Citizen scientists help researchers transcribe historical climate records and photograph natural phenomena.

By Naomi Bloch

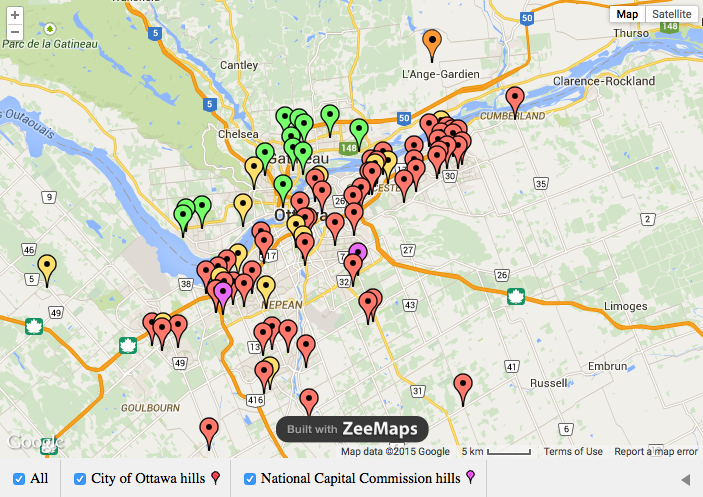

The concept of the science hobbyist — the backyard astronomer staring up at the sky or the amateur ornithologist taking part in the annual Christmas bird count — is hardly a new one. What is notable today, however, is the scale and scope of new collaborations between research institutions and volunteer citizen scientists. These kinds of citizen science partnerships have inspired a new study by Geothink co-applicant Teresa Scassa and doctoral candidate Haewon Chung, called “Managing Intellectual Property Rights in Citizen Science: A Guide for Researchers and Citizen Scientists.”

Chung, now a Geothink Ph.D. student researcher at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law, is interested in intellectual property (IP) law with a particular focus on digital ethics. Scassa is a Canada Research Chair in Information Law at the University of Ottawa. The two researchers will participate in a panel discussion and launch of their new work at the Wilson Center Commons Lab, in Washington, D.C., on December 10.

“Part of the point of the guide is to encourage people to take a proactive approach and think about what they want to get out of the citizen science project, and what they need to get out of the citizen science project,” Scassa said. “For example, if you need to publish your research results, or if you need to keep your data confidential because you’ve got private sector funding that requires that, how do you structure the IP side of things so that you can do that?”

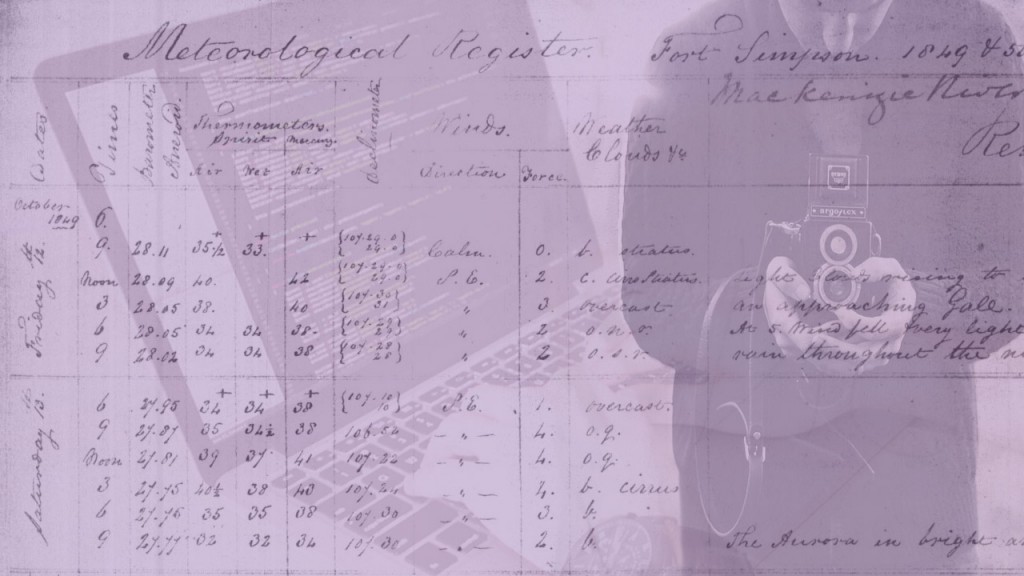

Citizen science, broadly construed, involves the participation of non-professional scientists in scientific data gathering and the production of new scientific knowledge. In the realm of Geothink, this generally takes place in the context of volunteered geographic information (VGI) and contributions to geographic knowledge. Some projects may involve volunteers helping with laborious tasks such as transcribing historical climate data. In other cases, participants may be sharing geocoded photos or video footage, recording audio, or producing text narratives. In countries like the U.S. and Canada, such original, creative efforts are inherently protected by copyright law — something participants themselves may not even realize.

Do you copy?

The 80-page report is divided into three parts, beginning with a concise review of relevant areas of intellectual property law including copyright, patent, trademark and trade secret law, as well as specific considerations involved in the protection of traditional knowledge. Though copyright law differs around the world, essentially copyright grants certain exclusive rights to the authors of creative works. These rights usually include the right to control how work is distributed, reproduced, and re-used. “It’s also significant because it arises inadvertently,” said Scassa.

Unlike other types of intellectual property such as patents, in many countries the creator is automatically granted copyright protections without taking any specific legal actions. “There are going to be copyright issues with respect to any website that’s created, and with respect to many different types of contributions that users might make, whether they’re text-based or photographs or video clips or whatever they might be,” Scassa said. “There are copyright issues with respect to compilations of data. And then, of course, those copyright issues are relevant if, for example, the researcher decides to publish in a closed access journal and the participants want access to those research results, and all these sorts of things.”

When institutional researchers initiate citizen science projects, there are commonly expectations regarding eventual publication of findings, data sharing, posting information online, as well as educational and civic aims. “Depending on the nature of the project, the users may expect to have total access to the research results — to any publications, but maybe also to all of the data that’s been gathered,” said Scassa. “So we encourage the researchers who are creating citizen science research projects to think about what the user community may be expecting from them in terms of the project design.”

Ethics and law in the balance

In the second section of the study, the authors explore some of the ethical issues that arise in light of IP law. This includes everything from appropriate attribution to uses of participants’ contributions as well as research output. “If you’re going to be collecting stories or traditional knowledge from a community, for example, then that’s going to result in some intellectual property,” Scassa said. “And the ethical requirements may be different from the bare legal requirements. Part of it is being aware of what the legal defaults are and how those might need to be altered in the context of the relationship that you have with your participants.”

Scassa notes that researchers’ relationship with citizen scientists is generally one among many. “Researchers at universities have a complex web of relationships,” Scassa said. “Their universities have IP policies; those IP policies might provide that all IP stemming from this research may belong to the university and not the researcher, so they may not be able to promise certain things in their projects. Their funders may have expectations, and their publishers may have expectations. They may also have expectations in terms of the ability, perhaps, at some point in the future to patent some of their research. So they have this complex web of relationships and their relationship with citizen scientists is one of those relationships. We encourage them to think about this web of relationships and these expectations and try and design accordingly.”

To help with this process, the third section of the study guides readers through the various types of licensing options that can be applied. The authors provide diverse examples from real-world citizen science projects both local and global, and a toolset to help project designers as well as participants understand their options. “We don’t want to create barriers,” Scassa said. “It’s a really complex area. We’re trying to make it as accessible and as useful as possible, just to try to get people thinking about these ideas.”

The Wilson Center panel discussion, “Legal Issues and Intellectual Property Rights in Citizen Science,” takes place at the Wilson Center Commons Lab, Washington, D.C., Wednesday, Dec. 10, 11am –12:30pm ET. There will be a live webcast of the event.Interested in learning more about intellectual property law and citizen science? Reach out to Teresa Scassa on Twitter: @TeresaScassa.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Naomi Bloch, Geothink’s digital journalist, at naomi.bloch2@gmail.com.