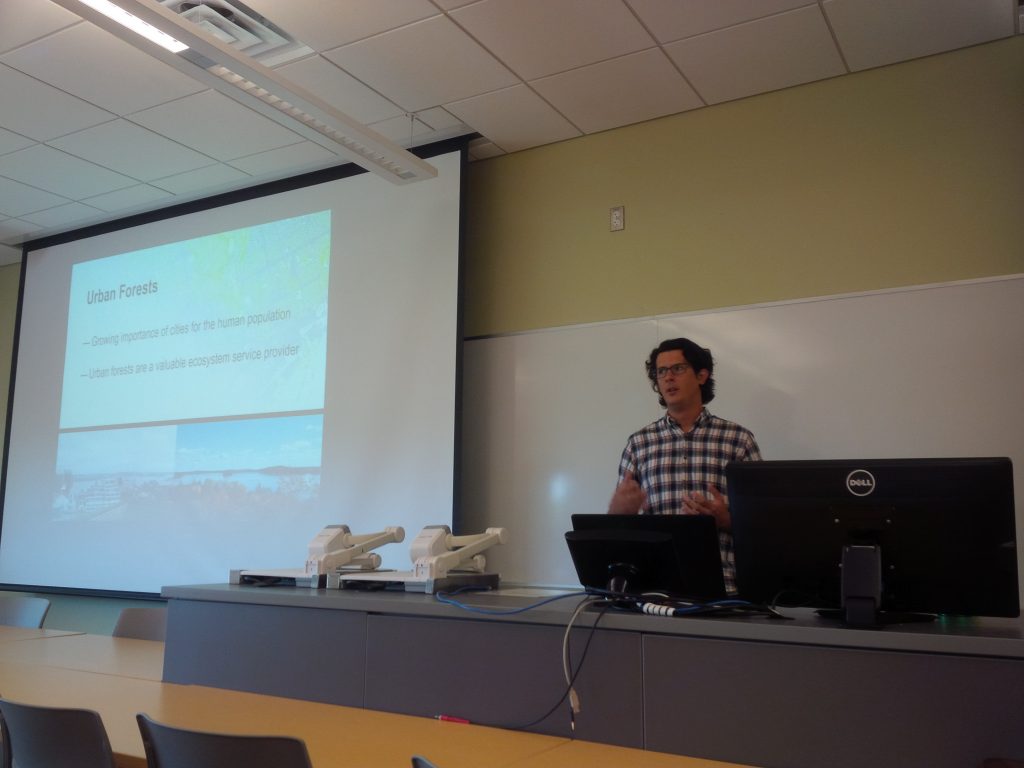

Images and text from sites like Flickr (the source of this image) provide geosocial data that University of Waterloo Associate Professor Robert Feick and his graduate students work to make more useful to planners and citizens.

By Drew Bush

A prevailing view of volunteered geographic information (VGI) is that large datasets exist equally across North American cities and spaces within them. Such data should therefore be readily available for planners wishing to use it to aid in decision-making. In a paper published last August in Cartography and Geographic Information Science, Geothink Co-Applicant Rob Feick put this idea to the test.

He and co-author Colin Robertson tracked Flickr data across 481 urban areas in the United States to determine what characteristics of a given city space correspond to the most plentiful data sets. This research allowed Feick, an associate professor in the University of Waterloo’s School of Planning, to determine how representative this type of user generated data are across and within cities.

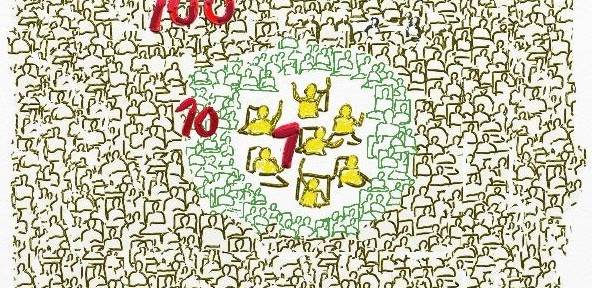

The paper (entitled Bumps and bruises in the digital skins of cities: Unevenly distributed user-generated content across U.S. urban areas) reports that coverage varies greatly between downtown cores and suburban spaces, as may be expected, but also that such patterns differ markedly between cities that appear similar in terms of size, function and other characteristics.

“Often it’s portrayed as if these large data resources are available everywhere for everyone and there aren’t any constraints,” he told Geothink.ca recently about this on-going research. Since these data sets are often repurposed to learn more about how people perceive places, this misconception can have clear implications for those working with such data sets, he added.

“Leaving aside all the other challenges with user generated data, can we take an approach that’s been piloted let’s say in Montreal and assume that’s it going to work as well in Hamilton, or Calgary, or Edmonton and so on?” he said. Due to variations in VGI coverage, tools developed in one local context may not produce the same results elsewhere in the same city or in other cities.

The actual types of data used in research like Feick’s can vary. Growing amounts of data from social media sites such as Flickr, Facebook, and Twitter, and transit or mobility applications developed by municipalities include geographic references. Feick and his graduate students work to transform such large datasets—which often include many irrelevant (and unruly) user comments or posts—into something that can be useful to citizens and city officials for planning and public engagement.

“My work tends to center on two themes within the overall Geothink project,” Feick said. “I have a longstanding interest in public engagement and participation from a GIS perspective—looking at how spatial data and tools condition and, hopefully, improve public dialogue. And the other broad area that I’m interested in is methods that help us to transform these new types of spatial data into information that is useful for governments and citizens.”

“That’s a pretty broad statement,” he added. “But in a community and local context, I’m interested in both understanding better the characteristics of these data sources, particularly data quality, as well as the methods we can develop to extract new types of information from large scale VGI resources.”

Applying this Research Approach to Canadian Municipalities

Much of Feick’s Geothink related research at University of Waterloo naturally involves work in the Canadian context of Kitchener, Waterloo, and the province of Ontario. He’s particularly proud of the work being done by his graduate students, Ashley Zhang and Maju Sadagopan. Both are undertaking projects that are illustrative of Feick’s above-mentioned two areas of research focus.

Many municipalities offer Web map interfaces that allow the public to place comments in areas of interest to them. Sadagopan’s work centres on providing a semi-automated approach for classifying these comments. In many cases, municipal staff have to read each comment and manually view where the comment was placed in order to interpret a citizen’s concerns.

Sadagopan is developing spatial database tools and rule-based logic that use keywords in comments as well as information about features (e.g. buildings, roads, etc.) near their locations to filter and classify hundreds of comments and identify issues and areas of common concern. This work is being piloted with the City of Kitchener using data from a recent planning study of the Iron Horse Trail that that runs throughout Kitchener and Waterloo.

Zhang’s work revolves around two projects that relate to light rail construction that is underway in the region of Waterloo. First, she is using topic modeling approaches to monitor less structured social media and filter data that may have relevance to local governments.

“She’s doing work that’s really focused on mining place-based and participation related information from geosocial media as well as other types of popular media, such as online newspapers and blogs, etc.,” Feick said. “She has developed tools that help to start to identify locales of concern and topics that over space and time vary in terms of their resonance with a community.”

“She’s moving towards the idea of changing public feedback and engagement from something that’s solely episodic and project related to something that could include also this idea of more continuous forms of monitoring,” he added.

To explore the data quality issues associated with VGI use in local governments, they are also working on a new project with Kitchener that will provide pedestrian routing services based on different types of mobility. The light rail project mentioned above has disrupted roadways and sidewalks with construction in the core area and will do so until the project is completed in 2017. Citizen feedback on the impacts of different barriers and temporary walking routes for people with different modes of mobility (e.g. use of wheelchairs, walkers, etc.) will be used to study how to gauge VGI quality and develop best practices for integrating public VGI into government data processes.

The work of Feick and his students provides important insight for the Geothink partnership on how VGI can be used to improve communication between cities and their citizens. Each of the above projects has improved service for citizens in Kitchener and Waterloo or enhanced the way in which these cities make and communicate decisions. Feick’s past projects and future research directions are similarly oriented toward practical, local applications.

Past Projects and Future Directions

Past projects Feick has completed with students include creation of a solar mapping tool for Toronto that showed homeowners how much money they might make from the provincial feed-in-tariff that pays for rooftop solar energy they provide to the grid. It used a model of solar radiation to determine the payoff from positioning panels on different parts of a homeowner’s roof.

Future research Feick has planned includes work on how to more effectively harness different sources of geosocial media given large data sizes and extraneous comments, further research into disparities in such data between and within cities, and a project with Geothink Co-Applicant Stéphane Roche to present spatial data quality and appropriate uses of open data in easy-to-understand visual formats.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.

Abstract of Paper mentioned in the above article:

Bumps and bruises in the digital skins of cities: Unevenly distributed user-generated content across U.S. urban areas

Abstract

As momentum and interest builds to leverage new user-generated forms of digital expression with geographical content, classical issues of data quality remain significant research challenges. In this paper we highlight the uneven textures of one form of user-generated data: geotagged photographs in U.S. urban centers as a case study into representativeness. We use generalized linear modeling to associate photograph distribution with underlying socioeconomic descriptors at the city-scale, and examine intra-city variation in relation to income inequality. We conclude with a detailed analysis of Dallas, Seattle, and New Orleans. Our findings add to the growing volume of evidence outlining uneven representativeness in user-generated data, and our approach contributes to the stock of methods available to investigate geographic variations in representativeness. We show that in addition to city-scale variables relating to distribution of user-generated content, variability remains at localized scales that demand an individual and contextual understanding of their form and nature. The findings demonstrate that careful analysis of representativeness at both macro and micro scales simultaneously can provide important insights into the processes giving rise to user-generated datasets and potentially shed light into their embedded biases and suitability as inputs to analysis.