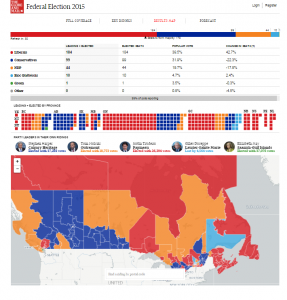

- Globe & Mail’s federal election results map.

- Maclean’s magazine’s March 26, 2015 feature (http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/mapped-10-years-of-unprecedented-change-in-canadas-cities/)

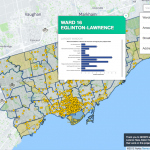

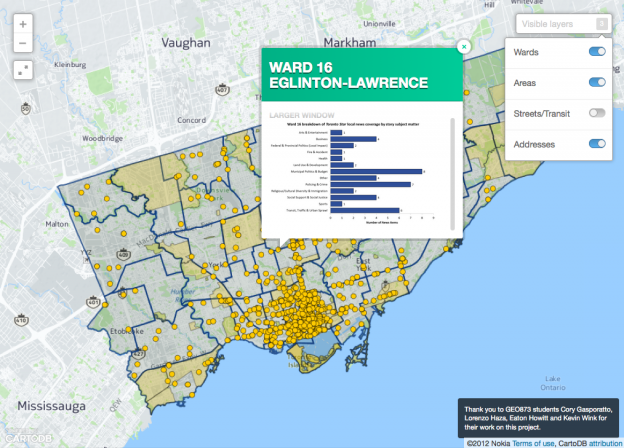

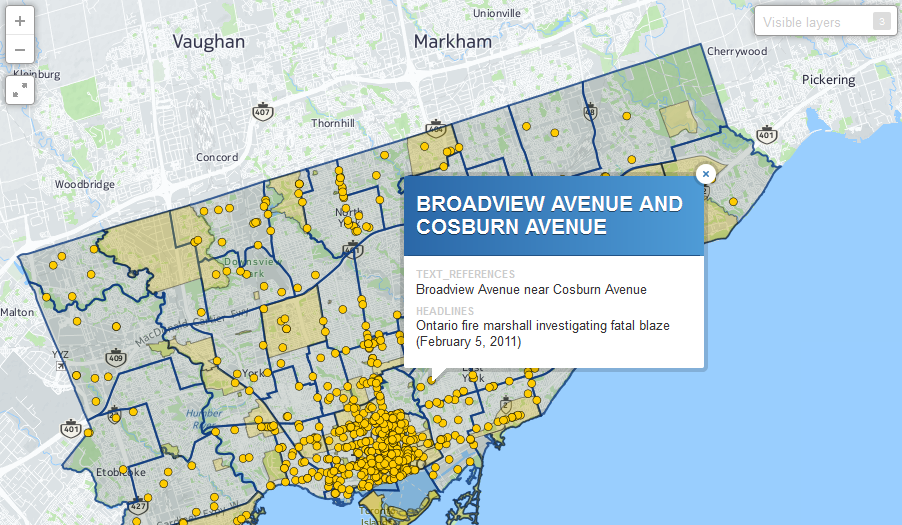

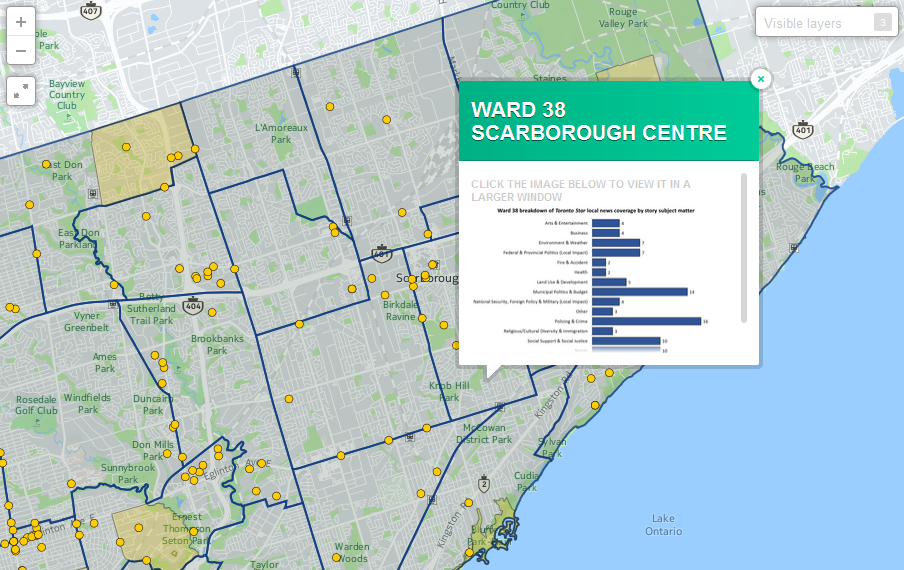

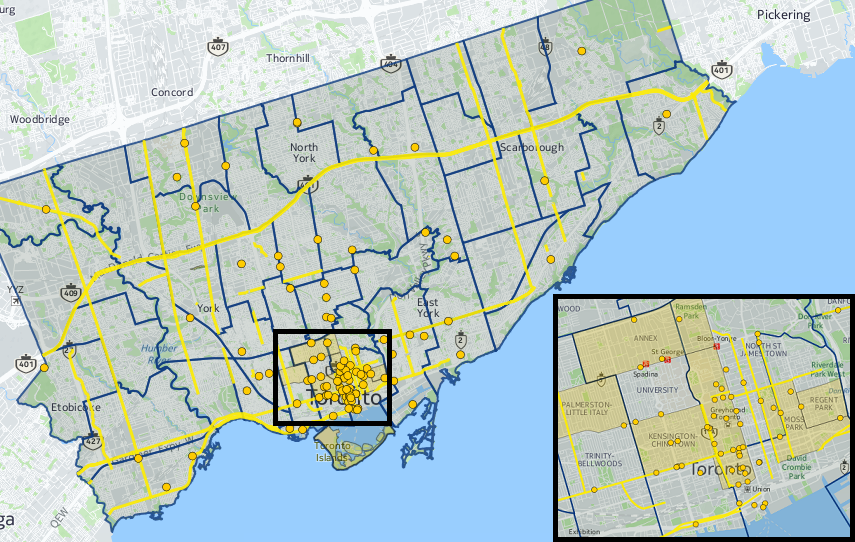

- Ryerson’s Local News Research Project (LNRP) examines local news coverage patterns.

- The Vancouver Sun regularly publishes geodata-informed local content (http://www.vancouversun.com/news/metro-mapped/index.html)

- The Globe and Mail uses commercial realty data for its biannual depiction of Toronto’s housing market.

By Naomi Bloch

The rise of more accessible geospatial web tools along with expanding sources of open data have fostered a potent—if somewhat techno-utopian—civic vision. For those immersed in understanding this new digital landscape, one question often surfaces: who’s truly putting these resources to use?

The most reliable answer is perhaps an obvious one. “Journalists are making huge use of mapping and geodata for storytelling, for the visualization of stories, and for investigative reporting purposes,” said April Lindgren, an associate professor at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism and founding director of the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre, a Geothink partner organization.

As a scholar, Lindgren’s own research employs data mapping techniques to examine the geography of news coverage and the role of Canadian media in society. “Maps have actually been quite a powerful tool for us to explore patterns of local news and understand how it works. It opened up a whole new way of getting at and understanding the data because we were able to visualize it.

“Before that, it was the old problem of columns and reams of numbers” Lindgren said. “But being able to map it allowed us to show geographically, yes, most of the news coverage is focused on downtown Toronto. So why is that? And what are the implications of not doing much coverage in other areas of the city? And furthermore, we mapped the types of topics. So what does it mean when most of the news that they publish about certain areas is crime coverage? What does that do in terms of the geographic stereotyping?”

Computer-assisted reporting revisited

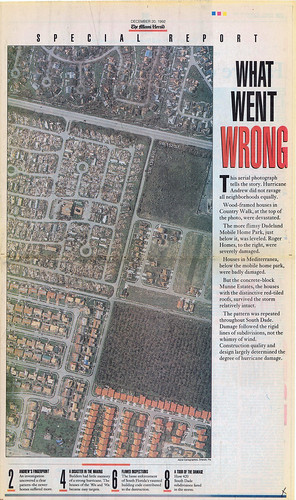

Lindgren notes that the use of mapping and data analysis for actual journalistic purposes is not a new phenomenon. Over twenty years ago, in 1993, Miami Herald research editor Steve Doig won a Pulitzer Prize for his investigative coverage of Hurricane Andrew’s aftermath in Florida. The year prior, Doig and his colleagues spent several intensive months processing and evaluating two data sets—one that helped to map out property damage caused by the hurricane and another documenting wind speeds at different locations and times throughout the storm. “They noticed from using mapping that the damage was much more extensive in certain areas than in others, and then they started trying to figure out why that was, because weather-wise it was the same storm,” Lindgren explained.

“What Went Wrong > Miami Herald, December 20, 1992 > Page 1” (originally published Dec. 20, 1992). Flickr photo by Daniel X. O’Neil, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Further investigation unveiled that several different developers had been responsible for real estate construction in different regions. “And it led them to a conclusion and a very powerful piece of journalism showing that it had to do with the building standards of the different developers,” said Lindgren. “So that was one of the early uses of mapping and data journalism, showing what a useful tool it could be.”

As researchers raise questions about the skills and motivations that enable citizen engagement with open data and geospatial technologies, journalism schools are increasingly recognizing the need to integrate a formal understanding of data journalism into the curriculum.

At the 2014 Geothink Annual General Meeting, Lindgren met a fellow researcher with complementary interests—Marcy Burchfield, executive director of the Toronto-based Neptis Foundation. The aim of Neptis has been to apply the unique capabilities of mapping and spatial analysis to help decision makers and the public understand regional issues in the Greater Toronto Area. The Geothink encounter led to the development of a Neptis-led geodata workshop for senior-level students enrolled in Ryerson’s journalism school, exposing students to some statistics basics as well as the various challenges of working with spatial data to develop meaningful stories.

“Getting the data into a usable form, I think, is probably the biggest challenge technically for journalists,” said Lindgren. “Although the skills are rapidly increasing and we’re training our students to do that.”

At Ryerson, undergraduates are required to take an introductory digital journalism course that critically engages with social media and citizen journalism along with new forms of multimedia and alternative storytelling methods. A separate “visualizing facts” elective course aims to provide hands-on experience with various data visualization techniques including mapping, while reinforcing numeracy skills (something that, historically, journalists have not been known for).

Data’s fit for purpose?

CBC News’s crowdsourced, interactive “Pledge to Vote” map, part of their 2015 Canada Votes coverage.

In recent years Canadian data journalists have garnered international attention both for their creative uses of geodata and their involvement in the push for open access to government information. “One of the big problems is the availability of data,” Lindgren said. “What’s available? How good is it? How hard do you have to fight for it? Is it really available through an open data source or do you have to go through Freedom of Information to get it?”

While increasingly media outlets are exploring the possibilities of engaging the public to create crowdsourced content by volunteering their geodata, the data sets that journalists tend to be interested in—ideally, data that can support rich, informative stories relevant to public interest—are not typically collected with the journalist in mind. In particular, government data sources have often been generated to support internal administrative needs, not to address transparency and accountability concerns per se. Data input decisions may not be documented, and agencies may “silently” post-process the information before distributing it to journalists or the greater public. This makes the process of learning how to clean up inconsistent, non-standardized data developed for a very different audience a particularly important skill for journalists to acquire. Only then can a journalist build an understanding of the data’s patterns and the stories they can support.

“You’re only as good as your data,” Lindgren emphasized. “In some ways the act of journalism allows you to test the data and see how good it is. Because the data may be telling you one thing, but then when you go out on the ground and you start interviewing and looking around you may find that what you’re seeing and hearing doesn’t seem to match what the data is telling you.

“So right away, as a journalist you’re going to be suspicious of that. And there are two places where this could be wrong. Either you’re talking to the wrong people or you’re not talking to a broad enough range of people—or there might be something wrong with the data.”

Verifying data accuracy is a time-honoured tradition

Lindgren shared the example of a colleague who was investigating the issue of slum landlords. The reporter asked the municipality to provide data on property standards complaints. Upon receiving and eventually mapping the data, the reporter and his colleagues made a surprising discovery. “They noticed that there was a section of the city that didn’t have any complaints. They thought that was odd, because they knew that there were a lot of rental areas and low-income areas there, with people living in somewhat vulnerable housing situations.”

Ultimately, the dissonance between the story on the ground and the story in the data led the reporter to go back to the city seeking further verification, and the nature of the problem soon revealed itself. It seems that a summer student had been in charge of aggregating and disseminating the data to the journalists when the information was requested, and that student had overlooked one section of the city.

While this particular story reflects human error during the communication phase rather than the data collection phase, Lindgren points out that the strong journalistic traditions of seeking verification and being suspicious of information sources puts the media in a unique position to evaluate data’s quality. “Verification is a fundamental element of journalism. That’s what we do that’s different from anybody who is just commenting out there online. The main issue is: is it verifiable, and what’s the public interest? That’s the starting point.”

Where public and private interests intersect

What constitutes “public interest” is a conversation that still needs to happen. The push for open data and the fact that personal information is increasingly accessible online has led parties both within and beyond government to raise concerns about how to strike the balance between privacy and transparency—and what the right balance may be. Data sets often contain personal or identifying information. Cleansing the data of that information is not straightforward. Even when data appear on the surface anonymized, there are ever increasing opportunities to combine and process seemingly unrelated data sets in ways that can identify individuals and compromise personal information. As Geothink co-applicant researcher Teresa Scassa has addressed more than once in her work, this is not a theoretical problem but a reality that is already occurring.

Lindgren, however, said she does not see data journalism as giving rise to new types of ethical concerns for the media. “Obviously, a balance has to be struck. But the reality is that oftentimes the data is very generalized. It really depends on what the issue is and what the information is.

“The whole privacy issue is really a red flag, a lot of times, for journalists, because it can be used by governments as a pretext for not releasing information that governments just don’t want the public to know. The two reasons they don’t release information is privacy and violating commercial interests, and then the third reason is political consideration, but they can’t couch it in those terms.”

In terms of how journalists themselves strike that balance, Lindgren said this must be assessed on a case by case basis. “Basically, our job is invading people’s space, quite often. So we have to—and we do—make those judgment calls every day. The data is just another layer of that, or another area where we’d have to think about it and have those discussions.

“What it comes down to is you’re weighing, what’s the public interest in this information? There’s no hard and fast rule. It depends on what the information is.”

If you have any questions for April, reach her on Twitter here: @aprilatryersonIf you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Naomi Bloch, Geothink’s digital journalist, at naomi.bloch2@gmail.com.