By Naomi Bloch

As an early warm-up to our November 23 Twitter chat — What does meaningful civic participation on the geoweb look like? — we asked Geothink Head Renee Sieber to share her perspective. Here are a few highlights.

More access, more communication

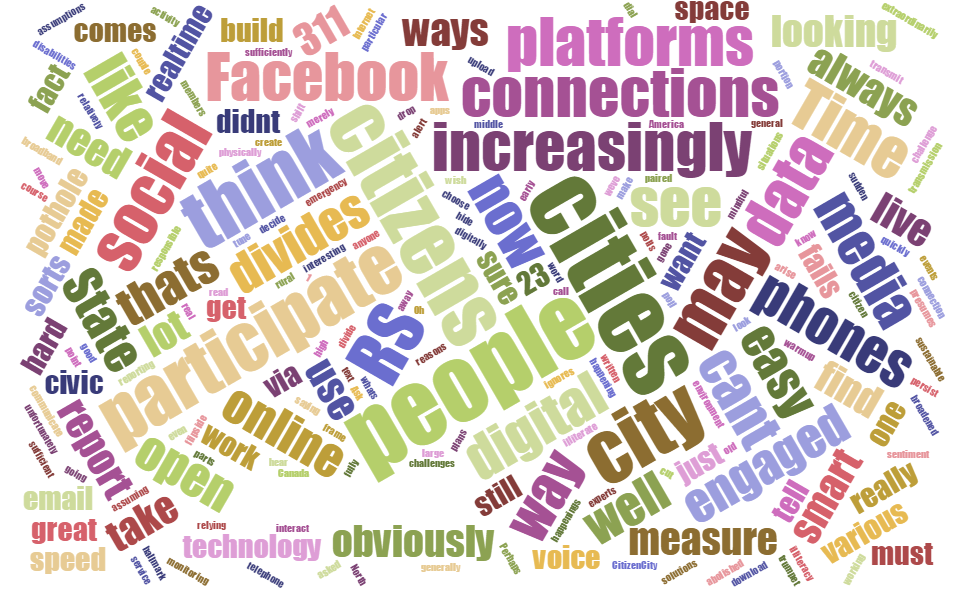

I think we’re in an environment where we’ve really broadened opportunities for citizens to participate through social media, through these various kinds of devices that we have, so I think it’s very exciting.

It’s an opportunity for citizens to be engaged when they don’t necessarily have the time to attend a meeting. So they can both watch city activities online through their own dashboards or they can communicate as issues arise. Perhaps cities may wish to create polls of online sentiment; they want to alert citizens of emergency situations or of interesting happenings in the city. —R.S.

Citizen–City connection

We can have citizens more fully engaged as members of the city in reporting, in monitoring events in real-time. People generally point to open 311 applications. Open 311 comes from an old telephone service where you could dial a short number, 311, and you could report a nuisance complaint. This has moved online. So the prototypical example is the pothole. You can report the pothole, you can report a missing street sign. This can be enormously helpful to cities because they have more real-time information for problems in the infrastructure. So that’s another kind of engagement. —R.S.

Hackathons

… Citizens can find new and unusual ways to use data that comes out of cities, in ways that cities had never thought about before. So it’s a very exciting way for people—particularly techies—to get into the mechanisms of governance and the mechanisms of government.

So I think that this is a great time to engage physically and digitally about what’s happening in your own cities. There are obviously challenges that are paired with that. —R.S.

Digital divides

One way that we frame technology is by saying that, “It’s so easy now that anyone can participate.” The flipside of that, unfortunately, is that if you cannot participate it’s your fault: “We made it easy for you, so if you don’t want to participate — or if you cannot or you didn’t choose to participate — in that particular poll, well, we can’t be responsible if we didn’t hear your voice.”

But that ignores all sorts of reasons that people cannot participate. The digital divide and digital inequities have not gone away, they merely shift and hide. So we can be relatively sure that a lot of people have e-mail, but in parts of rural Canada we can’t always be sure that people will have sustainable connections to the Internet, to broadband connections, to connections of a sufficient speed, to connections that persist over time as opposed to connections that drop out in the middle of an e-mail transmission or a call. That’s a real challenge if all of a sudden you decide to move a good portion of your citizen activity online; you cut out a large number of people.

We may say, “Oh great, we can build all these apps for smart phones.” Well, that of course presumes that people own smart phones, that people have data plans on smart phones, that people have sufficiently high speed connections on their phones so that they can transmit, upload and download data quite quickly. We can’t make those kinds of assumptions. —R.S.

Persistent social divides & inequities

You have to couple that with persistent digital divides and divides in general. Why are we assuming that illiteracy has been abolished in North America? We know that people still are illiterate. The hallmark of these technologies is that they’re increasingly relying on the written word. You have a phone, and you think we’re going to interact with the phone via voice. But increasingly people use their phones with text. Well, if you can’t read then you can’t participate. If you cannot see, you cannot participate. So we have all sorts of inequities based on disabilities.

So we have to be in tune to that, even as we trumpet the increased advantages and increased opportunities for people to participate. There will be people who will still find it extraordinarily challenging. Obviously people are working on solutions, but we have to be mindful of this in our rush to embracing digital engagement completely. —R.S.

Public space meets proprietary space

In terms of technologies and processes that are shaping these conversations, obviously social media and social networks have been incredibly important. We almost take for granted now that cities have Facebook pages—that departments in cities have Facebook pages. But that’s an odd concept when you step back and you think about it. That, (a) a city should have social media, and (b) that cities need to attach themselves to a specific proprietary network.

But the fact that cities are socially engaged via these platforms, that they actually spend the resources and see the need to have Facebook pages that are updated, that they have Twitter accounts, that they have YouTube channels, that they may be increasingly looking at applications like Meerkat and Periscope to allow for live streaming—that they may be incredibly concerned that applications like Meerkat and Periscope may be used to inadvertently live stream a conversation that they heretofore thought was private—I think these technologies have rapidly transformed the way that cities feel they must now be engaged with the public.

These technologies absolutely have technological implications and they have institutional implications as well. You have to have a person who updates your Facebook accounts. That takes some time to do. You may have to find someone who automates posting not only on Facebook, but to LinkedIn, to Twitter—that automation may require a systems administrator or coder employed by the city. The fact that cities now employ social media people, these are job titles that we did not see before: open data architects, CTO [chief technology officer] positions in cities. These are processes that have changed in cities.

—R.S.

Progress is not always made to measure

I think that in the future cities will increasingly start to grapple with what succeeds and fails. I think we’re in a publishing mode right now. I think that cities are doing all they can to keep up. So, the city has to publish as much data as it can on an open data platform. They have to engage in as many social media platforms as they can. I think they will increasingly need to take hard looks at what succeeds and what fails.

It is by no means easy to evaluate these platforms in terms of success and failure. What is an effective Facebook profile? How do you measure that? Do you measure it with “likes”? OK, that’s one very technical way of measuring it, but what does a “like” tell you about meaningful engagement? It might not tell you a lot.

So it’s easy to take the low-hanging fruit of measurements to determine whether platforms are successful or not. That may not be the right way to go. Cities are increasingly looking at analytics and predictive analytics to gauge the success of these various platforms and their engagement. But once again, that tends to based on what can easily be quantified. —R.S.

Humanizing the city

A lot of engagement between cities and citizens is much more longitudinal. It happens slowly over time. Cities and citizens build up trust. Distrust is easily gained, and very hard to get rid of.

I’ve been talking about cities as these homogeneous unions. But there are people in cities; there are citizens employed by cities, and often it is the ways that individuals in city governments reach out to individual citizens or groups of citizens, building up those linkages—using these technological platforms to heterogenize the city [that builds trust].

So, we begin to see the city and we see government as people engaging, just like you. They’re engaging with you, as opposed to being just The State (and you always must have this opinion about The State, or be in opposition to The State, or protest The State).

So [citizens can] use these technologies to sort of reach in, and stop looking at it as a monolith and more as a group of people who really are in city government because they wanted to work with citizens; they wanted to work on issues that were important and very close to the people who live in their cities. —R.S.

Join us for our #Geothink Twitter chat on civic participation on the geoweb: Monday, November 23 at 1 p.m. Eastern Time.