Peter Johnson was one of four Geothink Co-Applicants who gave presentations on day two of the 2016 Geothink Summer Institute. Listen to their lectures here as podcasts.

By Drew Bush

Geothink’s Summer Institute may have concluded but, for those of you who missed it, we bring you four talks to remember. These lectures come from day two of the institute when four Geothink faculty members gave short talks on their different disciplinary approaches to evaluating open data.

The lectures feature Peter Johnson, an assistant professor at Waterloo University’s Department of Geography and Environmental Planning; Teresa Scassa, Canada Research Chair in Information Law at the University of Ottawa; Pamela Robinson, associate professor in Ryerson University’s School of Urban and Regional Planning; And, Geothink Head Renee Sieber, associate professor in McGill University’s Department of Geography and School of Environment.

Students at this year’s institute learned difficult lessons about applying actual open data to civic problems through group work and interactions with Toronto city officials, local organizations, and Geothink faculty. The last day of the institute culminated in a writing-skill incubator that gave participants the chance to practice communicating even the driest details of work with open data in a manner that grabs the attention of the public.

Held annually as part of a five-year Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) partnership grant, each year the Summer Institute devotes three days of hands-on learning to topics important to research taking place in the grant. This year, each day of the institute alternated lectures and panel discussions with work sessions where instructors mentored groups one-on-one about the many aspects of open data.

Below we present you with a rare opportunity to learn about open data with our experts as they discuss important disciplinary perspectives for evaluating the value of it. You can also subscribe to these Podcasts by finding them on iTunes.

Geothoughts Talk 4: Reflecting on the Success of Open Data: How Municipal Governments Evaluate Open Data Programs

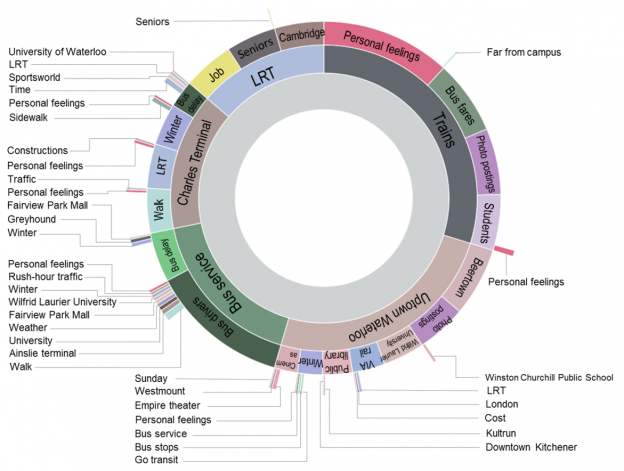

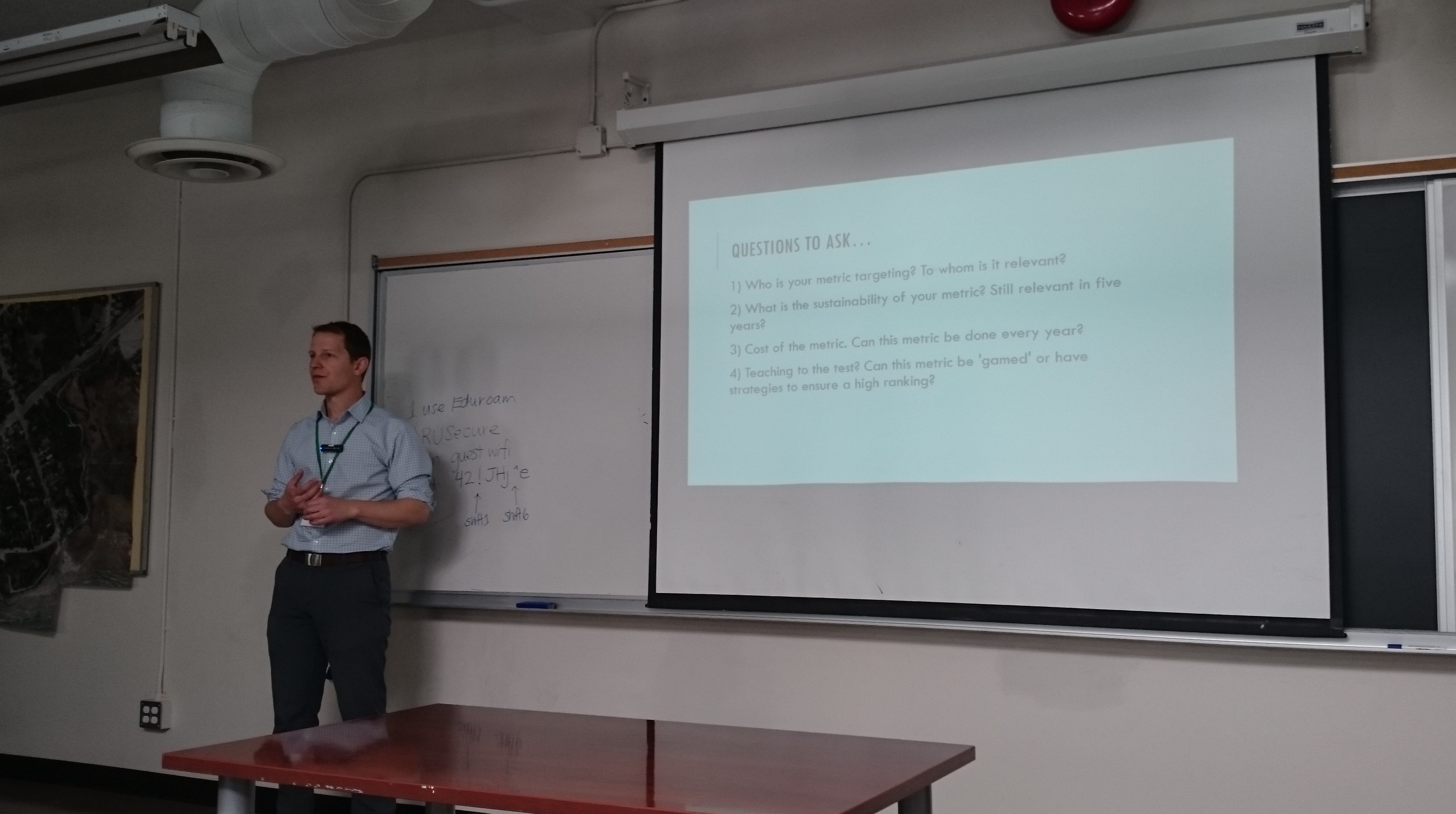

Join Peter Johnson as he kicks off day two of Geothink’s 2016 Summer Institute by inviting students to dream that they are civil servants at the City of Toronto when the city receives a hypothetical “F” rating for its open data catalogue. From this starting premise, Johnson’s lecture interrogates how outside agencies, academics, and organizations evaluate municipal open data programs. In particular, he discusses problems with current impact studies such as the Open Data 500 and what other current evaluation techniques look like.

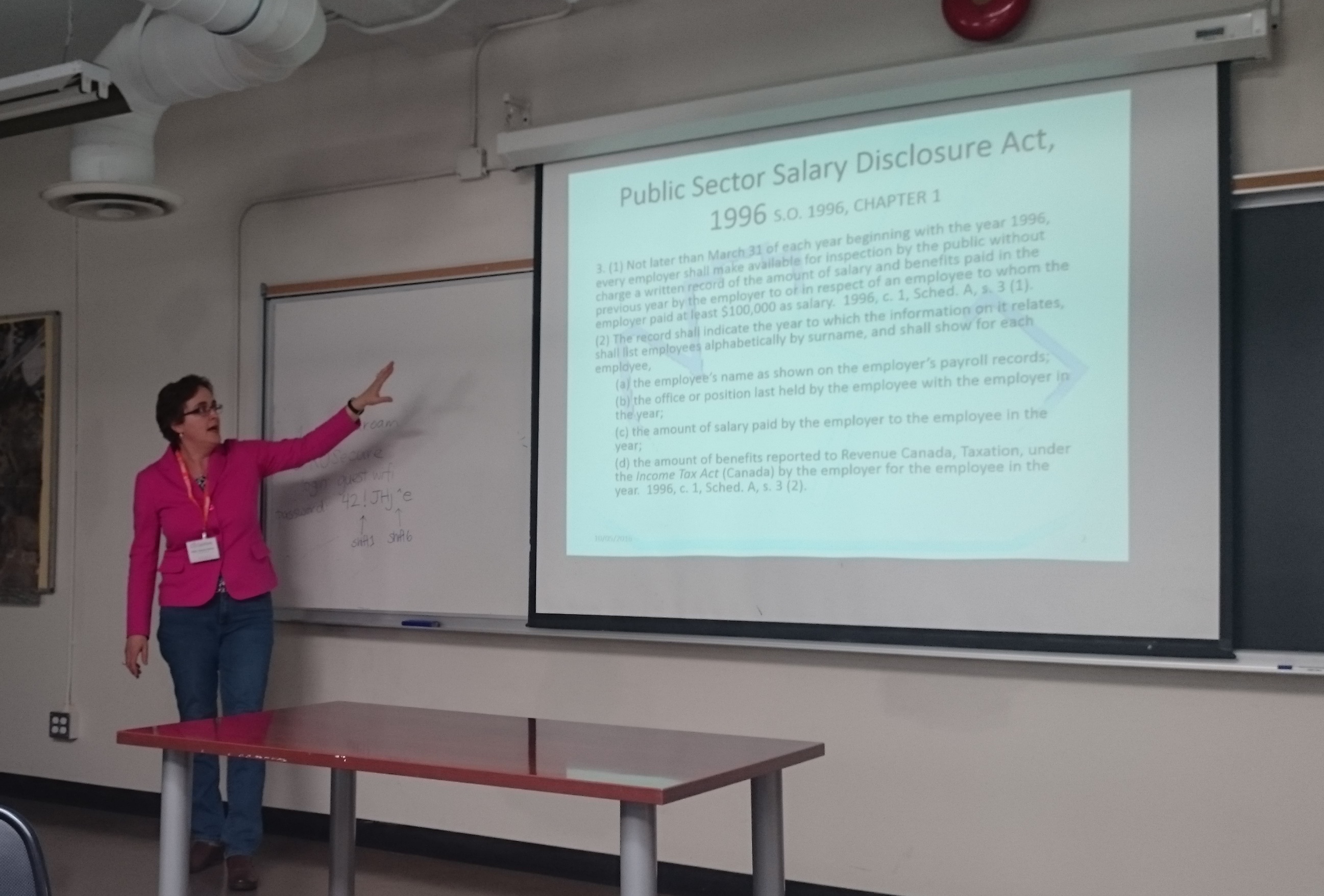

Geothoughts Talk 5: The Value of Open Data: A Legal Perspective

Teresa Scassa starts our fifth talk by discussing how those working in the discipline of law don’t usually participate in the evaluation of open data. While those in law don’t actually evaluate open data, however, legal statutes often are responsible for mandating such valuation, she argues. In particular, legal statutes often require specific types of data to be open. Furthermore, provisions in Canadian law such as the Open Courts Principle mean that many aspects of Canada’s legal system can be open-by-default.

Geothoughts Talk 6: Open Data: Questions and Techniques for Adding Civic Value

Pamela Robinson dispels the notion that open data derives value from economic benefits by instead discussing how such data can be used to fundamentally shift the relationship between civil society and institutions. She elaborates on this idea by noting that not all open data sets are created equal. Right now, she argues, the mixed ways in which open data is released can dramatically impact whether or not it’s useful to civic groups hoping to work with such data.

Geothoughts Talk 7: Measuring the Value of Open Data

In a talk that helps to summarize the previous three presenters, Renee Sieber discusses the different ways in which open data can be evaluated. She details many of the common quantitative metrics used—counting applications generated at a hackathon, the number of citizens engaged, or the economic output from a particular dataset—before discussing some qualitative indicators of the importance of a specific open data set. Some methods can likely capture certain aspects of open data better than others. She then poses a series of questions on how one can actually attach a value to the increased democracy or accountability gained by using open data.

If you have thoughts or questions about these podcasts, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca