Rachel Bloom, Julia Conzon and Elizabeth Barber took questions from the audience on day three of the Geothink 2017 Summer Institute after talking about their career paths post Geothink.

By Drew Bush

Geothink Co-Applicant Stéphane Roche, associate professor in University Laval’s Department of Geomatics, chats with students during a coffee break on day three of Geothink’s 2017 Summer Institute.

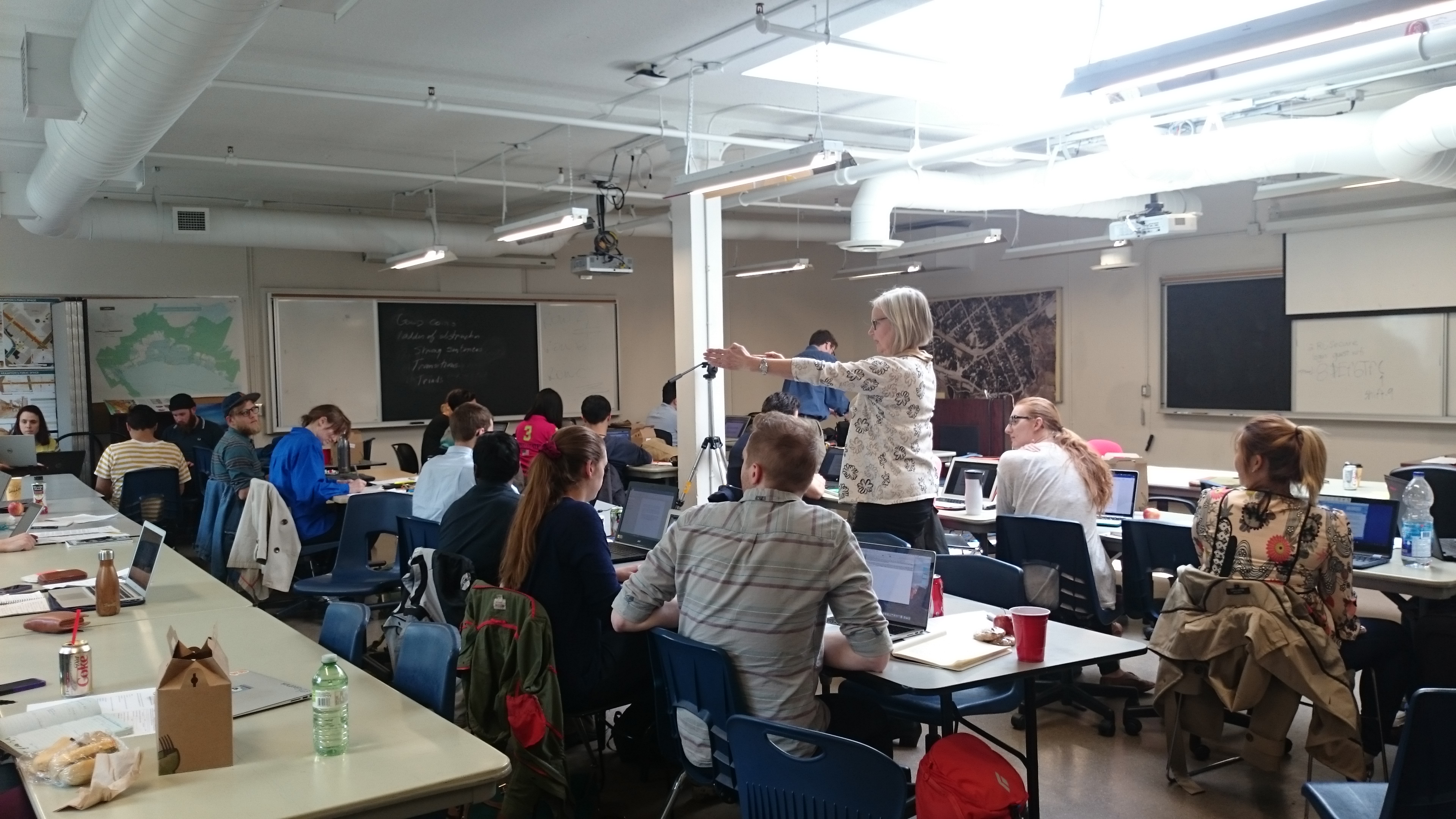

The third day of Geothink’s 2017 Summer Institute opened with Open North Executive Director Jean-Noé Landry discussing how Geothink’s collaborative approach begets research with practical applications for smart cities. A pair of Montreal entrepreneurs and a trio of former students elaborated on this perspective in their own subsequent presentations.

“We’re going to talk about enabling innovation,” Noe said to start the morning. “I’ve been following some of the conversations that you’ve been having with all these great folks that have come in over the course of the week…And today, you know, we’ve got an opportunity to look at a few people that have been able to do some great work.”

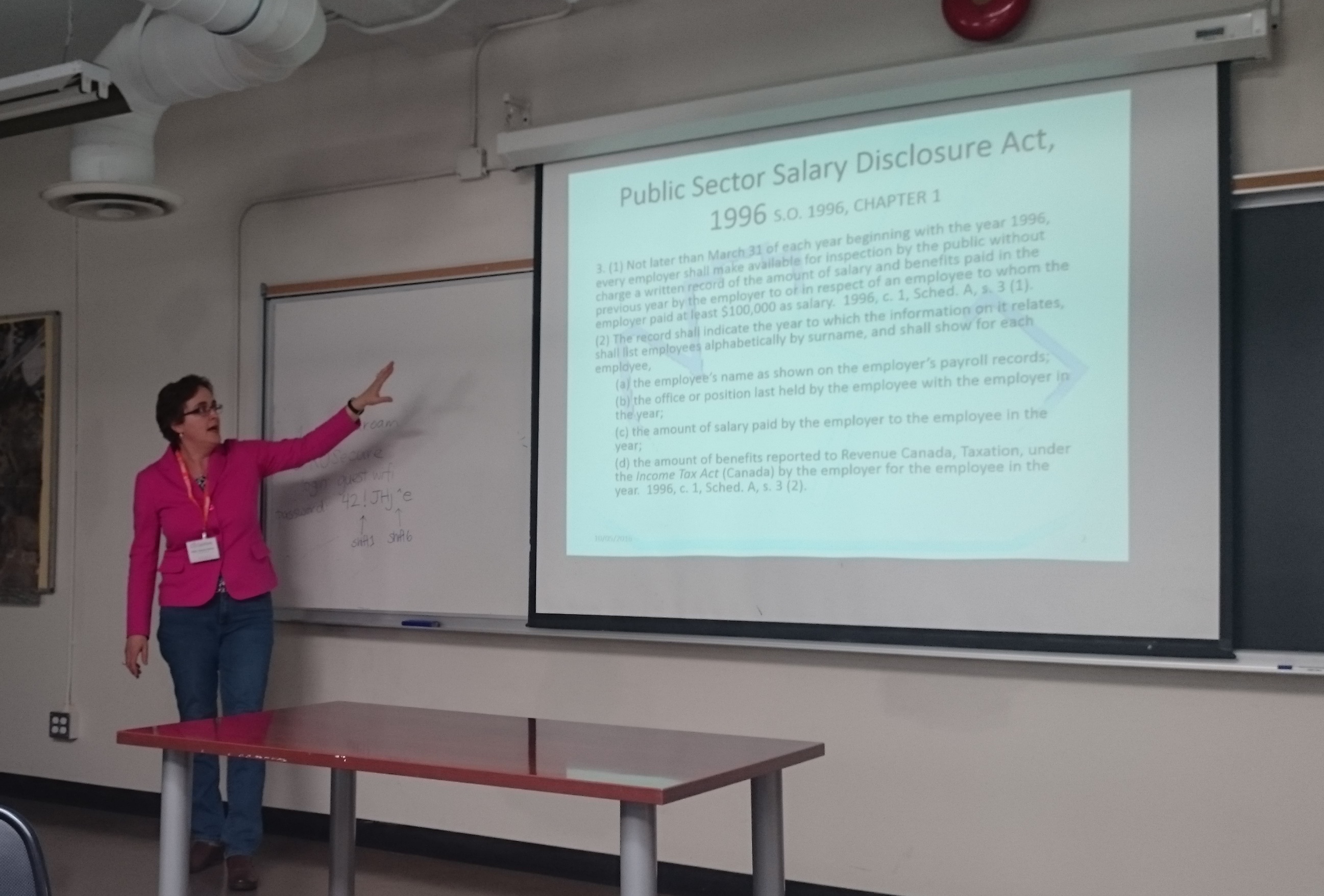

Two previous Geothink students followed with talks on their differing career trajectories after graduating from McGill University. Rachel Bloom is currently working as the project lead for Open North on Smart Open Cities; and Julia Conzon spoke of her work with open data at Statistics Canada. Elizabeth Barber, a master’s of public services student at University of Waterloo, talked about her summer work with the City of Montreal. They were preceded by Xavier Peich, a co-founder of SmartHalo, and Vincent-Charles Hodder, a co-founder of Local Logic.

The theme of this year’s Institute was “Smart City: Toward a Just City.” An interdisciplinary group of faculty and students tackled many of the policy, legal and ethical issues related to smart cities. Each of the three days of the Summer Institute combined workshops, panel discussions and hands-on learning modules that culminated in a competition judged by Montreal city officials and tech entrepreneurs. The goal of the competition was for student groups to develop and assess the major principles guiding Montreal’s 2015-2017 Montréal Smart and Digital City Action Plan.

The last day provided ample time for students to work within their groups to analyze Montreal’s strategic plan in accordance with a research question assigned by one of the Summer Institute’s faculty members. It also provided time for faculty members who once had been students themselves to reminisce.

“I love the summer institute,” said Victoria Fast, an assistant professor at University of Calgary’s Department of Geography. She herself has participated in the previous summer institutes in 2016 and 2017 and had just recently made the transition to faculty.

“Actually, interestingly, something we haven’t touched upon yet is the synergy between all of them. You know, Institute number one in Waterloo was volunteered geographic information (VGI) and crowdsourcing, the second one in Toronto was crowdsourcing, and this one is smart cities. And all of those concepts are just so fundamentally embedded in each other. And for—I think students who have been to all of them really get this diverse and rich perspective on Geothink from these kind of very relevant topical areas.”

“This one, in particular, I really like from the student perspective, the employment opportunities is really great to hear,” Fast added about the presentations on life after Geothink. “The idea of social entrepreneur, social innovation. I think students in a university really need some hope about jobs and job prospects.”

The Summer Institute faculty, city officials and tech entrepreneurs helped to judge the work of each student group at the end of the day. But the real value lay in the new ideas and understandings each student gained.

One group explored which city services should be prioritized for digitization first while another determined how to quantify what appropriate inclusion of citizens in smart cities of the future might look like. Others examined what open data should be released by cities, the advantages of public Wi-Fi, and how cities can foster collaboration between innovators.

“We tried to develop sites for innovation learning,” Seyed Hossein Chavoshi, a PhD student from Laval University, said. “So there are many things actually we want to take into account. For example, there are the functionality and the design of the place where we want people, for example, to test apps that are actually developed by the municipality. So to do that and to find these places there are many aspects. The functionality is one of them. Another is the ethic. But the functionality is a core one of them—when you want to invite citizens from different cultures, from different groups, from different ages you have to find a place that can at least accommodate all different ages.”

Chavoshi added that he found this year’s Summer Institute quite informative.

“I’m so technical from an engineering point of view,” Chavoshi said. “But here we were so diverse. So like people from law and from a social geography background and [subjects] that, actually, they aren’t often gathered all together. So before that I didn’t actually know that we had to take into account all these aspects. But when I was here and I just listened to the other peoples’ points-of-view, from their background, it helped with when I want to, for example, develop something that can be fascinating to the citizens in a smart city.”

Geothink students, staff and faculty at the 2017 Summer Institute at McGill University in Montreal, QC.

###

If you have thoughts or questions about the article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.