By Drew Bush

Sometime early next week, Edmonton’s City Council will vote to endorse an Open City Initiative that will help cement the city’s status as a smart city alongside cities like Stokholm, Seattle and Vienna. This follows close on the heels of a 2010 decision by city leaders to be the first to launch an open data catalogue and the 2011 awarding of a $400,000 IBM Smart Cities Challenge award grant.

“Edmonton is aspiring to fulfill its role as a permanent global city, which means innovative, inclusive and engaged government,” said Yvonne Chen, a strategic planner for the city who has helped orchestrate the Open City Initiative. “So Open City acts as the umbrella that encompasses all the innovative open government work within the city of Edmonton.”

This work has included using advanced analysis of open data streams to enhance crime enforcement and prevention, an “open lab” to provide new products that improve citizen interactions with government, and interactive neighbourhood maps that will help Edmontonians locate and examine waste disposal services, recreational centres, transit information, and capitol projects.

For Chen, last week’s release of the Open City Initiative represents the culmination of years of work.

“My role throughout this entire release was I was helping with the public consultation sessions, I was analyzing information, and I was writing the Open City initiative documents as well as a lot of the policy itself,” she said.

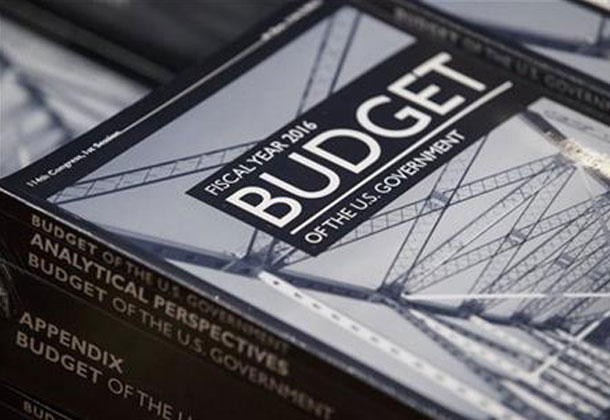

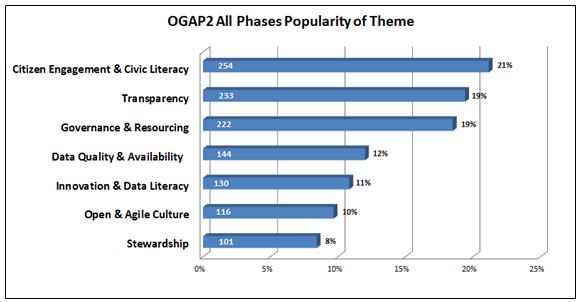

In fact, the document outlines city policy, action plans for specific initiatives, environmental scans (or reviews), and results from public consultations on city initiatives. More than 1,800 Edmontonians commented on the Initiative last October before it was revised and updated for the Council.

“The City of Edmonton’s Open City Initiative is a municipal perspective of the broader open government philosophy,” Chen adds. “It guides the development of innovative solutions in the effort to connect Edmontonians to city information, programs, services and any engagement opportunities.”

Like many provincial and federal open city policies, the document focuses on making Edmonton’s government more transparent, accountable and accessible. What sets Edmonton apart, Chen said, is a focus on including citizens in the design and delivery of city programs and services through deliberate consultations, presentations, public events and online citizen panels. In fact, more than 2,200 citizens are on just the panel asked questions by city officials as they design the Initiative’s infrastructure.

So what will it mean to live in one of North America’s smart cities? Edmonton is already beginning to provide free public Wi-Fi around the city, developing a not yet ready 311 application for two-way communication about city services, and working to fully integrate its electronic services across city departments.

“So one of the projects which has been reviewed very, very popularly is we have opened public Wi-Fi on the LRT stations,” Chen said of a project that includes plans for expanding the service to all train and tunnels. “A lot of commuters are utilizing the service and utilizing the free Wi-Fi provided by the city while waiting for their trains.”

What do you think about Edmonton’s Open City initiative? Let us know on twitter @geothinkca.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.