The 2017 Geothink Summer Institute on smart cities will convene May 25 to May 27 on McGill University’s downtown campus in Montreal, Quebec. (Image courtesy of http://jeannesauve.org)

By Drew Bush

As 22 Geothink students pack their bags and get ready for this year’s three-day 2017 Summer Institute “Smart Cities: Toward a Just City” their host city (and Geothink partner) will be preparing as well. This year’s Summer Institute will kick-off May 25 to May 27 in Montreal as celebrations for the municipalities 375th anniversary shift into high gear.

The timing couldn’t be more serendipitous: Strategic plans overseen by Montreal’s Smart and Digital City Office call for making the municipality a world renowned leader among smart cities by 2017. This year’s Summer Institute will bring together an interdisciplinary group of students and faculty—from law, geography, planning and more—to learn about issues facing smart cities and meet with key leaders in Montreal’s work toward becoming a leader in this field.

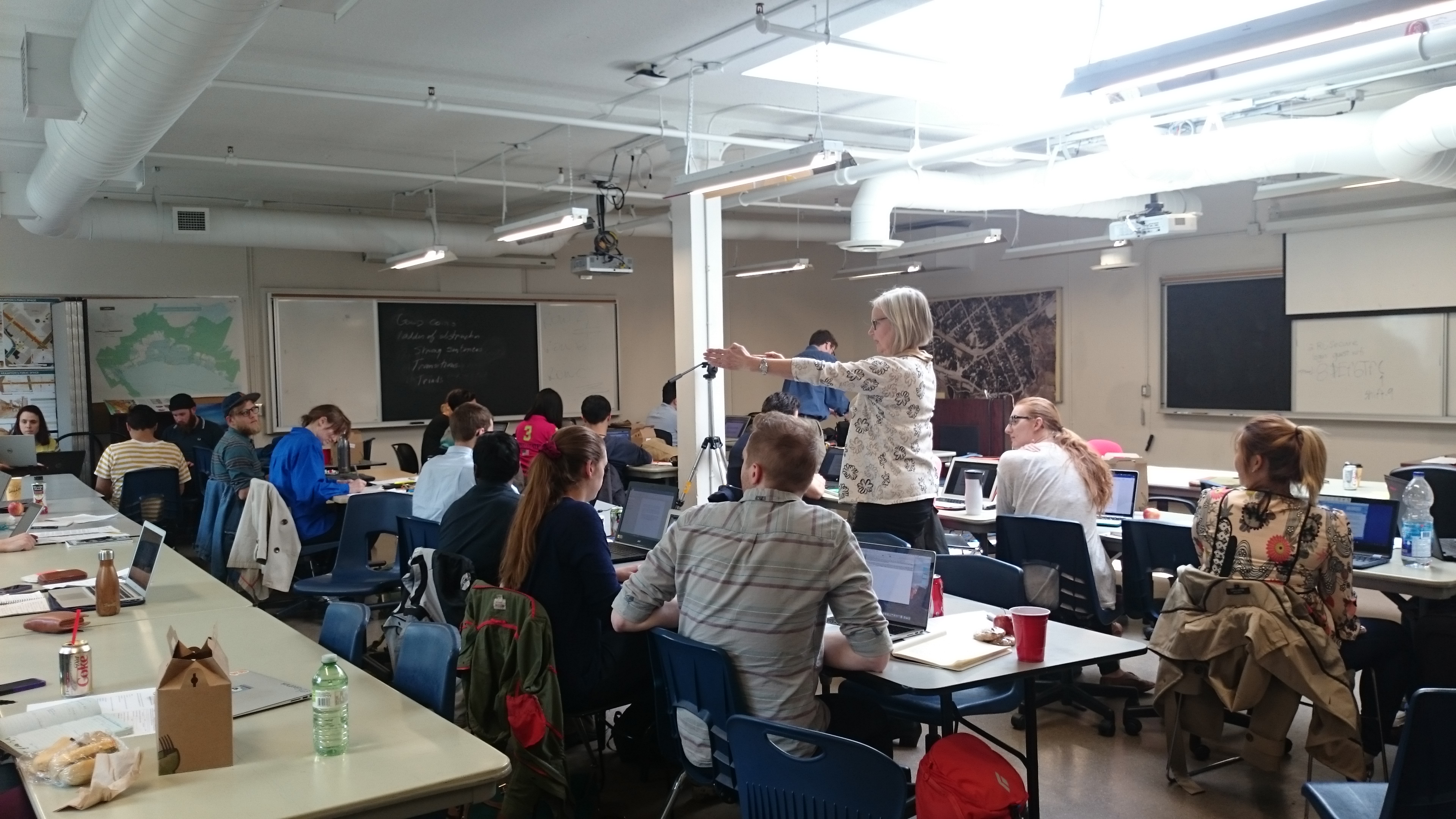

“It’s essential that students appreciate the ways in which smart technology can lead to fairer and just city-citizen interactions,” said Geothink Head Renee Sieber, associate professor in McGill University’s Department of Geography and School of Environment. “Students in this Summer Institute will learn about accessibility in smart cities, the promotion of social justice in this new environment and the integration of technology into city processes.”

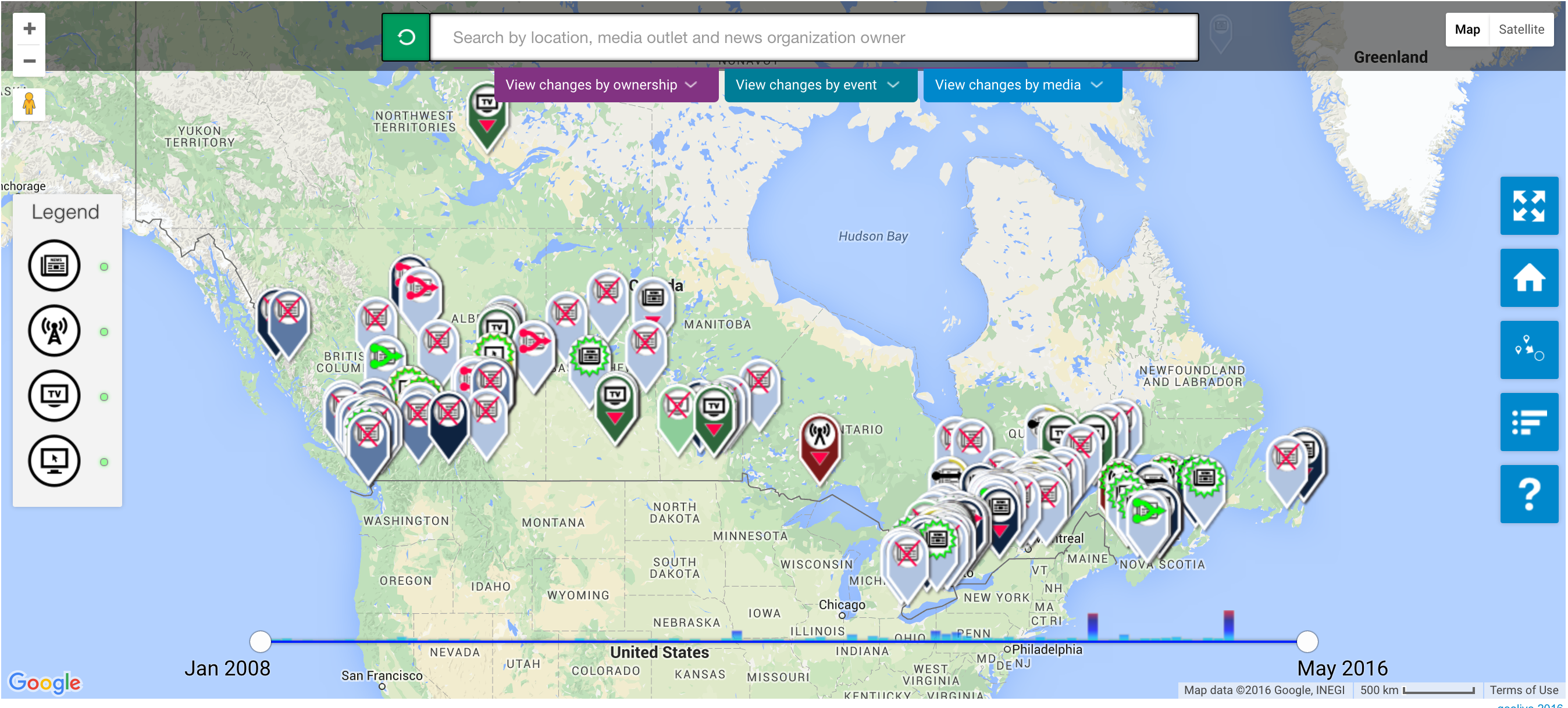

Each of the three days of the Summer Institute will combine workshops, panel discussions and hands-on learning modules that will culminate in a competition judged by city officials. The goal of the competition will be for student groups to develop novel uses for Montreal’s open data to improve accessibility in the city.

The first day of the Institute will introduce the idea of smart cities during a panel discussion with Sieber and Geothink Co-Applicants Jon Corbett, associate professor in University of British Columbia at Okanagan’s Department of Geography; Stéphane Roche, associate professor in University Laval’s Department of Geomatics; Pamela Robinson, associate professor in Ryerson University’s School of Urban and Regional Planning; Rob Feick, associate professor in Waterloo University’s School of Planning; and Teresa Scassa, Canada Research Chair in University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law. Later that day, students will be introduced to the problem they are trying to solve and hear from Montreal City Council Chairman, M. Harout Chitilian.

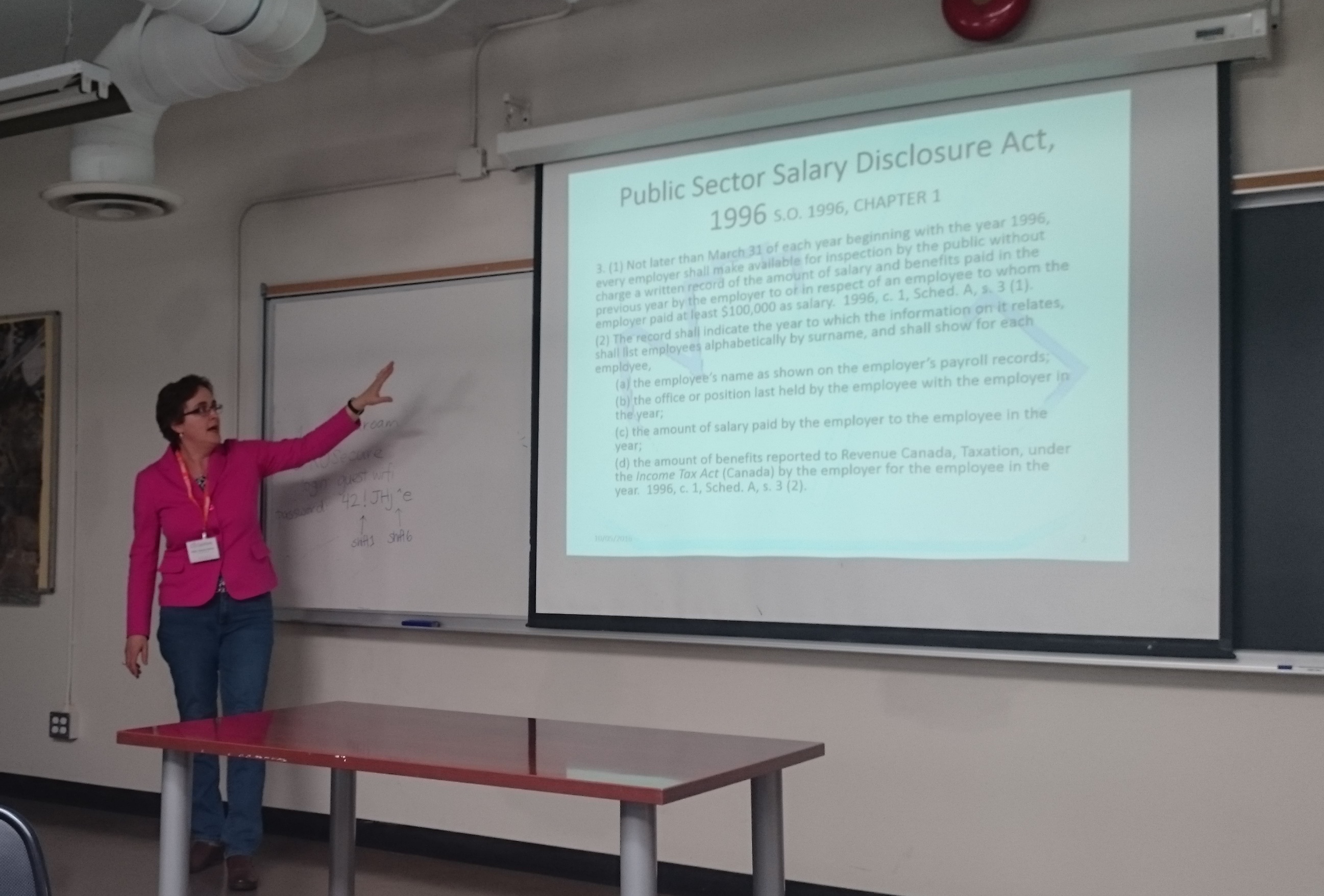

On day two, students will learn about legal issues relating to smart cities from Scassa, ethical considerations from Roche and social justice issues from Corbett. Multiple sessions throughout the day will also be devoted to group work on projects.

Finally, on day three, two separate talks will be headlined by Jean-Noé Landry, executive director of Open North, and Xavier Peich, a co-founder of Smarthalo. After time to work on project presentations, the day will conclude with the competition.

“Students will be exposed to smart city issues from a variety of perspectives, including government, non-profits, local tech entrepreneurs, planners and, of course, academia,” Geothink Student Coordinator Suthee Sangiambutt said. “This is going to be a fun event. Student attendees are from all sorts of disciplines and there will be a great opportunity to learn new skills and perspectives around smart city problems.”

The summer institute is hosted by Geothink, a five-year partnership grant awarded by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) in 2012. The partnership includes researchers in different institutions across Canada, as well as partners in Canadian municipal governments, non-profits and the private sector. The expertise of the group is wide-ranging and includes aspects of social sciences as well as humanities such as geography, GIS/geospatial analysis, urban planning, communications, and law.

“We’re really fortunate to have such an interdisciplinary group of students who can unpack the term ‘smart’ from multiple angles to better understand both the challenges and opportunities that cities face today,” Geothink Project Manager Sonja Solomun said.

If you have thoughts or questions about the article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s guest digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.