSEJ for their support for my visit.

If you would like more information about my visit, or are a Geothink student thinking about going but still have questions, then please reach out to me.

Tenille E. Brown is a PhD Candidate under Professor Elizabeth F. Judge at the Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, where she is also a student member of the Human Rights Research and Education Centre. Tenille’s research is in the areas of legal geography, including property, spatial and citizen engagement. Tenille can be reached via email at, tenille.brown@uottawa.ca, and on Twitter, @TenilleEBrown