Cornell University Lab of Ornithology’s E-Bird Web site allows citizen scientists to contribute data on birds for real scientific research as one novel application of crowdsourcing.

By Drew Bush

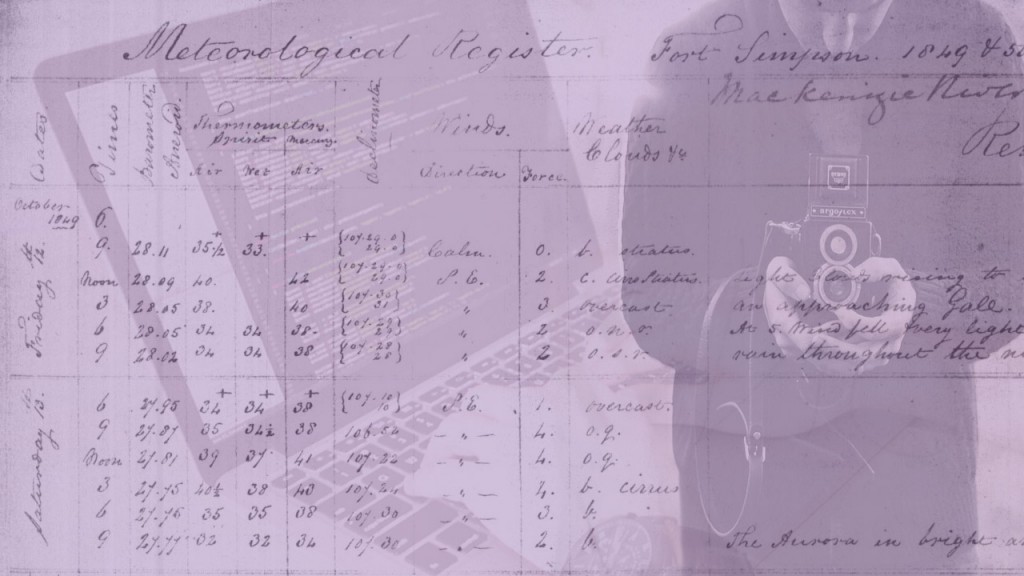

At Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology, scientists have long benefited from the legions of enthusiasts who find joy in observing and reporting the birds they see during their daily routines. In 2002, the lab worked with the United States National Audubon Society to launch eBird, an online database where scientists and amateur naturalists can submit real-time observations of the birds they see and their behavior. Since 2013, scientists have benefited from more than 100,000,000 observations and data for over 10,240 species in the program generated by more than 100,000 users.

Often hailed as an application of crowdsourcing that democratizes science by giving citizens the power to contribute, E-Bird is emblematic of a recent trend in applying crowdsourcing to problems outside the for-profit, business sectors where it began. In Canada, a new Community Fishers application allows citizen scientists to collect oceanographic data for Ocean Networks Canada and a number of Canadian cities use PlaceSpeak to collect public opinions on topics related to given locations. In the United States, this trend has led to the introduction of the Crowdsourcing and Citizen Science Act. The bill’s author, Senator Chris Coons of Delaware, wrote in a Wired article this past September that his bill makes explicit “that executive branch agencies, commissions, and all military branches have the explicit authority to make use of crowdsourcing and citizen science projects, utilizing the resourcefulness and innovation of the public to solve problems.”

Geothink researcher Daren Brabham is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California School for Communication and Journalism.

Geothink researcher Daren Brabham, an assistant professor at the University of Southern California School for Communication and Journalism, has long worked on research that supports this development. He is also widely credited as being the first to publish scholarly research that utilizes the word crowdsourcing. (Although he himself notes that one-time Wired editor Jeff Howe actually coined the term in a June 2006 issue where he wrote about Threadless.)

“I’ve got this kind of crazy idea for a citizen science kind of hub, you know call it for lack of a better term a [United States] citizen science corps for instance, or a North American citizen science corps,” Brabham said. “It would be a big program where all these scientific organizations could host—and also museums and researchers at state universities—could host their challenges that they want online communities to go do and solve these problems and gather scientific data in the community or whatever it might be. To post those in one single hub and find a way to gamify that where people can earn badges or level ups or even prizes for donors, or whatever it might be, to get people engaged in helping these organizations.”

Brabham believes crowdsourcing represents not only a tool to help scientists or the government do their work, but an opportunity to redefine what it means to provide service to one’s country—which in the past has been synonymous with military service. He envisions a future where if the United States National Aeronautics Administration (NASA) needs help analyzing water levels or categorizing stars by galaxy, they could involve thousands of citizen scientists in the project much like E-Bird does today.

Today’s trends in crowdsourcing mirror the evolution of his work. In particular, Brabham’s early work focused on applying crowdsourcing to uses in government, non-profits, and in public health. Many of these uses have since become common with, for example, the United States Office of Citizen Services and Innovative Technologies using DigitalGov to provide “information and services to the public anywhere and anytime.” In particular, one of its recent products, The Federal Community of Practice on Crowdsourcing and Citizen Science (CCS), works across the government to share lessons learned and develop best practices for designing, implementing, and evaluating crowdsourcing and citizen science initiatives.

Design Matters

Some of the key concerns for any crowdsourcing initiative, whether it be for urban planning, policy-making, or a for profit venture, is how to build a committed online community, sustain interest in it, and handle dissent amongst its users. Researchers on this subject seek to answer the question of what drives these communities to form and if design issues inhibit or accelerate this process.

For example, it’s difficult to know whether crowdsourced citizen science might succeed best if it involves primary school students in projects that count butterflies or instead utilizes iPhones to measure soil samples. It also helps to figure out why certain types of web-based platforms succeed at engaging communities while others have struggled. Brabham calls this type of assessment work “user-experience design,” which was a particular focus during Geothink’s 2015 Summer Institute.

In work he’s completed with other researchers, Brabham has found platforms that are easy to use, enjoyable, and have an intuitive interface have higher success rates. This may sound obvious but it’s more than just establishing a set of best practices for how all platforms should be designed. Instead, online sites must be organized according to the different tasks users are asked to complete or the different roles they might play.

For example, Brabham often talks about Threadless, a crowdsourced clothing and apparel site, and not just because his early involvement with it set him on his current research path after his now wife suggested he write a paper during his doctoral work applying this approach to sociocultural issues. In particular, he cites how Web sites like it give users a very clear idea of what audience it’s intended for, the activities the site allows users to undertake (shop, submit designs, or rate designs), and also includes a clear, user-friendly interface.

“I think when people are asked to contribute content or ideas or whatever it might be to a web site or organization in a crowdsourced arrangement, they really do care about how easy it is to convey their idea to you and figure out how it’s going to be used,” he said.

He points out that all too often researchers and critics focus on examining bad crowdsourcing initiatives rather than on what makes a given effort work. As crowdsourcing continues to be used in the public realm to help with citizen science efforts, paying attention to the details will become increasingly important. In particular, designers must provide users with multiple entry points, web sites with component parts organized based on tasks, and clear front pages that don’t overwhelm the average person.

A plethora of other issues surround both the implementation of crowdsourcing in public policy or for citizen science, and with its possible future uses. Brabham writes more about recent trends in the use of crowdsourcing in his recently published book: Crowdsourcing in the Public Sector. His earlier book, Crowdsourcing, is often cited for its importance in tracing crowdsourcing’s origins, future applications, and potential research paths.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.