By Sam Lumley

We’re excited to present our 15th episode of Geothoughts. You can also subscribe to this Podcast by finding it on iTunes.

In this episode, we take a look back over five years of fruitful Geothink research. We spoke to Geothink Head Renee Sieber, Co-Applicants Rob Fieck, Daniel Paré and Stéphane Roche, and Geothink students Rachel Bloom and Edgar Baculi about their most memorable experiences with the grant.

Thanks for tuning in. And we hope you subscribe with us at Geothoughts on iTunes. A transcript of this original audio podcast follows.

TRANSCRIPT OF AUDIO PODCAST

Welcome to Geothoughts. I’m Sam Lumley.

[Geothink.ca theme music]

“The Geothink grant that was funded by the social science and humanities research council of Canada is coming to an end. We have done great work in terms of creating new theories, new frameworks, new applications, new data sets new collaborations.”

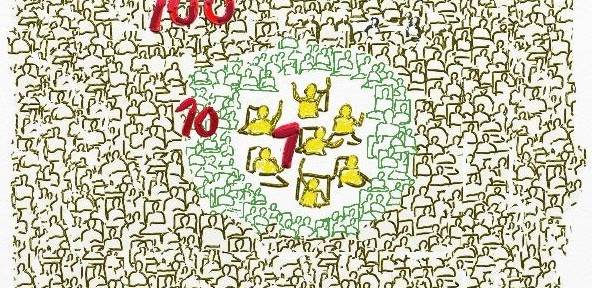

That was Geothink Head Renee Sieber, an associate professor at McGill University’s Department of Geography and School of Environment. Funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Geothink partnership grant has involved 26 researchers and 30 partners, while also training more than 100 students. As the grant wraps up, we’ve been hearing from our researchers and students as they reflect on their involvement in the grant over the past five years.

We started off by speaking to former Geothink student Rachel Bloom about her most memorable experiences with the grant.

“I was the lead of Geothink’s Open Data Standards project when I was a student at McGill University. The most memorable Geothink experience would have to be designing a survey that I delivered to open data publishers at cities in north america about open-data standards. It’s memorable because it was a really challenging process due to my research topic being so new. And it also helped me develop my skills as a researcher for the future.”

The Geothink grant has brought together researchers from many different backgrounds and from different parts of the world. It was this point that Geothink co-applicant Rob Feick, an associate professor in Waterloo University’s School of Planning, emphasised while talking about the influence of Geothink on his own work.

“My research has really benefited from my work with Geothink in a few ways, one of which is Geothink is really a multi disciplinary network. It’s a network of people that span disciplines from geography, law, planning and a host of others. And having these different types of expertise around the table has really helped ground my research.”

“It’s also very applied work we’re working with local regional governments on problems that matter to people, both problems that matter to people right now and those that people are seeing both in the research community and in applied context, coming down the pipe in future years. So one of the ways, just using special data quality as of those areas that a number of us have been looking at and that that I have really benefited from in my exposure in Geothink, is understanding that it is far less of a technical matter and it’s a combination of technical and a social and governance matter, and we’re starting to understand that something that we thought was relatively simple, of spatial data quality, is much more complex.”

This interdisciplinary approach was also highlighted by Sieber, as being essential to exploring how interactions between citizens and government are mediated by technology.

“It’s been marvelous in terms of the interdisciplinary of bringing together geographers lawyers, people in the private sector, people in government to work on issues of what’s happening to the conversations between citizens and cities. And on how can we make sure the technology is not an impediment, but actually enhances that conversation”

Working alongside people from different academic fields can help to offer a broader perspective on the big issues facing citizens and governments. It also led some Geothink researchers to shift their own own research interests. This was the case for Geothink Co-Applicant Stéphane Roche, an associate professor in University Laval’s Department of Geomatics, who talked about his focus moving from the technical to the ethical over the course of the grant.

“My main interest within Geothink was more about social inclusion within a smart city context, spatial justice and ethics, which was quite far from what I was supposed to do at the beginning. So in my case, the move was quite big. Geothink is as a network different sectors, different disciplines, different expertise, and working on these issues around the relationship between spatial and social justice, cities and technology. And that that was really remarkable. I really enjoyed and appreciated the the dynamism and the motivation of our group of students, some of them coming from law, some others from engineering some from social science. And it was really rich in term of interaction.”

Throughout the grant new partnerships and opportunities have emerged, and co-applicant Daniel Paré, an associate professor in the University of Ottawa’s Department of Communication and School of Information Studies, highlighted his new collaborations with the Open Government Partnership.

“My involvement with Geothink has influenced my research in so much as it has opened the door towards getting to work with OGP partnership. So based on my Geothink work in open data and open government, that’s transformed, if you will, into the role with the OGP. Where I’m responsible for overseeing assessments of the implementation of Ontario’s Open Data Action Plan.”

We went on to ask Paré about his most memorable experiences as part of the grant.

“I think the most memorable experience has been working with the great team that was put together, and that includes our great team of students that are brought together every year in terms of the student based meetings and such. So for me that’s always been a highlight of the team actually getting together physically and meeting over a period of three to four days. That’s been key; those sessions always been so rich on multiple levels.”

Opportunities for collaboration and exchange were facilitated by the four Geothink summer institutes. Many collaborators and partners emphasised how helpful it was to bring researchers, partners and students together under one roof. Feick pointed to 2015 Summer Institute held at McGill University as being his most memorable moment.

“I’ve had a lot of memorable moments in this in this project over the years, but I think the one that sticks with me the most was at a summer institute that we had for the Geothink students here at waterloo. The summer institutes are opportunities where students from a variety of different universities could come together and work on an applied problem and learn about a particular aspect of geospatial information and its interfacing with society.”

“Students in this particular summer institute had the task of developing an application. We had teams of students that hadn’t met before that came together over the course of a week and put together some really fantastic applications. And these applications, I think, spurred a lot of their own research that they were going to continue on with, but also was really interesting to see how again the different perspectives that the students brought, along with those people that were assisting them through the SI, actually came to fruition.”

The summer institutes also stood out to former Geothink student Edgar Baculi, now a graduate researcher in Ryerson’s Department of Geography.

“We have all these disciplines and I remember benefing greatly from talking to the economics student, sociologist, communication and journalism students on the topic open data and it opened my mind to the idea of, if we’re talking about open data it’s not just going to be the GIS people who are going to benefit or the academics, it’s going to be the sociology students, it’s going to be a journalist from the Toronto Star, it’s going to be all these people who need to understand what open-data is from their perspective and from other perspectives.”

“So, I would say, Geothink was very important in letting me know the inside from other perspectives. And as for networking, that’s a lot of disciplines to go through, and we were all from across canada, and I think actually a few of us were from the States, if I remember correctly, so it was a great networking experience. Many of them are still friends of mine on twitter and LinkedIn, so, great experience.”

The five-year Geothink Partnership Grant may be coming to its conclusion, but the research and its applications will continue. We asked Sieber what lay in store for Geothink’s research themes, the community the partnership helped to foster and the grant’s continuing work.

“We have transformed, I’m happy to say, the lives of over 100 students. I’d like to think that we transformed the lives of many people in the public sector and the private sector across canada. I know it has certainly transformed my life. It has transformed the life of the researchers involved in this project.”

“So while this grant ends, that doesn’t mean that Geothink as a concept, and a research trajectory has ended. Many of our apps will live on beyond us. Certainly our research and our own research trajectories have been changed as a result, so that work’s going to go on even after the grant ends. And, of course, we’re also looking for new grants to pursue this research!”

[Geothink.ca theme music]

[Voice over: Geothoughts are brought to you by Geothink.ca supported by generous funding from Canada’s Social Sciences and Research Council and generous donations from our grant partners.]

###

If you have thoughts or questions about this podcast, get in touch with Sam Lumley, Geothink’s digital journalist, at sam.lumley@mail.mcgill.ca.