By Drew Bush

We’re very excited to present you with our ninth episode of Geothoughts. You can also subscribe to this Podcast by finding it on iTunes.

In this episode, we examine a Geothink project on open data that officially kicked off in February 2015 with a Geothink teleconference call. Project lead Rachel Bloom, an undergraduate student in the Geothink Rapid Response Think Tank at McGill University, began this research one year ago. She worked with Geothink Head Renee Sieber, associate professor in McGill University’s Department of Geography and School of Environment.

It recently culminated in a white paper written on two spread sheets (1) an examination of high-value open datasets Canadian cities use; And (2) an inventory of open data standards published by open data providers. Listen in as Bloom explains to partners who publish open data how to know what standards exist and who uses them for which datasets.

Thanks for tuning in. And we hope you subscribe with us at Geothoughts on iTunes. A transcript of this original audio podcast follows.

TRANSCRIPT OF AUDIO PODCAST

Welcome to Geothoughts. I’m Drew Bush.

[Geothink.ca theme music]

“This project is about investigating open data domain specific standards at the Canadian municipal level, which I guess is kind of a mouthful. But basically I’ve created two spreadsheets to figure out how Canadian municipalities are publishing their data and how the level of conformity is per the guidelines for open data standards.”

That’s Rachel Bloom, an undergraduate student in Geothink’s Rapid Response Think Tank at McGill University, talking about domain specific data from sectors like transportation and city budgets. She’s working with Geothink Head Renee Sieber, associate professor in McGill University’s Department of Geography and School of Environment.

“To begin this project I chose ten domains to focus on. These domains came from open knowledge foundation spreadsheets. They are considered high value, and I thought these were interesting. I thought they were important to public use. So I chose them as the basis to create these spreadsheets.”

In late February, Bloom conducted a teleconference for the project’s partners in several Canadian cities. In it, Bloom discusses the project, each spreadsheet, and answers questions from those on the call. She starts with the first spreadsheet.

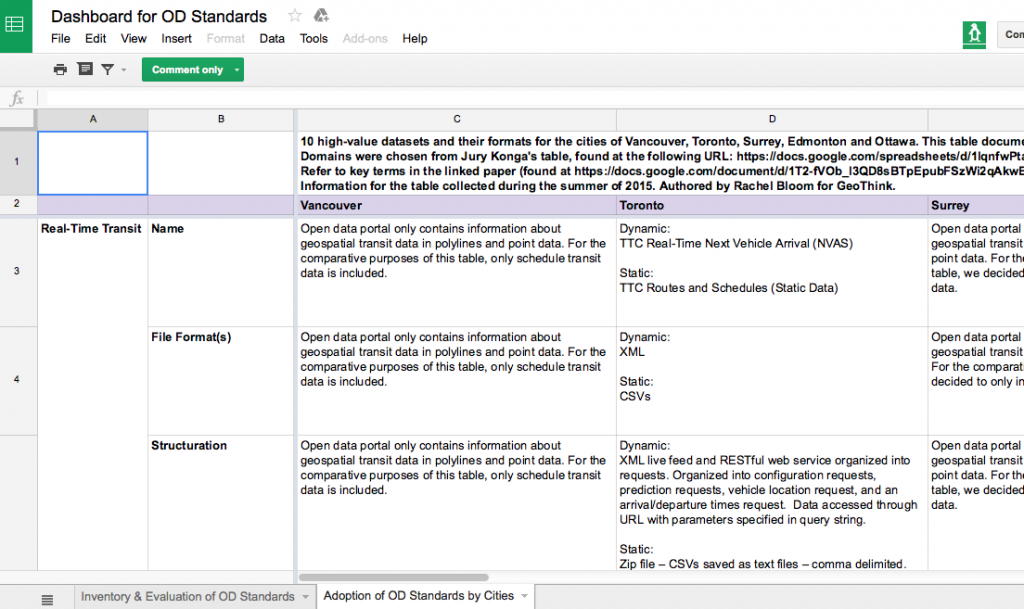

“It’s called ‘Adoption of Open Data Standards By Cities.’ So what we did for this is we have the 10 domains on the side on the y-axis, and then we have kind of nested between these certain metrics of how the municipality names the dataset, the file format, the structuration of the data, any metadata associated with the dataset or description of the data, and if theses data sets for each domain are already using specific data standards—open data standards. And these were taken from each municipality’s open data catalogues.”

“And it helped for eventually comparing whether the ways that data is being published is even kind of compatible with the semantic and schematic guidelines dictated by available open data standards.”

Participants then examined a specific example from the spreadsheet, building permits for the City of Toronto. The call then proceeded to the next spreadsheet developed.

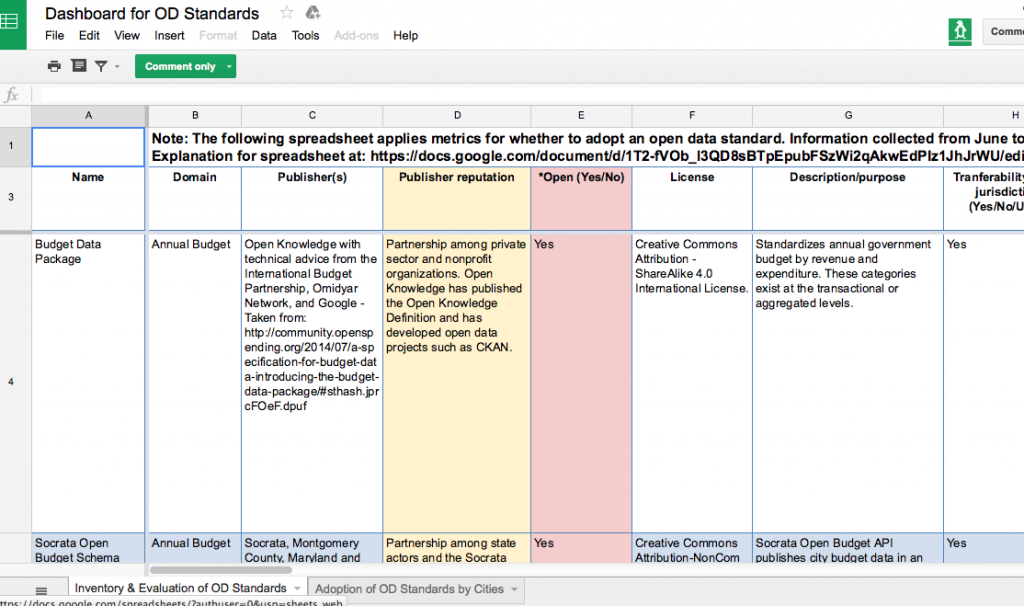

“It’s called ‘Inventory and Evaluation of Open Data Standards.’ Here we have on the y-axis these are individual open data standards that are kind of domain specific so they are pegged to certain domains and they cover the ten domains used for the other table. Though there is two extra domains…the metrics you find kind of on the top, are an innovation on my part. They were chosen by me based on the demand of data publishers and consumers I found in my research which came from all different types of mediums.

“I’ve even read e-mail correspondences of people talking about what they want when they are structuring their datasets. They also come from reinforcing that these standards are open. So what does it mean to be open? They have to be open, they have to be consensus driven, they have to have to multi-stakeholder participation so theirs metrics have to account for that.”

Bloom again takes participants through a specific example, this time a budget data package, going through all the metrics to give participants a sense of the quality of standard in terms of making data interoperable. When she finishes, Linda Low, Open data lead for the City of Vancouver, interrupts her to ask:

“Rachel can you talk a little about the criteria for whether or not it’s open or not again, it’s whether multi-stakeholders contribute to it, and there was something else too, right, that you said?

“So when we talk about multi-stakeholders we’re talking about people who contribute that are from different facets of society. So the private sector, the public sector, civil societies, and also the obvious which is that open implies that there should be no royalties or fees associated with using the standard. It should be repurposable, they should be able to extend it how they wish, it should have a license that is open so that there is legal ramification for using the standard as you please. You’re right it’s not explicitly mentioned which of these kind of contribute to defining openness but all of these are good fundamental metrics for an open standard I would think.”

The teleconference proceeds as Bloom and the call’s participants discuss the spreadsheets and white paper, stopping to elaborate on specific examples or details in more depth. Toward the end of the 40-minute call, Bloom shares the vision and goals for this project.

“There’s metrics that can help publishers, but there’s also metrics that can help consumers who would want to voice how they want to structure the data which is really part of the open process. So I think it can be used as multiple, for multiple purposes, really so it’s flexible in that way. So I’m not sure if there’s a very specific way of using it cause it really depends on the goals of the person using the resource.”

She’s followed-up by Sieber who firsts asks a question and then provides insight into how the project’s goals were determined.

“A standard is likely to be viewed much differently if you want to do something for internal government use like business intelligence as oppose to external use. And depending upon the audience, if you’re doing something for realtors it might be viewed quite differently than if you’re trying to do it for, I don’t know, low information voters.”

At the conclusion, Low offers the municipal publishers perspective on how constantly updated and revised standards make it hard to know which one a municipality should adopt in differing domains such as city budgets, crime statistics, or waste removal services.

“When do we say this is justifiable for us without doing a whole bunch of research and wasting the effort afterward. That was the thing I always keep struggling about.”

Bloom doesn’t hesitate with an answer.

“There are so many options too and ways of approaching it. I mean, I don’t know–it’s really about the interests of the person who is publishing the data and the goals. I think at the end of the day, it’s going to, different governments are going to have reconcile what their goals are and how they want to go about it. Which is the hardest part.”

This project is ongoing and next steps will continue to look at the landscape of open data standards in Canada.

[Voice over: Geothoughts are brought to you by Geothink.ca and generous funding from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.]

###

If you have thoughts or questions about this podcast, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.