Geothink students, staff and faculty at the 2017 Summer Institute at McGill University in Montreal, QC.

By Drew Bush

We’re very excited to present you with our 14th episode of Geothoughts. You can also subscribe to this Podcast by finding it on iTunes.

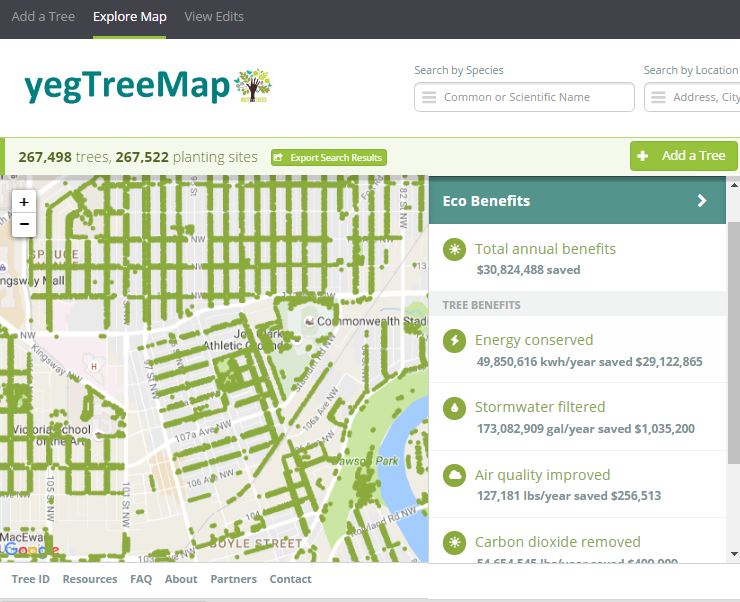

In this episode, we take a look back at Geothink’s 2017 Summer Institute at McGill University in Montreal, QC from May 25-27. The theme of this year’s Institute was “Smart City: Toward a Just City.” An interdisciplinary group of faculty and students tackled many of the policy, legal and ethical issues related to smart cities.

Each of the three days of the Summer Institute combined workshops, panel discussions and hands-on learning modules that culminated in a competition judged by Montreal city officials and tech entrepreneurs. The goal of the competition was for student groups to develop and assess the major principles guiding Montreal’s 2015-2017 Montréal Smart and Digital City Action Plan.

Thanks for tuning in. And we hope you subscribe with us at Geothoughts on iTunes. A transcript of this original audio podcast follows.

TRANSCRIPT OF AUDIO PODCAST

Welcome to Geothoughts. I’m Drew Bush.

[Geothink.ca theme music]

“Smart cities, what do we even need humans for anymore? As you can see from this morning’s panel, smart cities are more than urban engineering, they’re more than the sensors, they’re more than efficiency. Part of going beyond these things, part of creating empathy—my provocation at the beginning of the break—was…is to engage citizens. And how we actually do that, and how we actually do that in the context of a smart city will be discussed by Pamela Robinson and Rob Feick.”

That’s Geothink Head Renee Sieber, associate professor in McGill’s School of Environment and Department of Geography, addressing Geothink’s 2017 Summer Institute that just concluded this past May 2017. She was kicking off the afternoon presentations and work sessions on day one of Geothink’s annual Summer Institute this year held at McGill University in Montreal, QC from May 25-27. The theme: “Smart City: Toward a Just City.”

Each of the three days of the Summer Institute combined workshops, panel discussions and hands-on learning modules that culminated in a competition judged by Montreal city officials and tech entrepreneurs. The goal of the competition was for student groups to develop and assess the major principles guiding Montreal’s 2015-2017 Montréal Smart and Digital City Action Plan.

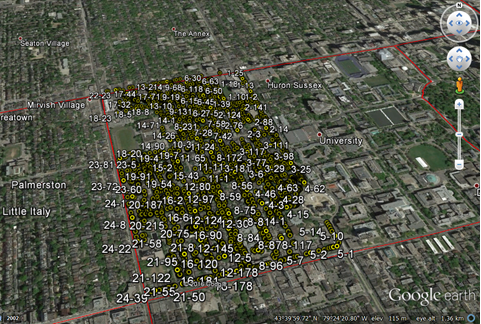

To start off the afternoon’s work, Rob Feick, an associate professor in Waterloo University’s School of Planning, discussed the idea of civic participation.

“All right, all right, so we’re going to take a few minutes and talk about this idea of civic engagement and how we might conceptualize that in the smart city context. How it might be different from how we think about engagement and civic participation in the pre smart city world. Ok. So. Interesting times: We have a lot of problems. That isn’t meant to get you depressed. I want you to be thinking of this as challenges. So there a lot of interesting, tough challenges that all of us need to apply ourselves to in some way or another.”

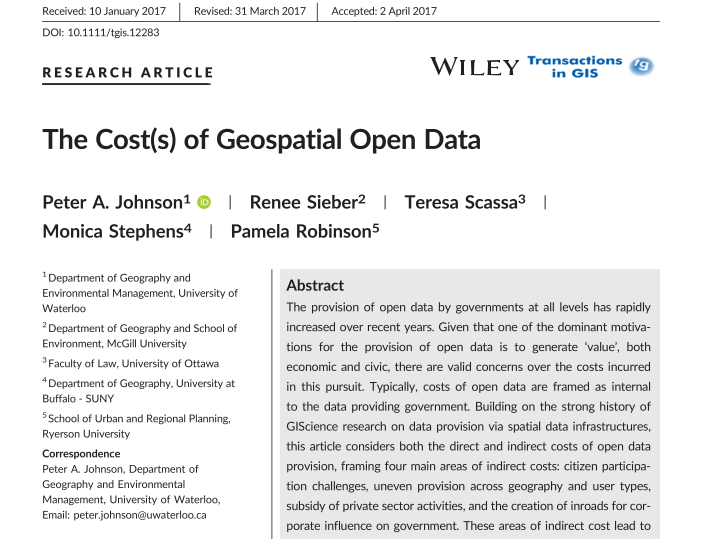

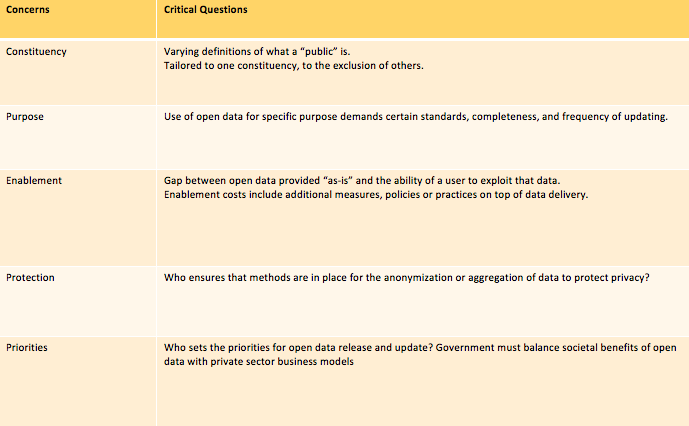

Pamela Robinson, associate professor in Ryerson University’s School of Urban and Regional Planning, added to this call for action by presenting the work of her graduate students who created an evaluative framework for smart cities as part of Geothink.

“Ok. So I’m asking everyone to dig into your blue bags and pull out the piece of paper that looks like this. And I’m going to transition from Rob’s talk about broad ways of thinking about civic engagement in the smart city to transitioning to a tool that was created by graduate students of mine as part of this project last fall as part of Geothink. And we wanted to share it for a couple of reasons. One, one of the challenges I think when you bring people together of different disciplinary backgrounds is that people have different ways of talking about the same kinds of issues.”

“And one of the things we hope that you’ll have kind of expanded capacity over the course of this two and a half days is you’re going to learn how to listen and talk to each other slightly differently. And one of the ways we want to accelerate that is by giving you something to think about. The other reason I want to bring it forward is I’m really proud of the work these students did. And I think it’s a good way of showing you as students inside this grant that your work can make a difference.”

This theme of empowering the next generation of academics and practitioners to build more just and sustainable smart cities of the future was woven throughout the three days of sessions. It grew more tangible later in the first day when students heard from Montreal City Council Chairman Harout Chitilian. In an interview after his talk, he expressed a need for people to hire who possess unique skillsets and competencies important to designing services for smart cities such as his.

“Process improvement is a very complex and difficult task. Like I said, technology is the easy part. And process improvement takes those skillsets that I mentioned [in my talk]. For example, you know, very talented project and program managers that can put in place transformational projects to rethink the services of the city of Montreal. You need to have also different competencies—not only technological. But, for example, legal backgrounds, regulatory backgrounds—to make sure that your future new and improved processes comply with the legislation and the and regulatory framework in which that you are operating in. So, biggest challenge, bar none for me, is to hire, to retain, and to train the best skilled workers. Because skillsets, competency is the main ingredient to achieving all these different exciting initiatives.”

In Montreal, plans include improving the cities smart offerings in a variety of areas that require trained workers.

“I think we need to make very strong progress in the transit domain, so have real-time data of all the transit assets of the city of Montreal. We need to also have real-time data, like I said, for beach goers. For using the different beaches now. The portals are setting up. There is one in Verdun. So environments—so water quality data, air quality data. So that is very very important going forward. And last but not least for me, we also need to have democracy related data that is available to our citizens. For example, how your elected official voted on a certain subject.”

Chitilian set the stage for the three-day Institute but its faculty and participants kept each talk and activity lively and engaging. Thanks to Geothink’s five-year length as a grant, many relationships have been shaped by years of collaboration between co-applicants, collaborators, partners and students. As a result, the Summer Institute can be a good time to reflect.

For one former Geothink graduate student who is now an assistant professor in the Department of Geography at University of Calgary, that means considering the progress Geothink has made educating her peers on topics such as smart cities, open data, crowdsourcing and volunteered geographic information. Those have been the topics of the four summer institutes hosted by the grant—each of which Victoria Fast has attended.

“Actually, interestingly, something we haven’t touched upon yet is the synergy between all of them. You know, Institute number one in Waterloo was volunteered geographic information (VGI) and crowdsourcing, the second one in Toronto was crowdsourcing, and this one is smart cities. And all of those concepts are just so fundamentally embedded in each other. And for—I think students who have been to all of them really get this diverse and rich perspective on Geothink from these kind of very relevant topical areas.”

[Geothink.ca theme music]

[Voice over: Geothoughts are brought to you by Geothink.ca and generous funding from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.]

###

If you have thoughts or questions about this podcast, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.