This is a guest post from Statistics Canada on their new initiative on crowdsourcing geospatial data

Statistics Canada’s crowdsourcing project offers an exciting new opportunity for the agency to collaborate with stakeholders and citizens to produce and share open data with the general public — that is to say, data that can be freely used and repurposed.

Data collection is evolving with technology; for example, paper-based and telephone surveys are increasingly replaced with online surveys. With an array of modern technologies that most Canadians can access, such as Web 2.0 and smartphones, a new mechanism for data sharing can be piloted through open data platforms that host online crowds of data contributors. This project provides insight into how Statistics Canada can adapt these modern technologies, particularly open source tools and platforms, to engage public and private stakeholders and citizens to participate in the production of official statistics.

For the pilot project, Statistics Canada’s goal is to collect quality crowdsourced data on buildings in Ottawa and Gatineau. The data include attributes such as each building’s coordinate location, address and type of use. This crowdsourced data can fill gaps in national datasets and produce valuable information for various Statistics Canada divisions.

On September 15, 2016, Statistics Canada launched a web page and communications campaign to inform and motivate the citizens of Ottawa and Gatineau to participate in the pilot project. This pilot project is governed and developed by Statistics Canada’s Crowdsourcing Steering Committee. Statistics Canada’s communications with the local OpenStreetMap (OSM) community and collaboration with stakeholders and municipalities have allowed the pilot project to succeed.

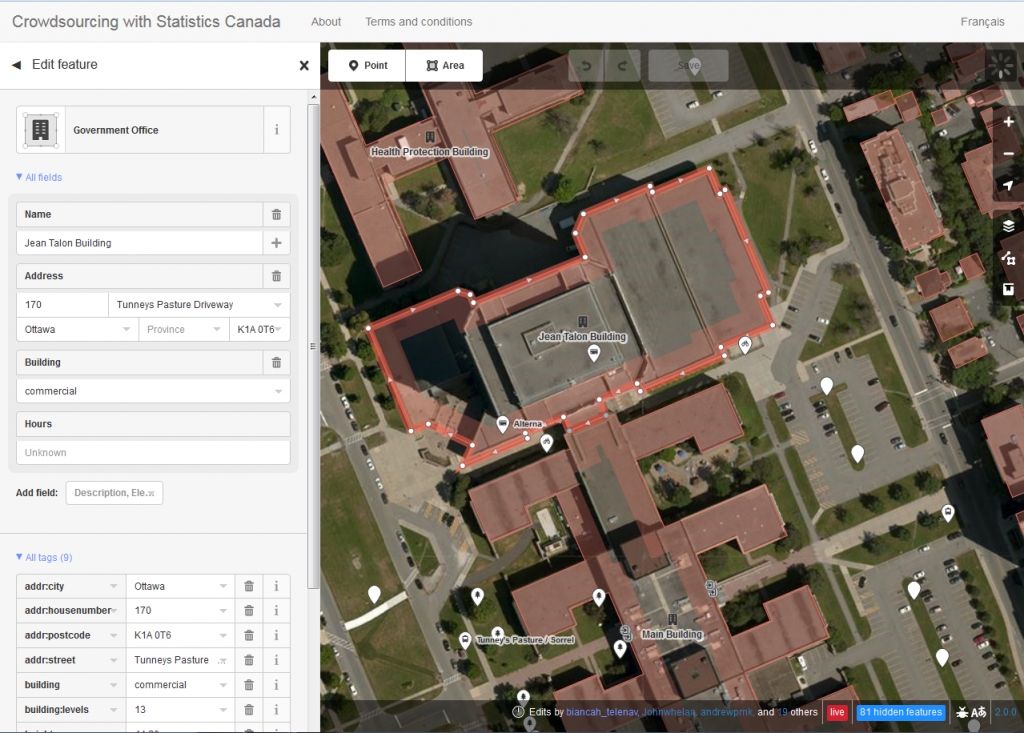

To crowdsource the data, the project uses OpenStreetMap, an open source platform that aims to map all features on the Earth’s surface through user-generated content. OSM allows anyone to contribute data and, under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL), anyone can freely use, disseminate and repurpose OSM data. In addition to the web page and campaign to encourage participation, Statistics Canada developed and deployed a customized version of OSM’s iD-Editor. This adapted tool allows participants to seamlessly add points of interest (POIs) and polygons on OSM. The platform includes instructions on how to sign up for OSM and how to edit, allowing anyone, whether tech-savvy or not, to contribute georeferenced data (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Snapshot of the customized version of OSM’s iD-Editor. Users can select a building or POI to see the attributes. Users can edit these attributes or they can create an entirely new point or area.

Statistics Canada has maintained communications with its stakeholders and participants through outreach, and has monitored contributions through dashboards. Outreach has taken place by communicating with the global and local OSM communities by using mailing lists and having local meetups, as well as by organizing webinars, presenting at local universities and participating in conferences associated with open data. Negotiation and collaboration with the City of Ottawa have also opened building footprints and addresses for contributors to add to the map.

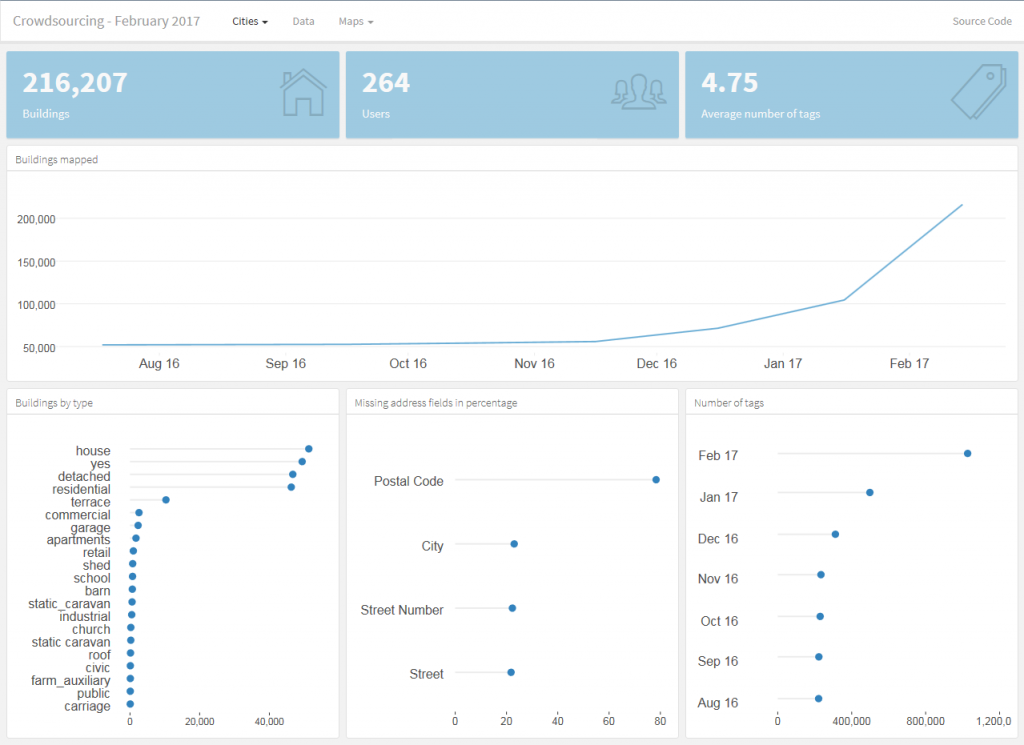

The project has been monitored using an open source dashboard developed by Statistics Canada. The dashboard provides a timeline (currently covering August 2016 to February 15, 2017) that specifies the number of buildings mapped, the number of users and the average number of tags contributed on OSM in each target city. Furthermore, it shows the amount of certain building types (e.g., house, residential, commercial) and the number of missing address fields by percentage (Figure 2). In general, the dashboard highlights the increased OSM contributions in Ottawa and Gatineau since the initiation of the project.

Figure 2. The open source dashboard monitors the production of data on OSM within the pilot project’s geographic scope of Ottawa and Gatineau. In the image above, both Ottawa and Gatineau have been selected. As seen in the top graph, buildings mapped in both cities have increased since the project’s initiation.

In the second year of the pilot project, Statistics Canada intends to develop a mobile app that will allow contributors to map on the go. Outreach will be maintained and, as more data are collected, quality assessments will be conducted. Success has been derived through collaborations, learning and sharing ideas, and developing user-friendly open source tools. As the project expands over time, Statistics Canada will uphold these values and approaches to ensure both an open and collaborative environment.

If you are interested in participating in the project, visit Statistics Canada’s Crowdsourcing website for a tutorial or to start mapping. Feel free to contact us at statcan.crowdsource.statcan@canada.ca to subscribe to a distribution list for periodic updates or to ask questions about the project.