This post is cross-posted with permission from Daren C. Brabham, Ph.D. the personal blog of Daren C. Brabham. Brabham is a Geothink partner at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism where he was the first to publish scholarly research using the word “crowdsourcing.”

In this post, I provide an overview of crowdsourcing and a way to think about it practically as a problem solving tool that takes on four different forms. I have been refining this definition and typology of crowdsourcing for several years and in conversation with scholars and practitioners from diverse fields. Plenty of people disagree with my characterization of crowdsourcing and many have offered their own typologies for understanding this process, but I submit that this way of thinking about crowdsourcing as a versatile problem solving model still holds up.

I define crowdsourcing as an online, distributed problem solving and production model that leverages online communities to serve organizational goals. Crowdsourcing blends bottom-up, open innovation concepts with top-down, traditional management structures so that organizations can effectively tap the collective intelligence of online communities for specific purposes. Wikis and open source software production are not considered crowdsourcing because there is no sponsoring organization at the top directing the labor of individuals in the online community. And when an organization outsources work to another person–even if that work is digital or technology-focused–that is not considered crowdsourcing either because there is no open opportunity for others to try their hands at that task.

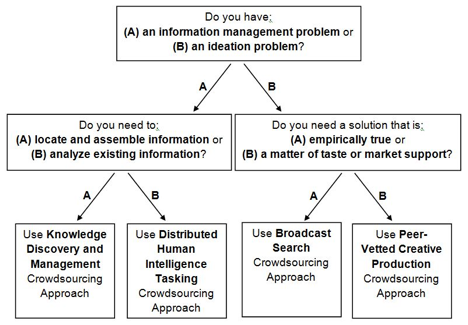

There are four types of crowdsourcing approaches, based on the kinds of problems they solve:

1. The Knowledge Discovery and Management (KDM) crowdsourcingapproach concerns information management problems where the information needed by an organization is located outside the firm, “out there” on the Internet or in daily life. When organizations use a KDM approach to crowdsourcing, they issue a challenge to an online community, which then responds to the challenge by finding and reporting information in a given format back to the organization, for the organization’s benefit. This method is suitable for building collective resources. Many mapping-related activities follow this logic.

2. The Distributed Human Intelligence Tasking (DHIT) crowdsourcing approach concerns information management problems where the organization has the information it needs in-hand but needs that batch of information analyzed or processed by humans. The organization takes the information, decomposes the batch into small “microtasks,” and distributes the tasks to an online community willing to perform the work. This method is ideal for data analysis problems not suitable for efficient processing by computers.

3. The Broadcast Search (BS) crowdsourcingapproach concerns ideation problems that require empirically provable solutions. The organization has a problem it needs solved, opens the problem to an online community in the form of a challenge, and the online community submits possible solutions. The correct solution is a novel approach or design that meets the specifications outlined in the challenge. This method is ideal for scientific problem solving.

4. The Peer-Vetted Creative Production (PVCP) crowdsourcing approach concerns ideation problems where the “correct” solutions are matters of taste, market support, or public opinion. The organization has a problem it needs solved and opens the challenge up to an online community. The online community then submits possible solutions and has a method for choosing the best ideas submitted. This way, the online community is engaged both in the creation and selection of solutions to the problem. This method is ideal for aesthetic, design, or policy-making problems.

This handy decision tree below can help an organization figure out what crowdsourcing approach to take. The first question an organization should ask about their problem solving needs is whether their problem is an information management one or one concerned with ideation, or the generation of new ideas. In the information management direction, the next question to consider is if the challenge is to have an online community go out and find information and assemble it in a common resource (KDM) or if the challenge is to use an online community to process an existing batch of information (DHIT). On the ideation side, the question is whether the resulting solution will be objectively true (BS) or the solution will be one that will be supported through opinion or market support (PVCP).

A decision tree for determining appropriate crowdsourcing approaches for different problems. Source: Brabham, D. C., Ribisl, K. M., Kirchner, T. R., & Bernhardt, J. M. (2014). Crowdsourcing applications for public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(2), 179-187.

I hope this conception of crowdsourcing is easy to understand and practically useful. Given this outlook, the big question I always like to ask is how we can mobilize online communities to solve our world’s most pressing problems. What new problems can you think of addressing with the power of crowds?

Daren C. Brabham, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism at the University of Southern California. He was the first the publish scholarly research using the word “crowdsourcing,” and his work focuses on translating the crowdsourcing model into new applications to serve the public good. He is the author of the books Crowdsourcing (MIT Press, 2013) and Crowdsourcing in the Public Sector (Georgetown University Press, 2015).