Shelley Cook, a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of British Columbia (UBC)-Okanagan, will be the recipient of Geothink’s first Dr. Alexander Aylett Scholarship in Urban Sustainability and Innovation (La Bourse Dr. Alex Aylett en Durabilité Urbaine et Innovation).

By Sam Lumley

Shelley Cook, a University of British Columbia-Okanagan Ph.D. Candidate and the first Geothink Dr. Alexander Aylett scholarship recipient.

Shelley Cook, a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of British Columbia (UBC)-Okanagan, will be the recipient of Geothink’s first Dr. Alexander Aylett Scholarship in Urban Sustainability and Innovation (La Bourse Dr. Alex Aylett en Durabilité Urbaine et Innovation). Her project empowers homeless populations in the city of Kelowna by building new connections with homeless service providers such as community housing organizations.

“I think It’s hard for me to articulate how much it means to me,” Cook said of this honour. “I’m utterly blown away by the privilege.”

Cook’s research was recognized because it closely aligns with the late Dr. Aylett’s vision for urban sustainability. His legacy for creative and durable solutions to social justice issues in cities lives on in Cook’s work. Dr. Aylett passed away on July 23, 2016 from cancer leaving behind a rich legacy of research into how cities can provide solutions on topics such as climate change and social justice using digital technology and open data.

Geothink’s Dr. Alexander Aylett Scholarship in Urban Sustainability and Innovation was established in his memory, to provide vital support to graduate students sharing Aylett’s passion for, and commitment to, sustainable urban development.

“I think after spending my entire career working with extremely marginalized populations, I think it’s difficult work,” Cook said. “And it’s work that I’ve seen over the years—you know, people working with the most vulnerable in society—it’s work that’s often not acknowledged. So I think, for me, I’m utterly blown away by the privilege and the fact that it is for work that is helping people who are the most vulnerable in the community. And I just feel incredibly honored in that respect.”

The award recognizes exceptional research contributing to the field of urban sustainability, and represents one way in which Dr. Aylett’s work is continuing to generate innovative, far-reaching impacts.

“Alex was an exceptional person and his presence seems to continue to surround those who knew and loved him,” Richard Aylett, his father, said. “And so, it is important that an award in his name goes to a project of value.”

Alex’ family is equally honoured to award Cook’s research noting in a e-mail to Geothink that “her work on mapping resources for homelessness in British Columbia corresponds with volunteer work that Alex did for street youth in Vancouver and is thus very appropriate.”

Cook’s work addresses an important issue faced by many communities where homeless populations are not able to efficiently locate suitable temporary shelter. Housing seekers and service providers have often lacked access to centralised, searchable information on gender-specific services, housing location and capacity.

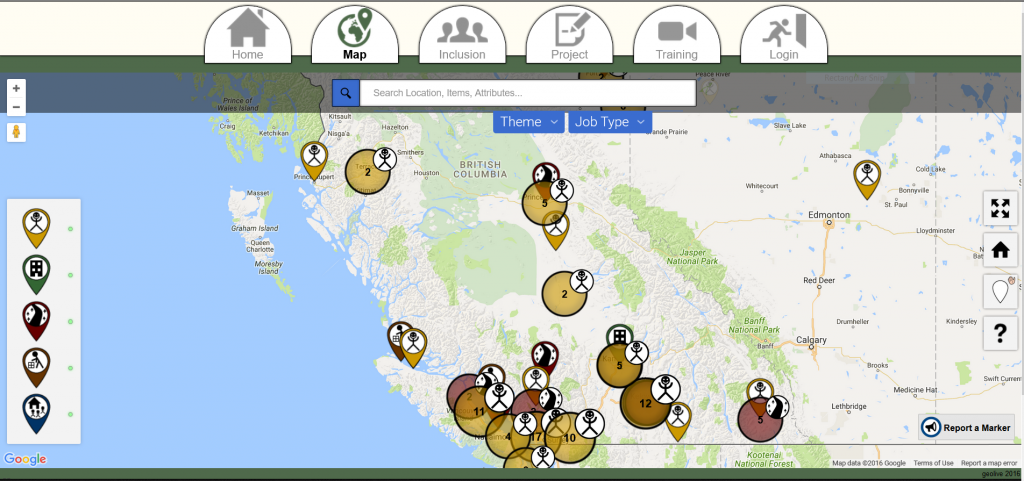

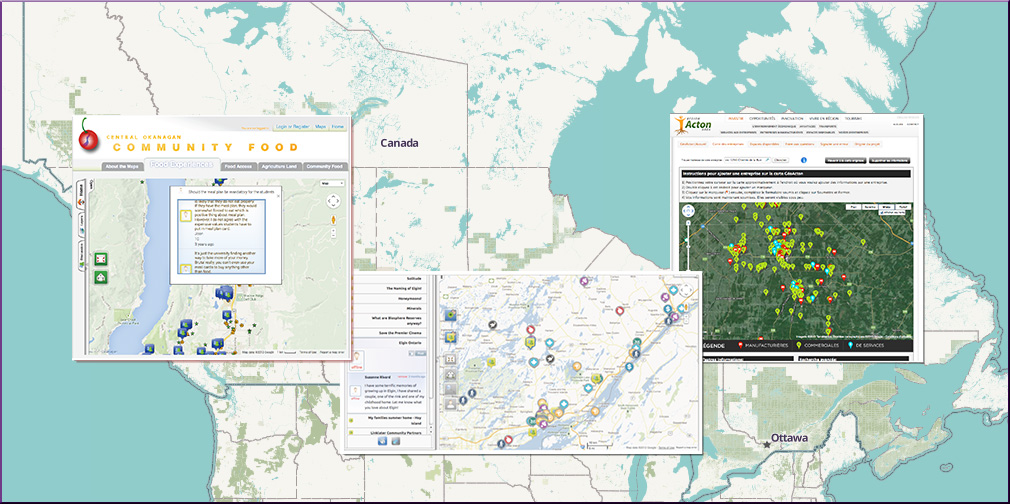

To confront this problem, Cook developed the i-Search Kelowna web map application (app). Supervised by Geothink Co-Applicant Jon Corbett, an associate professor in Community, Culture and Global Studies at UBC-Okanagan, Cook’s work is also supported by a team of researchers, funders and partners. Via the app, individuals seeking low-income rentals, emergency shelter and drop-in services are able to search for live, user-specific information about resource availability within the city of Kelowna.

Early feedback on the tool indicates that it is already providing users with a sense of ownership and advocacy over their own well-being and simplifying access to shelter information.

“It’s really about promoting empowerment, a greater sense of fairness and equity on the distribution of resources,” Cook said.

The project mirrors past volunteer work undertaken by Aylett that supported marginalised communities and contributed to his vision of cities as thriving, safe, and inspiring places for everyone to live. These are all values which Cook shares in her own work.

Cook emphasizes that partnerships formed between researchers, municipalities, businesses and community members are crucial to the development and durability of the project. By deeply routing themselves in the community, the researchers have made sure that their work has progressed to meet evolving needs and issues.

“I think again diverse groups with common interests can come together and create something that benefits the broader community,” Cook explains.

“Homelessness takes different forms over time, so we needed to make sure this tool was responsive and continuously informing strategies and approaches to the long-term issues,” she adds.

In this respect, the project has so far enjoyed a large amount of success. The City of Kelowna has embraced the platform to not only provide housing services but to inform its homelessness strategies and decision-making processes.

The generous support from the Dr. Alexander Aylett Scholarship in Urban Sustainability and Innovation is invaluable for ensuring continued commitment to the idea of cities as sustainable and equitable sites for innovation and development.

###

If you have thoughts or questions about the article, get in touch with Sam Lumley, Geothink’s newsletter editor, at sam.lumley@mail.mcgill.ca.