Day two of Geothink’s 2017 Summer Institute at McGill University in Montreal, QC featured presentations by faculty on the pressing issues facing smart cities.

By Drew Bush

On day two of Geothink’s 2017 Summer Institute at McGill University in Montreal, QC, students got their hands dirty investigating the important issues facing smart cities. Each group presented unique findings in answer to a question they were asked to investigate from the disciplines of law, geomatics and geography.

The theme of this year’s Institute was “Smart City: Toward a Just City.” An interdisciplinary group of faculty and students tackled many of the policy, legal and ethical issues related to smart cities. Each of the three days of the Summer Institute combined workshops, panel discussions and hands-on learning modules that culminated in a competition judged by Montreal city officials and tech entrepreneurs. The goal of the competition was for student groups to develop and assess the major principles guiding Montreal’s 2015-2017 Montréal Smart and Digital City Action Plan.

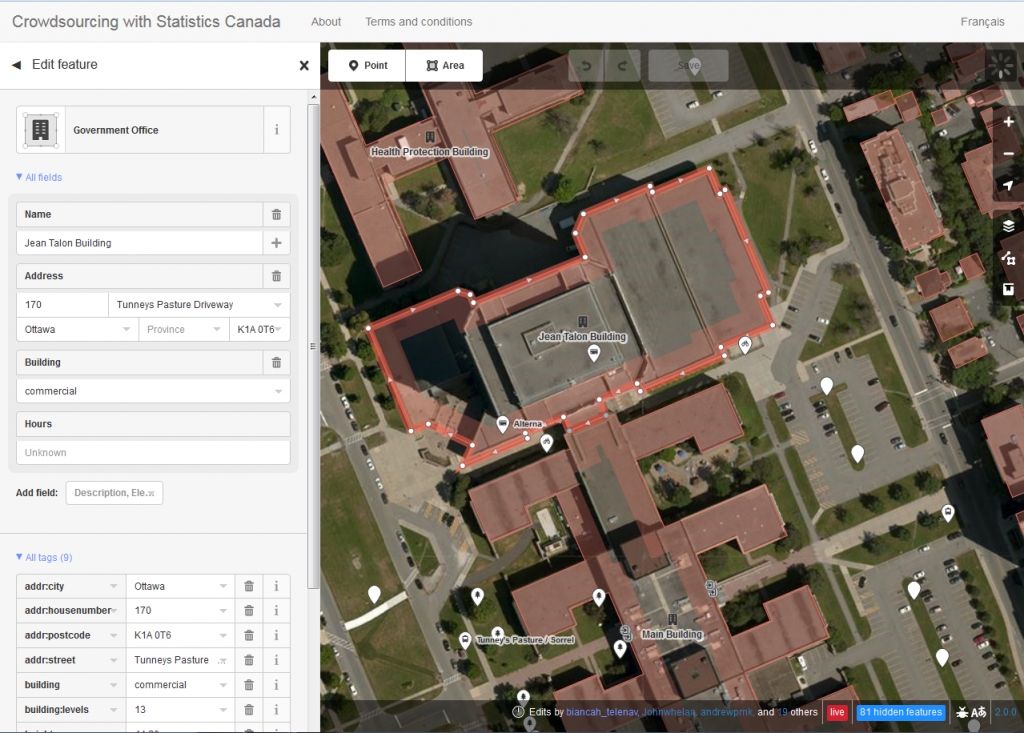

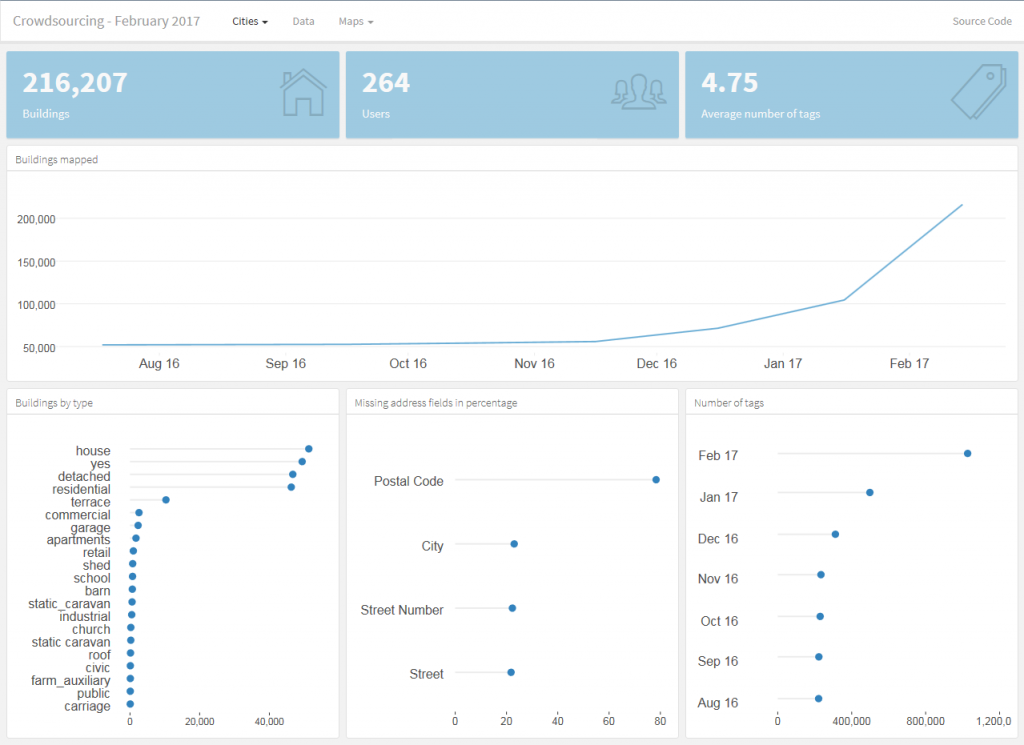

Before undertaking their own research, students heard from Institute faculty with expertise in each of the areas they were asked to investigate during half-hour presentations. This began with a presentation on the online, participatory mapping tool, GeoLive, by Geothink Co-Applicant Jon Corbett, associate professor in University of British Columbia at Okanagan’s Department of Geography. He was followed by Geothink Co-Applicant Teresa Scassa, Canada research chair in University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law, who talked about the legal issues surrounding the development of applications (APPs) in smart cities. Geothink Co-Applicant Stéphane Roche, associate professor in University Laval’s Department of Geomatics, finished the morning by talking about ethics in smart cities.

“So law is in many respects about relationships, and certainly in this context is about relationships,” Scassa told students during her presentation. “And so one of the things you need to do when you are looking at and thinking about legal issues in this context is to think about what particular legal relationship or relationships you are talking about and you are thinking about. So, for example, a city may be thinking about entering into a contract with a particular service provider for a smart city’s service or a smart city’s APP. And that—there will be a relationship defined in legal terms between the city and the service provider at that point. And so that’s one relationship.”

“And there are going to have to be certain things worked out in the context of that particular relationship between the city and the service provider,” Scassa added. “The city that enters into a contract for that service may then also have a relationship with the users of that service. And so that’s another relationship. And it’s a relationship the city has to think about in terms of how it wants to define that relationship with its users.”

“There are two things that I really appreciate,” Geothink Co-Applicant Stéphane Roche, associate professor in University Laval’s Department of Geomatics, said. “The first one is the idea of talking about and thinking about smart cities without talking about smart cities. And that was the case this morning. And especially by—with the first presentation by [Jon Corbett]. I guess that what Jon has presented, you know, about participatory mapping for a community was and is really valuable for our reflection about smart cities.”

“It’s not a question of technology,” Roche added before noting that the second thing he appreciated was the interdisciplinarity of the presentations and students. “The main issue is involving community. The main issue is designing solutions that are in line with their view of space—[a community’s] view of their relationship with space.”

At the conclusion of the presentations, each student group was presented with a unique question that they had to answer. Questions were derived from each discipline and speaker’s presentation. They asked students to conduct research on how society should evaluate the usability and functionality of smart city APPs and how the additional data and APPs from a smart city create legal liability for cities that doesn’t fit within the policy structure that already exists.

“We are assessing the impact of like, I guess, the Geolive initiative,” Selasi Dokenoo, an undergraduate student at Ryerson University, said. “To clarify what it’s like and how do we assess the impact and benefits of this type of program.”

A different group worked with another site, iSearch Kelowna, for their question. The Web site makes use of open data to aid people in finding low-income rentals, supportive housing or emergency shelters within the City of Kelowna.

“For the exercise, the question is related to feedback,” Ali Afghanteloee, a doctoral student at Laval University, said. “Evaluating the functionality and usability of the web services about Kelowna. First of all, we’ve found out what is the criteria [for] evaluation. And, second, what are the tools to evaluate this kind of criteria. It’s just—we decided that, I think, that the quality criteria is very important because we decided that the user is very important. The usability. And spatially whether creating this site to find out what the services are—whether this is useable or not.”

The day concluded with each group presenting findings on what they had found during their research. For many, this proved enlightening and related well to their own work back at their home university.

Student groups worked on day two to answer research questions posed by the panelists about smart cities.

“Well, I’m interested in policy mobility,” Brennan Field, a doctoral student at University of Saskatchewan, said. “So it’s been interesting in the past few days just looking at how smart cities, in terms of an urban policy space, have become mobile and have been spreading. And so in the case of the Montreal it was interesting hearing [Harout Chitilian] speaking of how the police department is using open data to report crime. And then their initial reticence and then kind of opening up to it. So I was already familiar with that—basically that has been how police departments generally respond to that particular policy. The policy of open data related to reporting police activity.”

“And seeing how a lot of it is cross-overs between how open data as urban policy has become mobile and how smart cities as urban policy has become mobile,” Field added. “So there are a lot of similarities and cross-overs with my research. So that’s what I’ve learned.”

###

If you have thoughts or questions about the article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.