By Drew Bush

Geothink’s Summer Institute may have concluded over a month ago, but, for those of you who missed it, we bring you three talks to remember. Run as part of Geothink’s five-year Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) partnership grant, the Institute aimed to provide undergraduate and graduate students from the partnership and beyond with knowledge and training in theoretical and practical aspects of crowdsourcing.

Each day of the institute alternated morning lectures, panel discussions and in-depth case studies on topics in crowdsourcing with afternoon work sessions where professors worked with student groups one-on-one on their proposal to meet a challenge posed by the City of Ottawa. See our first post on this here.

The lectures featured Geothink Head Renee Sieber, associate professor in McGill University’s Department of Geography and School of Environment; Robert Goodspeed, assistant professor of Urban Planning at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning; Daren Brabham, assistant professor in the University of Southern California Annenberg School of Journalistm and Communication; and Monica Stephens, assistant professor in the Department of Geography at State University of New York at Buffalo.

Below we present you with a rare opportunity to learn about crowdsourcing with our experts as they discuss important ideas and case studies. A short summary describes what each talk covers.

Geothoughts Talk One: In-Depth Case Studies in Crowdsourcing (1hr 3min)

Join Sieber and Brabham as they discuss two case studies that examine the actual application of crowdsourcing technologies and techniques to real-world situations. First Sieber describes the work of her Master’s Student Ana Brandusescu in applying crowdsourcing technologies to chronic community development issues in three places in Montreal, QC and Vancouver, BC. Next, Brabham discusses one of his first efforts to research the application of crowdsourcing technology to public transportation planning during a design contest he held for a bus stop at the University of Utah campus in Salt Lake City, UT.

Geothoughts Talk Two: A Deeper Dive into Crowdsourcing: Advanced Topics in Crowdsourcing and Civic Crowdfunding (1hr 8min)

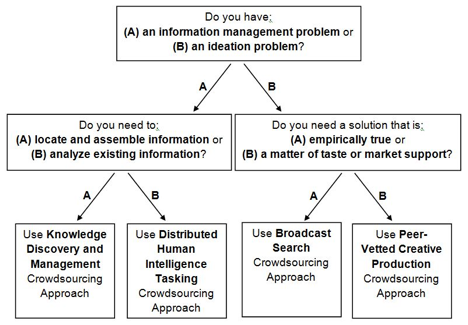

Goodspeed spends the morning covering three topics of inherent interest to anyone involved in crowdsourcing work. During this talk, he focuses in on three areas new to his own research including crowdfunding, formal crowdsourcing and the tool Ushahidi. Each of these topics helps prepare listeners for being a crowdsourcing professional.

Geothoughts Talk Three: Discussion on the Future of Crowdsourcing in the Public Sector (35 min)

Brabham and Goodspeed lead a discussion on where the future for crowdsourcing lies in the public sector. In particular, Goodspeed begins with an opening statement on how crowdsourcing can be used to help government agencies gain legitimacy by actually seeking input which can guide their actions. Brabham then challenges students to consider that crowdsourcing applications do fail and, even when they succeed, often can challenge whole professions that exist to collect the same data by other means.

If you have thoughts or questions about these podcasts, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.