Our first podcast delves deeper into how Canada’s Action Plan for Open Government 2.0 has failed to fully engage civil society groups.

By Drew Bush

We’re very excited to present you with our first Geothink.ca Podcast in our series, Geothoughts. You can also subscribe to this Podcast by finding it on iTunes.

Our first podcast delves deeper into the opinions of Tracey Lauriault, a researcher at The Programmable City project who specializes in open data and open government in Canada. We explore how Canada’s Action Plan for Open Government 2.0 has failed to fully engage civil society groups and take you inside her work with front-line groups like the Canadian Council on Social Development and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

Thanks for tuning in. And we hope you subscribe with us at Geothoughts on iTunes. A transcript of this original audio podcast follows.

TRANSCRIPT OF AUDIO PODCAST

Last week Geothink.ca brought you a story about the lack of civil society engagement with Canada’s Action Plan for Open Government 2.0. This week we delve deeper to find out what exactly is missing.

[Geothink.ca theme music]

Welcome to Geothoughts. I’m Drew Bush.

“For me that’s the disappointment. There wasn’t outreach to civil society as I know it. And that’s the civil society organizations that are actually involved in policy formulation or evidence-informed policy on whatever—a variety of issues from transportation planning to anti-poverty to mining extraction.”

That’s the opinion of a researcher at The Programmable City project who specializes in open data and open government in Canada.

“So my name is Tracey Lauriault and I’m working on a European Research Council funded project called The Programmable City. It’s based here at the National University of Ireland in the village of Maynooth at the National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis.”

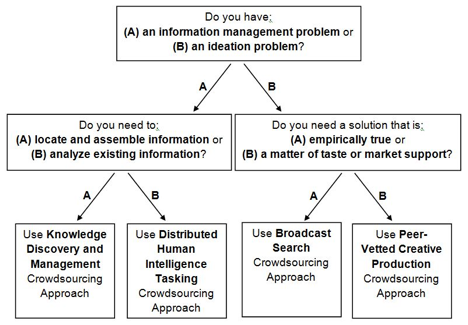

Lauriault believes that Canada’s government is failing to meet the promise held out by new technology and open data. That’s because it’s falling way behind in actually engaging citizens in public policy debates even as it closes institutions such as Canada’s census, scientific organizations or civil society groups that produce this data. In essence, the government’s plan has gotten really good at creating more efficient e-government services but, for Lauriault, this is a very limited view of what open government and open data should be.

As an indication of this failure, Lauriault asks a simple question. Each year the Federation of Canadian Municipalities undertakes a quality of life indicator system that measures a number of factors including the environment, economy, sustainability, poverty and accessibility. Working with approximately 110 indicators and 200 variables, the organization surveys more than 40 different government organizations, including 24 cities across Canada.

“Can we go to that federal portal and could we construct that indicator system with the data in that portal? No. We’re still at the making cold calls, trying to find that public official who knows something about, you know, personal bankruptcies or whatever dataset that we’re looking at on the federal level—an expert at citizen immigration— and so on to collect those data, every year, to construct that indicator system.”

She points out that there are a number of civil society organizations which already do quite good work with data—often data they’ve had to collect and create an infrastructure for themselves. For example, the Canadian Council on Social Development’s Community Data Program has undertaken capacity building, held workshops, made community maps, created newsletters and worked with data all in collaboration with local groups like fire and police departments, anti-poverty organizations, school boards and ethnic groups.

“They’ve been doing that kind of data literacy piece on the front lines, but they’re not called open data. They’re just doing this for evidence-informed policy. So I think it’s not just the fault I think of the Treasury Board secretariat of Canada. I think that there is this kind of epistemic disconnect between, you know, civil society that works with data on an ongoing basis to inform policy and those who make apps.”

And it’s this dichotomy, Lauriault believes, that’s at the heart of why Canada’s Action Plan for Open Government 2.0 is failing to engage citizens and groups interested in policy.

“If the strategy is going to be innovation and economic return then we’re going to stay with app developers. That’s what’s going to stay as an open data planned strategy and outreach plan. If we think it’s about democratic deliberation and evidence-informed policy and real public engagement, then the strategy has to be different and how the open government plan and open data plan are evaluated also has to differ and change.”

[Geothink.ca theme music]

[Voice over: Geothoughts are brought to you by Geothink.ca and generous funding from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.]

###

If you have thoughts or questions about this podcast, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.