By Suthee Sangiambut

This article contains personal reflections from Geothink’s Newsletter Editor and Student Coordinator, Suthee Sangiambut.

This year’s Canada Open Data Summit and International Open Data Conference confirmed that open data and open government are quickly becoming mainstream topics for all sorts of disciplines and subject areas. I consider myself part of the open data community, due to my masters research on open data as well as my involvement in the Geothink grant.

I had heard of some of the people and institutions prior to the event and felt excited to have the chance to talk in person. My own interactions with representatives of government and non-profits had already indicated a lot of optimism and passion for open data and government. From this perspective, I got what I was expecting – plus an eagerness to tackle problems of implementation. My hopes of getting an update on the current status of open data in Canada were also met, especially with people from so many sectors and multiple levels of government.

The panels and workshops throughout the week were informative. In particular, I enjoyed Bianca Wylie’s great line that “open government is government,” as a way to set our expectations of how essential the idea of open data has become for many governments.

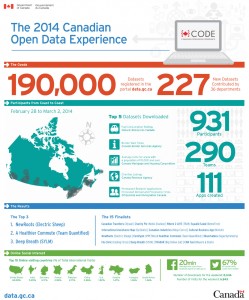

It was interesting to listen to speakers from Canada, USA, and beyond on different open data-related initiatives. The panels confirmed for me a couple of observations: those implementing open data and open government initiatives around the world are facing similar problems (such as resources, politics, organisational culture), engagement through one-off events (such as hackathons) is insufficient, and there is still work to be done to make studies and evaluations (especially in the non-profit sector) more rigorous.

I had assumed that there would be groups of attendees who would be sending different messages. However, after listening to talks on “Moving beyond the hackathon” at the Canada Open Data Summit, and various panels on “Open Cities” at the IODC, I found speakers at both making the same point—that citizen engagement with open data needs to go beyond one-off events such as hackathons, and that we need to address the issue of ‘capacity building’ or ‘data literacy’.

As an aside, this issue of ‘training in open data’ also surprised me as a conversation that was both too broad and too vague. And the idea of ‘open data skills’ should have been discussed in much more concrete terms, as attendees were not able to separate out what levels of programming or analytical skills were required. On the other hand, this level of vagueness was also quite appropriate, given the rate of change we experience in technology. In fact, attendees often spoke on similar subjects but used slightly different terminology.

I was also rather surprised to see representatives of organisations and governments implementing open data initiatives in developing countries. What was surprising for me was that, to some of them, open data was another tool to tackle corruption. The potential for open data initiatives in countries experiencing endemic corruption is quite different from countries with much lower levels of corruption. What attendees appeared to be assuming was that open data could be a catalyst for social change.

My main take-home points were on citizen engagement and the need for sustained engagement. Furthermore, the conversations on capacity building were very welcome, as they help to address the issue of keeping people actively engaged with open data in the long term. Increasing people’s programming and analytical skills could potentially increase their demand for data as they increase their capacity to inform themselves of new data or the potential for new types of analysis. However, opening a new open data community or initiative in one’s own community would require a long-term plan in addition to short events.

If I met local open data activists in Thailand (my home country), my recommendations would actually be rather different from what I learned at the Canada Open Data Summit. Continuing on the thread from above, tackling transparency and accountability in countries experiencing endemic levels of corruption with the use of open data is perhaps a step too far. Solutions must always be appropriate and tailored to the locale. In the case of large digital divides (both in terms of broadband access and skills), gaps in education (both in society and in the public sector), and low quality in government data collection, it is really quite debatable whether or not open data is an appropriate or even cost effective solution to both social and economic problems. The first step to implementing open data and open government initiatives, is to think about democracy and its various forms. There is no single way to implement democratic government and I think this is an important point to recognise, as the open government and open data movement are, at the highest level, still ‘one size fits all’ movements. In the conversations during the week in Ottawa, there were only two situations mentioned where it was acceptable to withhold data – security/strategic assets and privacy. In countries like Thailand where democratic government is implemented very differently from Canada, open data activists in Thailand must be able to resolve the principles of open government and open data with their local contexts.

Thank you to the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation for their support with the RECODE programme, and thank you to Open North for their organisation of the Canada Open Data Summit.

For more summary of the events of the week, see our posts on the Canada Open Data Summit, IODC 2015 Day 1, and IODC 2015 Day 2.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, please get in touch with Suthee Sangiambut.