There is much hope expressed about the cultural, economic, political and social opportunities afforded by Geoweb and open data initiatives. Much of the fanfare focuses on how best to harness the power of information and communication technologies in order to beget the economic, political, and socio-cultural benefits that supposedly will follow. Such a view gives rise to two concerns. First, it places technology as the primary agent, or driver, of change. Second, it advances a form of historical amnesia about expectations for the democratic, economic, political, and social virtues of previous communication technologies, from electrification, through telegraph, radio, television, and the Internet, to mobile phones (see, Marvin 1990; Mattelart 1996; Mosco 2004; Standage 1998).

Geoweb and open data initiatives may enhance efficiencies, bring about greater transparency and foster enhanced levels of civic engagement. But this does not capture all the complexity. Such initiatives, and the technologies that enable them, are inherently political and their politics are directly impacted by the contexts within which stakeholder decisions are made about such things as the platforms to employ and the policies to implement. A cursory examination of the history of technology teaches us that, if we are to succeed in unraveling the myths about the supposed progressive and emancipatory powers of Geoweb and open data initiatives we need to be much more precise than all too frequently is advanced in mainstream accounts. Geoweb and open data initiatives operate within specific socio-economic and socio-cultural contexts.

We are collaborating with a graduate student from the University of Ottawa and colleagues from the Faculty of Information (iSchool) at the University of Toronto. The objective of

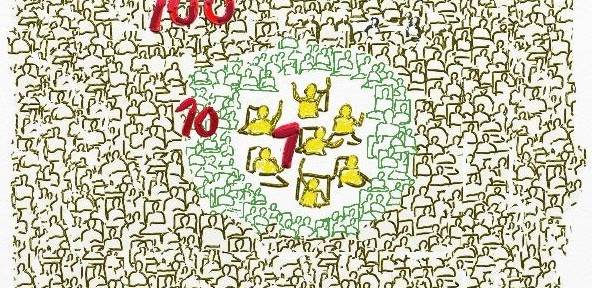

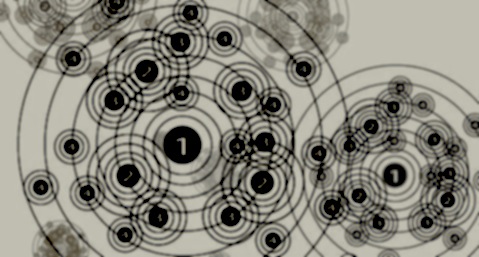

our project is to begin “mapping” the complex soci-political and economic terrain within which policy decisions about open data are made at federal, provincial and municipal levels. In these early stages the project has two principal objectives: identify key stakeholders (government, industry, civil society) in open data in Canada at federal, provincial and municipal levels; and create an electronic depository of policy documents, company reports, and NGO reports relating to open data in Canada.

Admin note: An underlying question at Geothink is whether there is there anything new with these geographically based Web 2.0 technologies? And do we believe that technology will rescue us from long-standing and difficult to realize processes like civic participation? At the same time, the technology appears new because it allows non-experts to share information—for us, geographically tagged information—and to contribute from anywhere, at anytime and do so anonymously. With the open data movement, government has taken unprecedented steps to release the raw data undergirding decision-making. Geothink will help us and help local governments to understand if there’s anything new going on.

If you have thoughts on this, please email Daniel Paré, dpar2@uOttawa.ca, and Leslie Shade, leslie.shade@utoronto.ca.