Dr. Harrison Smith recently completed his PhD at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Information under the supervision of David J. Phillips and co-supervised by Geothink co-applicant Dr. Leslie Shade (University of Toronto). In this article, he tells us how his research examined the impact of location data in marketing. Dr. Smith’s next endeavour is a post doctoral research position at Newcastle University’s Global Urban Research Unit in the UK under the direction of Roger Burrows and Steve Graham.

By Harrison Smith

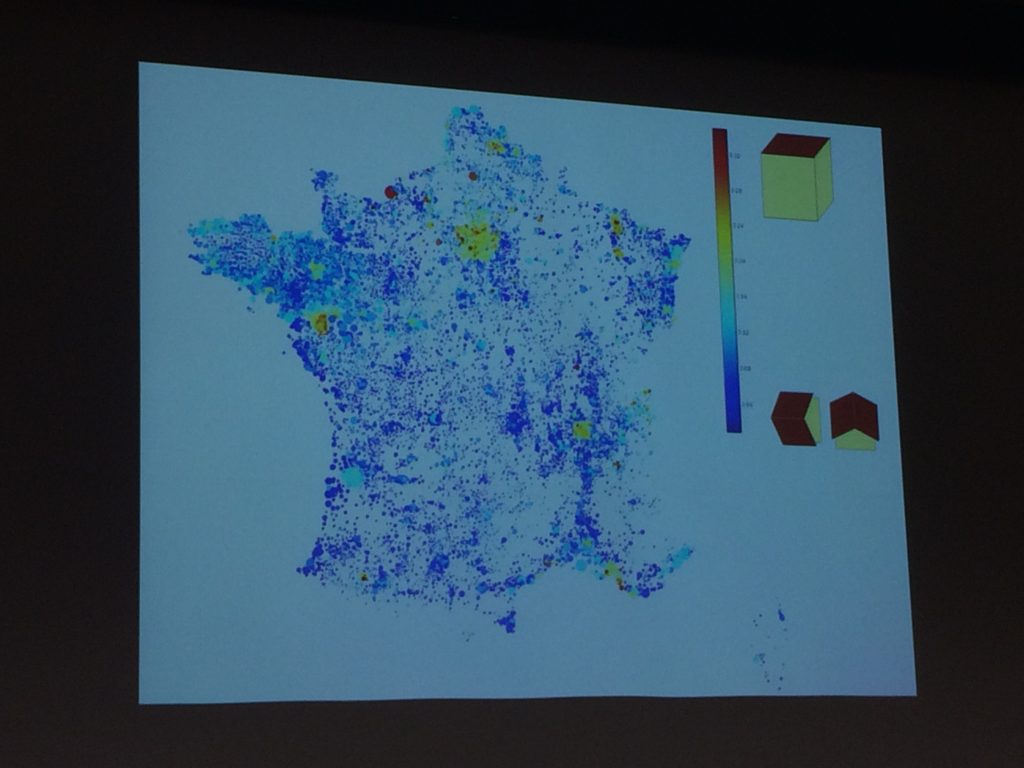

My dissertation, “The Mobile Distinction: Economies of Intimacy in the Field of Location Based Marketing”, examines the cultural and economic significance of location data in new kinds of marketing applications. When you survey existing research on location-based media, you tend to see a focus on user-centric studies that examines how these new interfaces can produce new kinds of intimacies and affective relationships between people and places. While certainly important, I argue there is a gap in our understanding of the political economy of locative media, and in turn the geo-spatial web, particularly with respect to how audiences are commodified and classified into specific segments through location data. I hypothesized that marketers are using location data to measure consumer lifestyles and tastes in ways that are similar to geodemographic classification. Traditionally, audiences are segmented by postal codes; in my dissertation, I sought to understand how location data can be used in a similar way to measure and classify lifestyles along particular hierarchies of cultural and economic worth. This allows us to theorize a broader political and cultural economy of the geo-spatial web, and questions certain dominant beliefs concerning the relationship between interactive cartography, big data, and power, particularly as urban environments are increasingly mediated by mobile for a variety of civic and commercial applications.

I focused specifically on the emergence of location based marketing using Pierre Bourdieu’s conceptual framework of habitus, capital, and field. I gathered my data through qualitative interviews with mobile and location-based marketers, participant observations of marketing conferences, as well as document analysis of mobile and location based marketing literature.

I asked two basic questions:

- What is the political economy of location data in mobile and location-based marketing?

- What are the underlying values, beliefs, philosophies of location data in the field of location based marketing?

These two questions are complimentary because the economic value of location data is contingent upon how marketers can successfully imbricate audiences into new fields of cultural production by appealing to specific logics of consumer lifestyles and practices through mobile media. Put differently, I discovered that the potential success of location based marketing depends on audience consent to participate and interact with marketers. This is important because it reveals a deeper level of understanding about geo-locative media and data that is structured by social, cultural, and economic relationships between consumers and institutional forces such as marketers.

I was particularly interested in understanding the specific values and philosophies that marketers are trying to enact in order to reveal how location data can inform geodemographic classifications using new kinds of metrics. I discovered that marketers employ numerous strategies for collecting location data from audiences that extend beyond GPS sensing. Sometimes, audiences may not even realize this is happening on an everyday basis because of the numerous methods it is possible to collect or infer location data from smartphones without our knowledge. For example, in some cases, location data is not actually collected by marketers themselves, but instead harvested from third party advertising exchanges during routine advertisement requests. When that happens, location data can be used to measure the efficacy of advertising. Third parties analyze the extent to which mobile advertising can drive audiences into particular stores, effectively offering a mobile measurement for audience conversion rates, namely by driving audiences into particular locations.

Furthermore, this can also be done through the passive collection of MAC (media access control) addresses, which are unique identifiers for hardware that are broadcast by smartphones on regular intervals. This is interesting because it represents a non-intrusive method for collecting location data. It is also worth considering how this kind of location data could also be used by non-commercial institutions, such as urban planners. In fact, there are many examples in which public spaces such as parks are now layered with sensors that collect location data from visitors, and can measure who they are, where they came from, and what other places they visited.

However, this is not an inevitable trend in the future of smart cities, as I argue that the capacity for collecting location data depends on the production of consent or the negotiation of resistance. A lot of work and investment must be done to convince large brands and individual stores of the value of targeting consumers in this way. The smartphone is a very personal, intimate device, and there may be resistance from consumers to letting marketers track them all the time, with ubiquitous access to their location history, or the ability to send targeted push notifications to mobile audiences in specific locations. This necessarily brings up important ethical questions around surveillance and privacy, as well as the kinds of lifestyles and consumer practices that are encouraged through mobile media. In my own interviews, many marketers side-stepped the issue of privacy by focusing instead on the inherent value exchange of data for various kinds of rewards or distinctions.

We will definitely see many different conversations emerge around how location data intersects with our values and attitudes towards surveillance in increasingly automated urban environments. In an interdisciplinary context such as Geothink, this will allow us to ask better questions concerning the value of location data, and be more critical on these issues.

I would like to thank my supervisory committee, which includes David Phillips, Leslie Shade, and Ronda McEwan. I also want to thank Geothink, particularly for the friendships I have developed on the team, and which has helped me appreciate the broader significance of my research.