By Tenille Brown, PhD student in the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa

Recently, on March 3rd as part of the continuing Geothink Project, I hosted a Twitter chat about tort liability with Mapping Mashups. This online forum was joined by Geothink partners and friends and the primary topic discussed was the role of tort law and how and where it fits in the context of the Geoweb, liability and moral responsibility. One active participant of this Twitter discussion was British academic Muki Haklay, a collaborator on the Geothink project more broadly, and Haklay later wrote up some highlights from this discussion, available here. I have been considering the role of tort liability in multiple contexts for some time now, both prior to the online discussion and subsequent to it. I have not been thinking of this idea so much in a typical “finding a problem” lawyerly way, but more in a “trying to understand the allocation of responsibility” kind of way. From the legal perspective, questions about how we should handle the mountains of data collected and produced by governments and citizens alike, jumps out at me. For these reasons I chose to place the focus of the Twitter chat on tort liability rather than the challenges of protecting the privacy of personal information, or copyright issues in geospatial information, which have been discussed elsewhere.

With the increase in platforms and data sources (both government and volunteered) on the geoweb, there is also an increase in opportunities for legal liability to attach to this information. With Canadian cities releasing data sets of all types of information, from proposed roadways to beach water sampling data, the liability question is not hypothetical, but of increasing importance. Of course, cities are carrying out their due-diligence by ensuring personal information does not get released, following the principles of the open government license. But still, some questions remain to be answered such as, what legal tools are in place to deal with third parties who take government information and use that information in a way that causes harm?

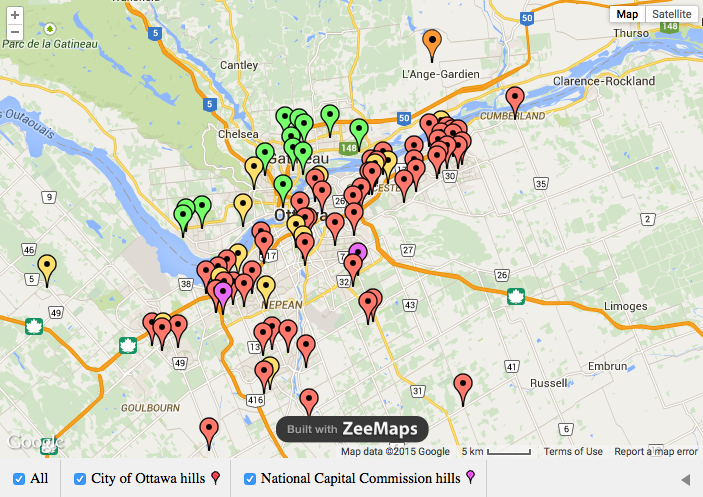

One example that immediately comes to mind is the use of open data to create apps for the reporting of pot-holes through cities 311 app, as happens in Toronto. A more apt example for Ottawa is the recently released information about hills open to tobogganing throughout the city, which was collated in a map here. Does liability attach to this information? If so, would information which highlights any hazards on the hill amount to a defence in a negligence action? How would we assign liability if citizenship were to take government data and create an open data app which contains outdated data?

In his write-up about the chat, I think Muki Haklay framed this problem correctly as an ethics problem. Haklay writes, “Somehow, the growth of the geoweb took us backward. The degree to which awareness of ethics is internalised within a discourse of ‘move fast and break things‘, software / hardware development culture of perpetual beta, lack of duty of care, and a search for fast ‘exit’ (and therefore IBG-YBG) make me wonder about which mechanisms we need to put in place to ensure the reintroduction of strong ethical notions into the geoweb. As some of the responses to my question demonstrate, people will accept the changes in societal behaviour and view them as normal…” In fact, tort liability principles recognize that if a wrong has been committed (sometimes even without intent), then the person who committed the harm might be required to compensate the individual. The very basis of tort law is that we ought to provide remedies for those wronged. Based on this aim, the courts don’t always uphold contracts of adhesion (which seek to limit liability).

The principles of tort liability understood as a matter of ethics and responsibility, provides opportunities for the prevention of harm and the accountability of government. This has long been recognized in the New York context, where the law stipulates that should a person trip on the sidewalk (or pothole), the city is only liable if it has been reported. To ensure reporting, every year the Big Apple Pothole and Sidewalk Corporationmaps out the cracks, holes and potholes throughout the city (and here). For its part, Toronto reports it has filled in almost 50,000 potholes in 2015 to date and over the past years there has been a 40% increase in drivers receiving compensation from pot-hole induced damage to cars. (The same report does not detail the number of complaints that have been made by the 311 reporting service).

TO Transportation has repaired approx 49,690 potholes to date this year. 1,438 potholes filled on Mar 13. #to_phcount

— TO Winter Operations (@TO_WinterOps) March 16, 2015

The twitter conversation demonstrates that legal analysis questions, such as who has standing to bring a legal claim, who bears legal responsibility for information, and which courts have jurisdiction, are only the beginning of tort legal questions. A second analysis begs that we understand data in a larger framework which takes into account duties and responsibilities. Focusing on the prevention of harm, we could argue, that there should be a larger set of core activities or areas for which liability cannot be contracted out. These core areas presumably would pertain to the health, safety and well-being of citizenship, particularly that they be tailored to protect the interests of those who cannot be expected to know the details of tortious liability, nor necessarily how to navigate geoweb activities.

Tenille Brown is a PhD student in the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa and a Geothink student member. Her research is in the areas of legal geography, including property, spatial and citizen engagement, in the Ottawa context.

She can be reached on twitter, @TenilleEBrown and via email, Tenille.Brown@uottawa.ca.