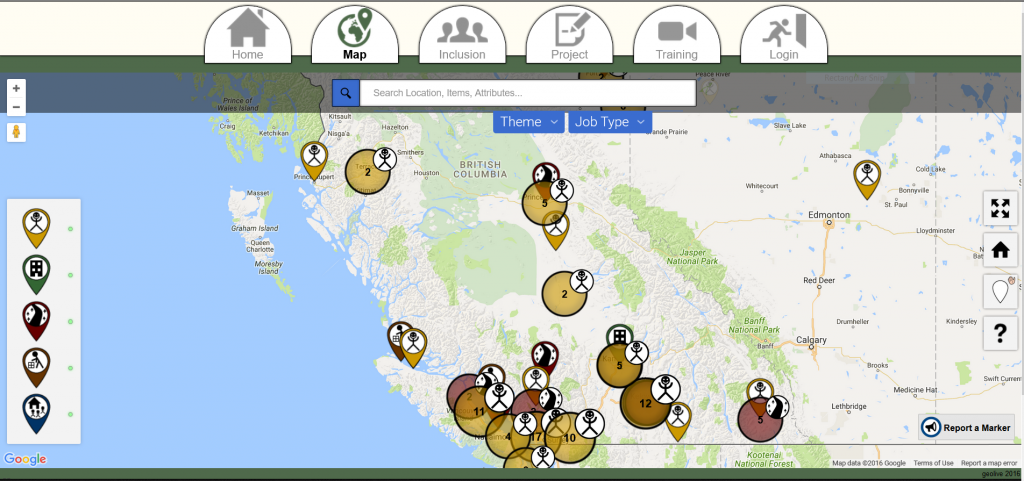

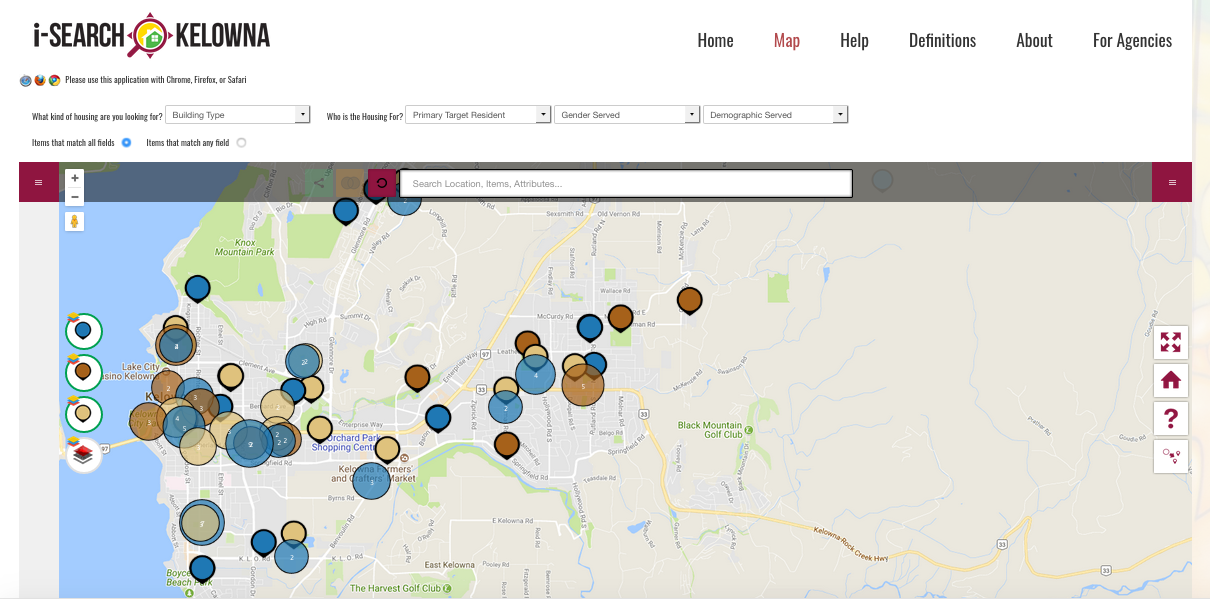

The iSearch Kelowna website is designed to assist individuals looking for low-income rentals, supportive housing or emergency shelters in the City of Kelowna.

By Drew Bush

One of the major challenge faced by anyone who finds themselves homeless involves finding shelter at places operated by a multitude of religious, goverment and nonprofit organizations. Thanks to the doctoral work of one Geothink student, that task just became a bit easier for those struggling with it in the City of Kelowna.

Shelley Cook, a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of British Columbia (UBC)-Okanagan, has worked with Geothink Co-Applicant Jon Corbett, an associate professor at UBC-Okanagan’s Department of Community, Culture and Global Studies, to design iSearch Kelowna. Via the app and website, individuals seeking low-income rentals, emergency shelter and drop-in services are able to search for live, user-specific information about resource availability within the city of Kelowna.

Shelley Cook, a University of British Columbia-Okanagan Ph.D. Candidate, developed the iSearch Kelowna site for her dissertation work.

“As we’ve moved out of phase one of our project, its morphing into another phase as it’s getting picked up as an important tool to inform this homelessness strategy, and people are running with it,” Cook said. In fact, this past summer the City of Kelowna decided to make iSearch Kelowna a central part of their strategy on homelessness. This highlighted Cook’s developing collaboration with the city on a project already supported by a team of reseachers, funders and partner organizations.

“It’s what we anticipated as what could happen and it’s lined up that way,” Cook said. “We’re maximising the benefit of the work that we’ve done, which is fantastic. It’s really in a strange way in its infancy, in terms of where it’s going to end up going, because it keeps evolving. So that’s been fantastic also.”

Cook’s work was recently recognized through Geothink’s first Dr. Alexander Aylett Scholarship in Urban Sustainability and Innovation (La Bourse Dr. Alex Aylett en Durabilité Urbaine et Innovation). The award was established in Aylett’s memory to provide vital support to graduate students sharing Aylett’s passion for, and commitment to, sustainable urban development.

Early feedback on iSearch Kelowna indicates that it is already providing users with a sense of ownership and advocacy over their own well-being and simplifying access to shelter information.

“It’s really about promoting empowerment, a greater sense of fairness and equity on the distribution of resources,” Cook said. “What we’ve done in terms of evaluation is directly talk to people who were formerly homeless or struggling with issues of maintaining adequate safe housing for themselves. That’s the one big thing they’ve talked about. And there’s lots of different elements around the interface that make it really usable and accessible.”

Speaking with Geothink during the Summer 2017 Summer Institute, Corbett added that issues of social and spatial justice motivate the research he and Cook have undertaken.

“There’s I think 84 different organizations that work on social justice related issues in and around the City of Kelowna,” Corbett said. “Which is kind of shocking because the population of Kelowna is only 185,000 people. So the fact that you’ve got 84 different organizations working is indicative of how serious the problem really is.”

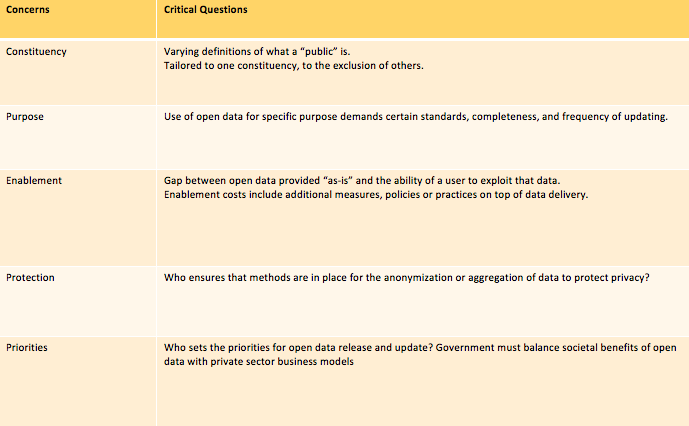

He noted that the city and funding organizations for these services had started to notice that each individual service providers was acting in isolation. As a result, there was no centralized place to find specific services across the city such as a hot meal or housing if you are over 55-years-old.

The initial tool Corbett envisioned was going to be aimed at service-providers using real-time data to help coordinate where to send homeless people for specific services. That evolved as Corbett and Cook began discussing the project with the City of Kelowna. It now includes portals for a variety of different types of users—including the homeless themselves.

“For us, it’s been a whole set of reasonable technical challenges,” Corbett added. “But we’ve also been dealing obiviously with this very, very important social question.”

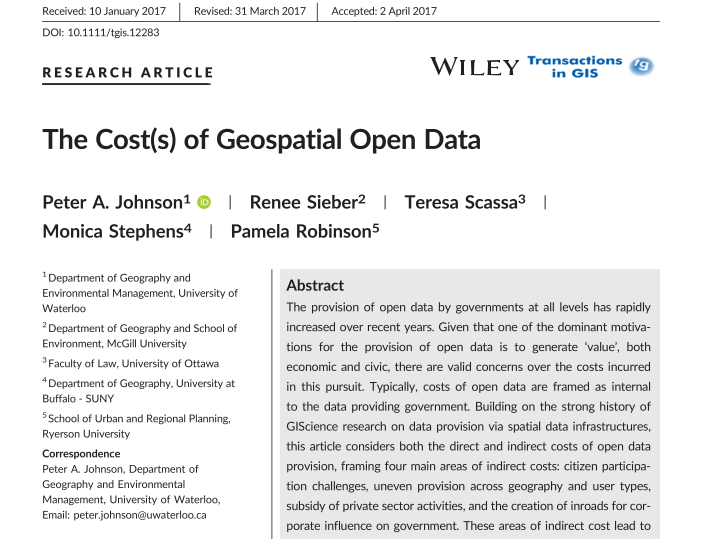

There are also endless applications for how the open data collected as a part of the project can make services more accessible and comprehensive for those in need. One worry has always been how to make what is a digital application accessible to a population that might not always have internet access.

“The main branch of the Kelowna library, a main point around Kelowna’s homeless community, has a dedicated monitor station during opening hours, is accessible for people to be able to search,” Cook said. “So it’s really about promoting service equity, and a greater sense of fairness and equity around the distribution of resources.”

“They now possess the knowledge,” she added of the homeless people using the site. “And what we know is they didn’t have the knowledge of all of [the city’s services]. So what that does is—the creating these forms of open data—opens up services to people and creates a more level playing field. Which is an incredibly powerful use of tools like this and was one thing that we weren’t necessarily anticipating.”

In the future, Cook plans to include more types of homeless services in the database and expand the site and offerings to other cities that have already expressed an interest in it.

“The final piece is an awareness raising and an ongoing partnership,” Cook said. “We’re doing presentations where communities have an interest in British Columbia and Alberta at this point. We can be of assistance in helping them develop a similar process and mentoring in that way.”

For Corbett and Cook, this means getting the project into the hands of city officials where it will live and exist for the community in perpetuity.

“So from the perspective of urban sustainability, we’re seeing municipalities, more so than in the past, getting involved with complex social issues like homelessness, and taking a lead role around these things,” Cook said. “Having a technological backbone that can help function not only to generate important information but to help people come together under a collective virtual umbrella. That’s a very powerful way to maximise and sustain existing community resources, and find innovative ways to create linkages and partnerships through tools and technology like iSearch Kelowna.”

###

If you have thoughts or questions about the article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.