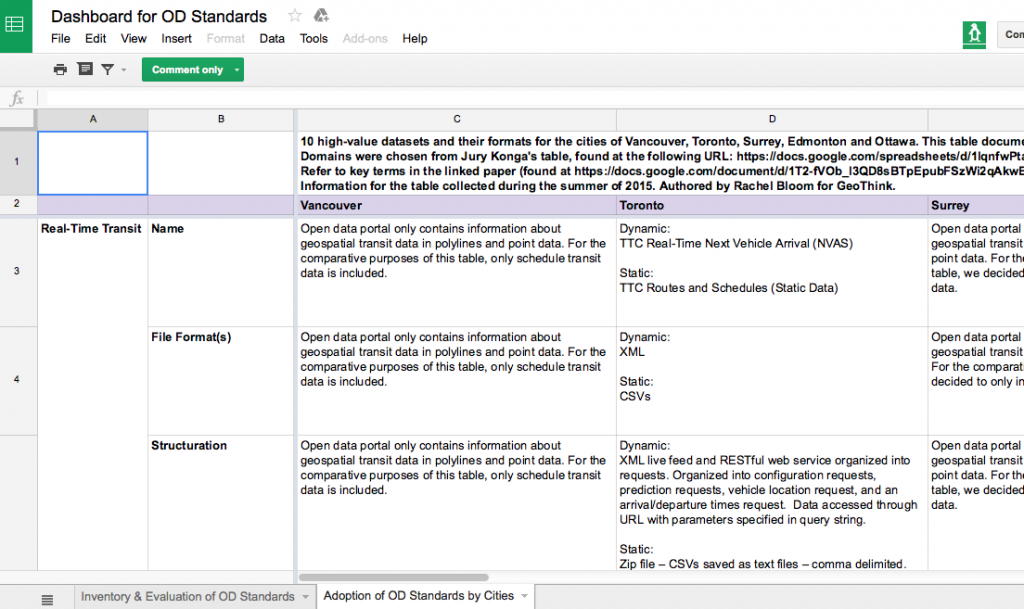

- The first spreadsheet, Adoption of Open Data Standards By Cities, evaluates ‘high value’ datasets specific to 10 domains on the open data catalogues for the cities of Vancouver, Toronto, Surrey, Edmonton, and Ottawa.

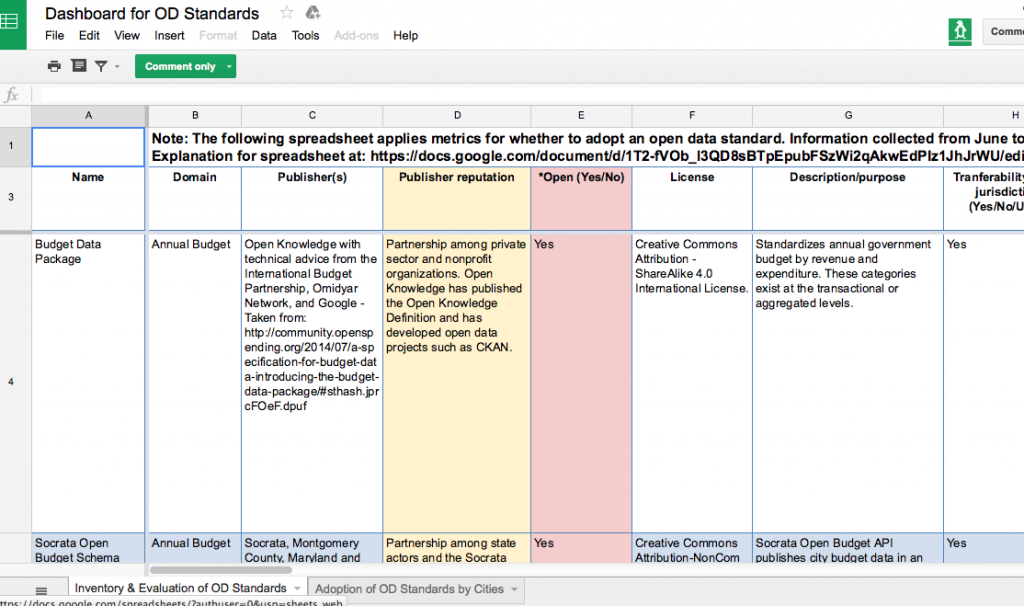

- The second spreadsheet, An Inventory and Evaluation of Open Data Standards, catalogues and evaluates 22 open data standards that are available for domain-specific data.

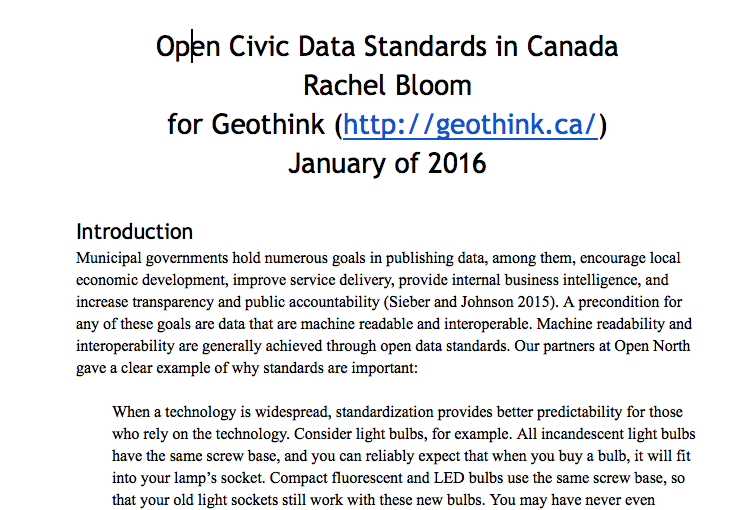

- An accompanying white paper explains the two spreadsheets and the primary objective of Geothink’s Open Data Standards Project.

By Rachel Bloom

Rachel Bloom is a McGill University undergraduate student and project lead for Geothink’s Open Data Standards Project.

In February, I led a Geothink seminar with city officials to introduce the results of our open data standards project we began approximately one year earlier. The project was started with the objective of assisting municipal publishers of open data in standardizing their datasets. We presented two spreadsheets: the first was dedicated to evaluating ‘high-value’ open datasets published by Canadian municipalities and the second consisted of an inventory of open data standards applicable to these types of datasets.

Both spreadsheets enable our partners who publish open data to know what standards exist and who uses them for which datasets. The project I lead is motivated by the idea that well-developed data standards for city governance can grant us the luxury of not having to think about the compatibility of technological components. When we screw in a new light bulb or open a web document we assume that it will work with the components we have (Guidoin and McKinney 2012). Technology, whether it refers to information systems or manufactured goods, relies on standards to ensure its usability and dissemination.

Municipal governments that publish open data look to the importance of standards for improving the usability of their data. Unfortunately, even though ‘high-value’ datasets have increasingly become available to the public, these datasets currently lack a consensus about how they should be structured and specified. Such datasets include crime statistics and annual budget data that can provide new services to citizens when municipalities open such datasets by publishing them to their open data catalogues online. Anyone can access such datasets and use the data however they wish without restriction.

Civic data standards provide agreements about semantic and schematic guidelines for structuring and encoding the data. Data standards specify technical data elements such as file formats, data schemas, and unique identifiers to make civic data interoperable. For example, most datasets are published in CSV or XML formats. CSV structures the data in columns and rows, while XML encapsulates the data in a hierarchical tree of <tags>.

They also specify common vocabularies in order to clarify interpretation of the data’s meanings. Such vocabularies could include, for example, definitions for categories of expenditure in annual budget data. Geothink’s Open Data Standards Project offers publishers of open data an opportunity to improve the usability and efficiency of their data for consumers. This makes it easier to share data across municipalities because the technological components and their meanings within systems will be compatible.

Introducing Geothink’s Open Data Standards Project

No single, clear definition of an open data standard exists. In fact, most definitions of an ‘open data standard’ follow two prevailing ideas: 1) Standards for open data; 2) And, open standards for data. Geothink’s project examines and relates together both of these prevailing ideas (Table 1). The first spreadsheet, the ‘Adoption of Open Data Standards By Cities’, considers open data and its associated data standards. The second spreadsheet, the ‘Inventory of Open Data Standards,’ considers the process of open standardization. In other words, we were curious about what standards are currently being applied to open municipal data, and how to break down and document open standards for data in a way that is useful to municipalities looking to standardize their open data.

Table 1: Differences between ‘open data’ standards and open ‘data standards’

| Requires open data | Requires open standard process | |

| Evaluation of ‘High-Value’ Datasets | Yes | No |

| Inventory of Open Data Standards | No | Yes |

The project’s evaluation of datasets relates to standards for open data. Standards for open data refer to standards that, regardless of how they are developed and maintained, can be applied to open data. Open data, according to the Open Knowledge Foundation (2014), consists of raw digital data that should be freely available to anyone to use, repurposable and re-publishable as users wish, and absent mechanisms of control like restrictive licenses. However, the process of developing and maintaining standards for open data may not require transparency nor include public appeals for its development.

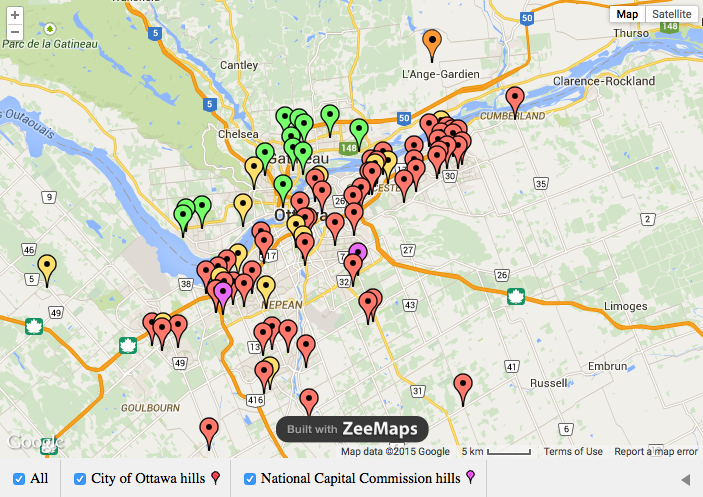

To discover what civic data standards are currently being used, the first spreadsheet, Adoption of Open Data Standards By Cities, evaluates ‘high value’ datasets specific to 10 domains (categories of datasets such as crime, transportation or or service requests) in the open data catalogues for the cities of Vancouver, Toronto, Surrey, Edmonton and Ottawa. The types of data were chosen based on the Open Knowledge Foundation’s choice of datasets considered to provide greatest utility for the public. The project’s spreadsheet notes salient structuring and vocabulary of each dataset; such as the name, file format, schema, and available metadata. It especially notes which data standards these five municipalities are using for their open data (if any at all).

With consultation from municipal bodies and organizations dedicated to publishing open data, we developed a second spreadsheet, Inventory and Evaluation of Open Data Standards, that catalogues and evaluates 22 open data standards that are available for domain-specific data. The rows of this spreadsheet indicate individual data standards. The columns of this spreadsheet evaluate background information and quality for achieving optimal interoperability for each of the listed standards. Evaluating the quality of the standard’s performance, such as whether the standard is transferable to multiple jurisdictions, is an important consideration for municipalities looking to optimally standardize their data. Examples of open data standards in this inventory are BLDS for building permit data and the Budget Data Package for annual budget data.

The project’s second spreadsheet is concerned with open standards for data. Open standards, as opposed to closed standards, requires a collaborative, transparent, and consensus-driven process to maintain its development (Palfrey and Gasser, 2012). Therefore, open standards honor a commitment to processes of transparency, due process, and rights of appeal. Similarly to open data, open standards resist processes of unchecked, centralized control (Russell, 2014) . Open data standards make sure that end users do not get locked into a specific technology. In addition, because open standards are driven by consensus, they are developed according to the needs and interests of participatory stakeholders. While we provide spreadsheets on both, our project advocates implementing open standards for open data.

In light of the benefits of open standardization, the metrics of the second spreadsheet note the degree of openness for each standard. Such indicators of openness include multi-stakeholder participation and a consensus-driven process. Openness may be observed through the presence of online forums to discuss suggestions or concerns regarding the standard’s development and background information about each standard’s publishers. In addition, open standards use open licenses that dictate the standards may be used without restriction and repurposable for any use. Providing this information not only allows potential implementers to be aware of what domain-specific standards exist, but also allows them to gauge how well the standard performs in terms of optimal interoperability and openness.

Finally, an accompanying white paper explains the two spreadsheets and the primary objective of my project for both publishers and consumers of open data. In particular, it explains the methodology, justifies chosen evaluations, and notes the project’s results. In addition, this paper will aid in navigating and understanding both of the project’s spreadsheets.

Findings from this Project

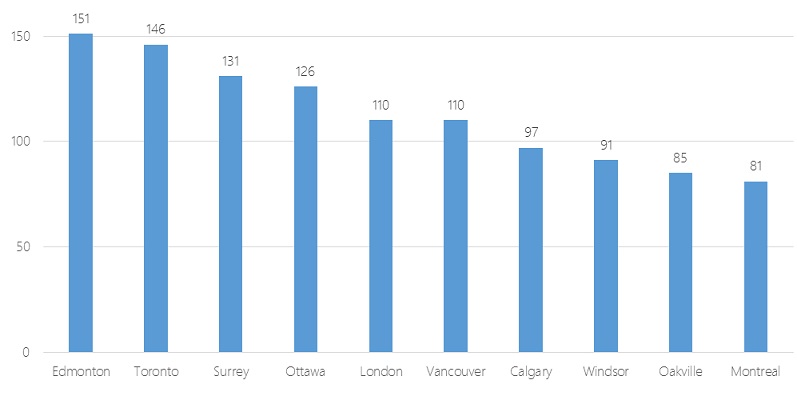

My work on this project has led me to conclude that the majority of municipally published open datasets surveyed do not use civic data standards. The most common standard used by municipalities in our survey was the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) for transit data and the Open311 API for service request data. Because datasets across cities and sectors vary formats and structure, differences in them coupled with a lack of cohesive definitions for labeling indicate standardization across cities will be a challenging undertaking. Publishers aiming to extend data shared among municipalities would benefit from collaborating and agreeing on standards for domain-specific data (as is the case with GTFS).

Our evaluation of 22 domain-specific data standards also shows standards do exist across a variety of domains. However, some domains, such as budget data, contain more open data standards than others. Therefore, potential implementers of standards must reconcile which domain-specific standard best fits their objectives in publishing the data and providing the most benefits for public good.

Many of standards also contain information for contacting the standard’s publishers along with online forums for concerns or suggestions. However, many still full information regarding their documentation or are simply in early draft stages. This means that although standards exist, some of these standards are in their early stages and may not be ready for implementation.

Future Research Pathways

This project has room for growth so that we can better our partners who publish and use open data decide how to go about adopting standards. To accomplish this goal, we could add more cities, domains, and open standards to the spreadsheets. In addition, any changes made to standards or datasets in the future must be updated.

In terms of the inventory of open data standards, it might be beneficial to separate metrics that evaluate openness of a standard from metrics that evaluate interoperability of a standard. Although we have emphasized the benefits of open standardization in this project, it is evident that some publishers of data do not perceive openness as crucial for the successfulness of a data standard in achieving optimal interoperability.

As a result, my project does not aim to dictate how governments implement data standards. Instead, we would like to work with municipalities to understand what is valued within the decision-making process to encourage adoption of specific standards. We hope this will allow us to provide guidance on such policy decisions. Most importantly, to complete such work, we ask Geothink’s municipal partners for input on factors that influence the adoption of a data standard in their own catalogues.

Contact Rachel Bloom at rachel.bloom@mail.mcgill.ca with comments on this article or to provide input on Geothink’s Open Data Standards Project.

References

Guidoin, Stéphane and James McKinney. 2012. Open Data, Standards and Socrata. Available at http://www.opennorth.ca/2012/11/22/open-data-standards.html. November 22, 2012.

Open Knowledge. Open Definition 2.0. Opendefinition.org. Retrieved 23 October 2015, from http://opendefinition.org/od/2.0/en/

Palfrey, John Gorham, and Urs Gasser. Interop: The promise and perils of highly interconnected systems. Basic Books, 2012.

Russell, Andrew L. Open Standards and the Digital Age. Cambridge University Press, 2014.