The bilingual federal Open Government portal

By Naomi Bloch

Teresa Scassa is a Geothink co-applicant researcher and Canada Research Chair in Information Law at the University of Ottawa. In a recently published paper, Scassa and co-author Niki Singh consider some of the challenges that arise for open data initiatives operating in multilingual regions. The authors use Canada’s federal open data initiative as a case study to examine how a government body in an officially bilingual jurisdiction negotiates its language obligations in the execution of its open data plan.

The article points out two areas for potential concern. First, private sector uses of government data could result in the unofficial outsourcing of services that otherwise would be the responsibility of government agencies, “thus directly or indirectly avoiding obligations to provide these services in both official languages.” Second, the authors suggest that the push to rapidly embrace an open data ethos may result in Canada’s minority language communities being left out of open data development and use opportunities.

According to Statistics Canada’s 2011 figures, approximately 7.3 million people — or 22 percent of the population — reported French as their primary language in Canada. This includes over a million residents outside of Quebec, primarily in Ontario and New Brunswick. Canada’s federal agencies are required to serve the public in both English and French. This obligation is formalized within Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as well as the Official Languages Act. Government departments are provided with precise guidelines and frameworks to ensure that they comply with these regulatory requirements in all of their public dealings and communications.

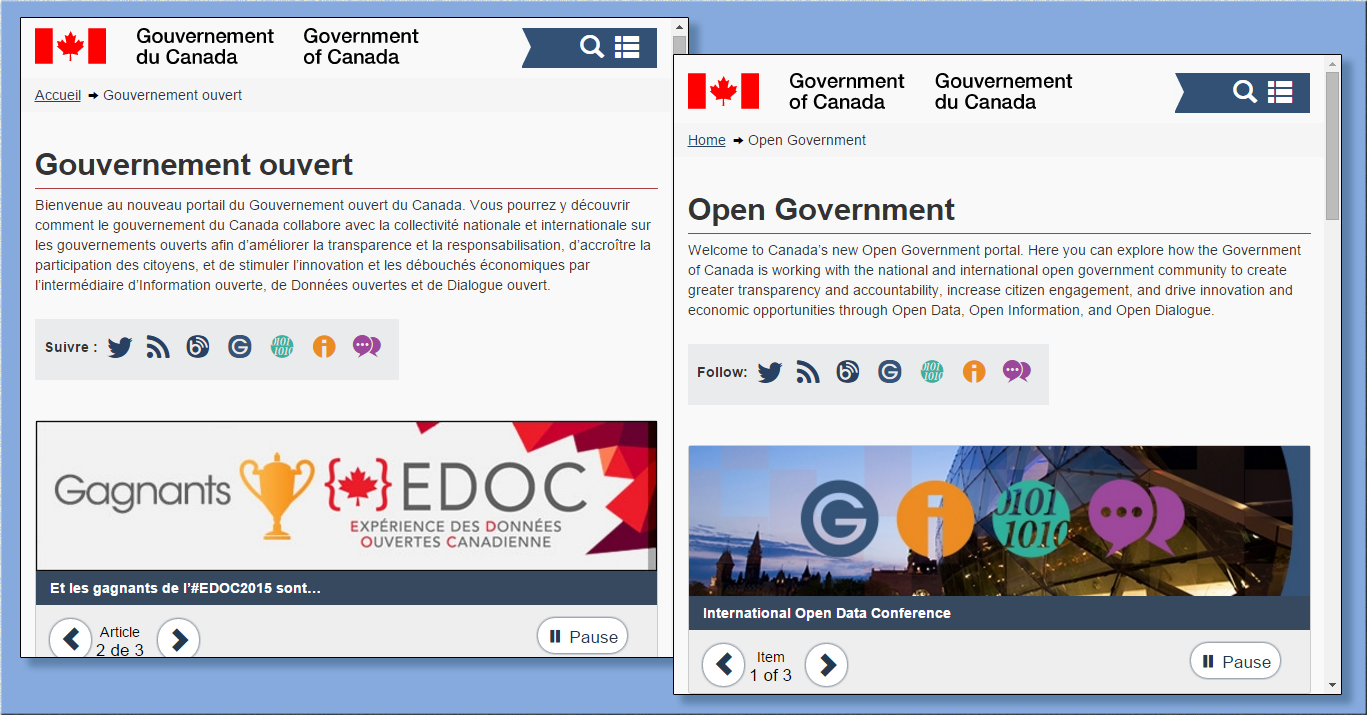

Scassa and Singh reviewed the various components of the federal open data initiative since the launch of the program to determine how well it is observing bilingual requirements. The authors note that while the open data infrastructure as a whole largely adheres to bilingual standards, one departure is the initiative’s Application Programming Interface (API). An API provides a set of protocols and tools for software developers. In this case, the API supports automated calls for open data housed in government databases. According to the authors, “As this open source software is not developed by the federal government, no bilingualism requirements apply to it.” While professional developers may be accustomed to English software environments even if they are francophones, the authors point out that this factor presents an additional barrier for French-language communities who might wish to use open data as a civic tool.

In their analysis of the data portal’s “apps gallery,” Scassa and Singh observed that the majority of apps or data tools posted thus far are provided by government agencies themselves. These offerings are largely bilingual. However, at the time of the authors’ review, only four of the citizen-contributed apps supported French. In general, public contributions to the federal apps gallery are minimal compared to government-produced tools.

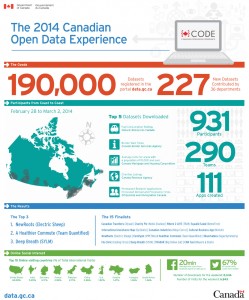

As part of their analysis, the authors also looked at the two Canadian Open Data Experience (CODE) hackathon events sponsored by the government in order to promote civic engagement with open data. Communications leading up to the events were provided in English and French. Government documentation also indicated strong participation from Quebec coders at the CODE hackathons, though native language of the coders is not indicated. Interestingly, the authors note, “In spite of the bilingual dimensions of CODE it has produced apps that are for the most part, English only.”

The 2015 event, which was sponsored by government but organized by a private company, had a bilingual website and application process. However, Scassa and Singh found that social media communications surrounding the event itself were primarily in English, including government tweets from the Treasury Board Secretariat. Given this, the authors question whether sufficient effort was made to attract French-Canadian minorities outside of Quebec, and if specific efforts may be needed to gauge and support digital literacy in these minority communities.

While it is still early days for Canada’s open data initiative, this case study serves to highlight the challenges of supporting an open data platform that can meet both legal obligations and broader ethical objectives. The authors conclude that, “In a context where the government is expending resources to encourage the uptake and use of open data in these ways, the allocation of these resources should explicitly identify and address the needs of both official language communities in Canada.”

Abstract

The open data movement is gathering steam globally, and it has the potential to transform relationships between citizens, the private sector and government. To date, little or no attention has been given to the particular challenge of realizing the benefits of open data within an officially bi- or multi-lingual jurisdiction. Using the efforts and obligations of the Canadian federal government as a case study, the authors identify the challenges posed by developing and implementing an open data agenda within an officially bilingual state. Key concerns include (1) whether open data initiatives might be used as a means to outsource some information analysis and information services to an unregulated private sector, thus directly or indirectly avoiding obligations to provide these services in both official languages; and (2) whether the Canadian government’s embrace of the innovation agenda of open data leaves minority language communities underserved and under-included in the development and use of open data.

Reference: Scassa, T., & Singh, Niki. (2015). Open Data and Official Language Regimes: An Examination of the Canadian Experience. Journal of Democracy & Open Government, 7(1), 117–133.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Naomi Bloch, Geothink’s digital journalist, at naomi.bloch2@gmail.com.