This is a guest post from Geothink Post Doctoral researcher James Steenberg, Ryerson University School of Urban and Regional Planning, working with Dr. Pamela Robinson.

By James Steenberg, PhD

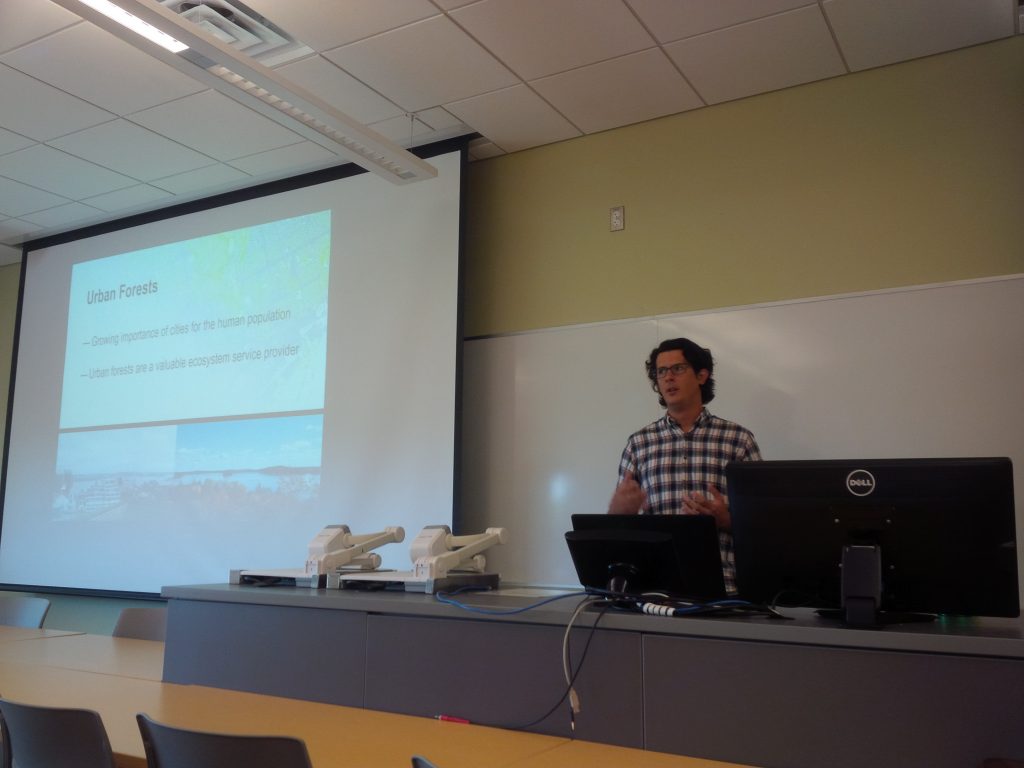

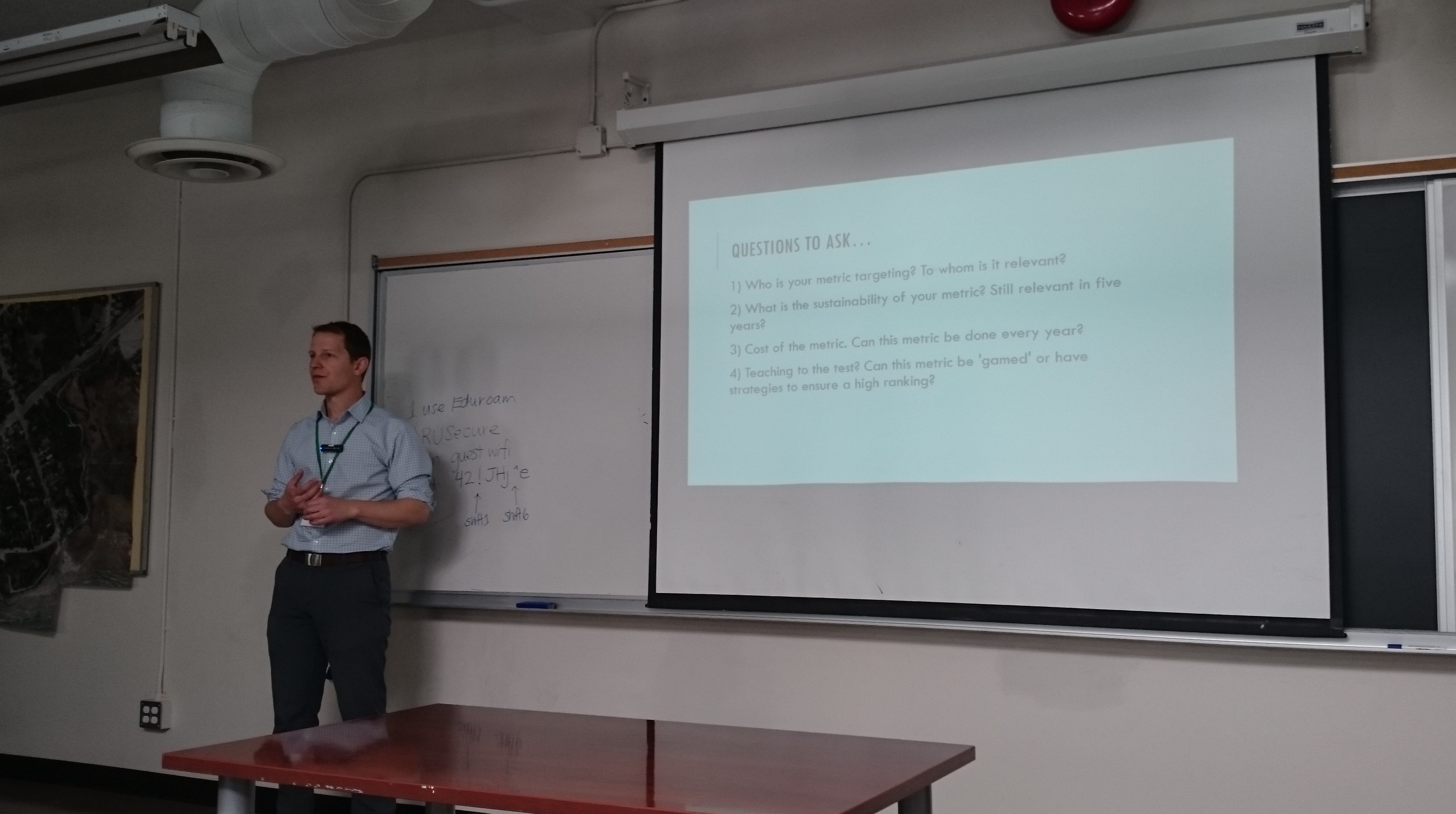

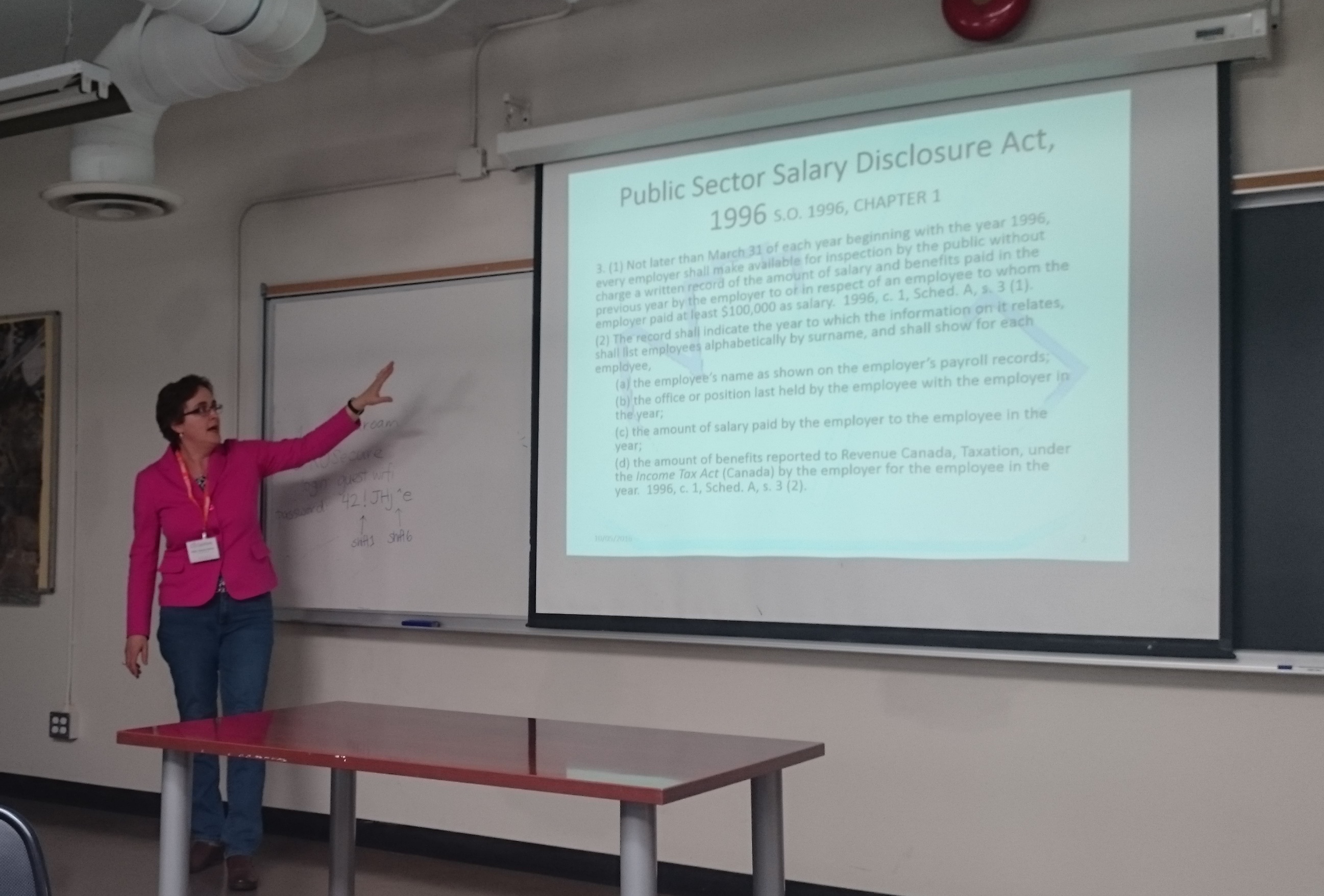

I recently had the opportunity to go on a Geothink summer exchange at the University of Waterloo hosted by Dr. Peter Johnson, a Geothink co-applicant and Assistant Professor at Waterloo’s Department of Geography and Environmental Management. The main goal of the exchange was to learn about open data and open government from Dr. Johnson with the ultimate goal of writing a collaborative paper on the potential role of open data in municipal urban forestry.

I wrote about my experiences during the exchange in a previous post, and subsequently left Waterloo with an open question on open data – can the open data/open government movement also be embraced in urban forestry? I would like to justify this question with two contrasting tales of cities.

Toronto

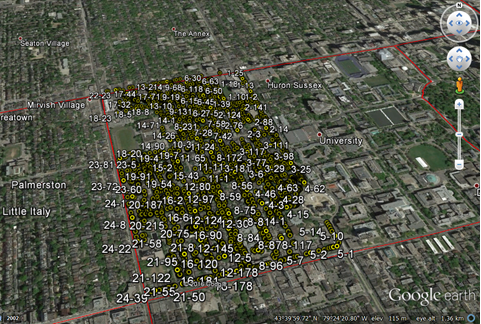

The first tale is about Toronto, more specifically about a neighbourhood in Toronto called Harbord Village where I conducted some of my PhD field research. The neighbourhood and its residents association are quite active in the stewardship of their urban forest. They even undertook a citizen science initiative to inventory and assess all 4,000 of their trees. I re-measured some of their tree inventory in 2014 with the purpose of identifying social and ecological drivers of urban forest vulnerability (e.g., tree mortality). Soon after, my current Geothink supervisor Dr. Pamela Robinson and I began to speculate that a key agent of change was housing renovation. Where we noted incidences of tree mortality, there were often shiny new home additions or driveways where once a tree stood. Fortunately, the City of Toronto’s open data portal includes building permit data and we were able to test this theory. We did indeed find that building permits (i.e., housing renovation) significantly predicted higher rates of tree mortality.

Municipal urban forestry departments are responsible for planting, maintaining, and removing trees on public land, as well as protecting and sustaining the urban forest resource on public and private land through various policies and regulations. However, it’s important to note that urban forestry is plagued by management challenges due to the limited space and harsh growing conditions of cities. Simply put, trees frequently die when they’re not supposed to – often for unknown reasons – and practitioners are continuously seeking out ways to reduce unnecessary tree mortality. Our findings suggest that urban foresters aren’t talking to urban planners when they should be, or vice versa. Urban planners collect data describing where building renovation occurs. Urban foresters collect data describing where city trees are dying and being removed. Blending these datasets has revealed that better coordination and horizontal data sharing across branches of government might help keep public trees alive. More broadly, these findings indicate an inefficiency in municipal service provision – the provision of the beneficial ecosystem services that public trees provide to city residents. What other urban forest inefficiencies might open data reveal?

Edmonton

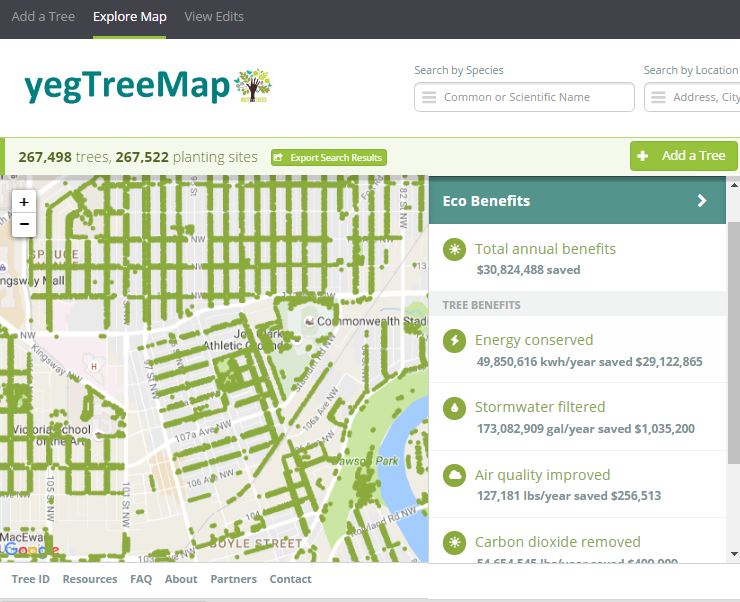

The second tale is about Edmonton and paints a different picture. I stumbled across one of Edmonton’s approaches to urban forestry during my summer exchange while learning about the various open data programs across Canada. Their urban forestry branch has used Open Tree Map – a web-based application for participatory tree mapping – in their yegTreeMap project so that “individuals, community groups, and government can collaboratively create an accurate and informative inventory of the trees in their communities”. In short, citizens in Edmonton that feel the urge to participate in municipal urban forestry can do so by downloading tree inventory data, using the data to their heart’s content (e.g., community-based stewardship programs), and entering new data into the City’s database.

This approach to what I’ve started calling ‘open urban forestry’ could conceivably improve citizen engagement with municipal government and its urban forestry programs. Much of the urban forest resource is situated on private residential property that the city doesn’t have direct access to, so citizen engagement in stewardship activities is a key piece of the puzzle. Moreover, urban tree inventories are notoriously fickle when it comes to data, being both expensive to generate and quick to become out-of-date and obsolete. Crowdsourcing a city’s tree inventory could conceivably provide better data to support decision-making in urban forestry, such as where to plant trees, what species to plant, and where trees are in decline or hazardous.

I have been very fortunate to be able to incubate these ideas with guidance from Dr. Robinson and her knowledge of urban planning and citizen engagement. Moreover, it was because of my Geothink summer exchange with Dr. Johnson at the University of Waterloo and his knowledge of open data and open government that I arrived at my current line of thinking on the benefits of open data and crowdsourcing for urban forestry. My next steps forward will be to think critically about these ideas as well. What are the environmental justice implications around who gets to participate in open urban forestry? Crowdsourcing tree inventories through open data programs may provide better data, but do they simultaneously justify the under-funding of municipal urban forestry programs? I’m excited to develop these collaborative ideas over the coming weeks and to hopefully answer my open question on open data.

My sincere thanks to Geothink for giving me the opportunity to go on a summer exchange at the University of Waterloo. Thank you Dr. Peter Johnson for hosting me at the Department of Geography and Environmental Management and for introducing me to your students and colleagues.

To the Geothink community members: please don’t hesitate to contact me if you have further questions or if you are considering going on a summer exchange yourself.

James Steenberg is a postdoctoral researcher under the supervision of Dr. Pamela Robinson at Ryerson University’s School of Urban and Regional Planning. His research focuses on the ecology and management of the urban forest. James can be reached by email – james.steenberg@ryerson.ca – and on Twitter – @JamesSteenberg