Image courtesy of http://webmedia.jcu.edu/

The rise of big data that is geospatially referenced enables organizations and individuals to utilize new analytical techniques and approaches to identify patterns of social inequity and organize resources to address and correct these inequities where they exist. The range of social issues where the “data of social justice” can provide a deeper understanding of the scope and magnitude of inequities extends across complex issues including global hunger and disease, income and social inequality, criminal justice and mass incarceration, legal reform, ecology and climate change, political unrest and social change, and economics and productivity. Geothink’s researchers have used big data, crowdsourced data, and new open datasets in conjunction with mapping technologies, applications (apps), and Web 2.0 software to analyze social problems and provide practical solutions. This work has included improving urban accessibility for those living with disabilities and helping the homeless to more easily find urban services. This panel of experts brought together leading academic experts to discuss the opportunities, challenges, and implications of this work with a focus on its application in cities across the world.

On Friday, January 26 at 12:00 (EST), Geothink.ca held its fifth monthly Geothink&Learn video conference session on the topic of governing artificial intelligence. It highlighted Geothink’s unique interdisciplinary perspective and included a myriad of ideas from our faculty, students and partners. (Catch a recording of this session below along with a transcript of the written question and answer session.)

The convener for the session was Geothink Co-Applicant Jon Corbett, an associate professor at University of British Columbia, Okanagan’s Department of Community, Culture and Global Studies. Speakers included Geothink Co-Applicant Rob Feick, an associate professor in University of Waterloo’s School of Planning; Joanna Redden, a lecturer in Cardiff University’s School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies; Alessandra Renzi, an associate professor in Communication Studies at Concordia University; and, Victoria Fast, an assistant professor in University of Calgary’s Department of Geography.

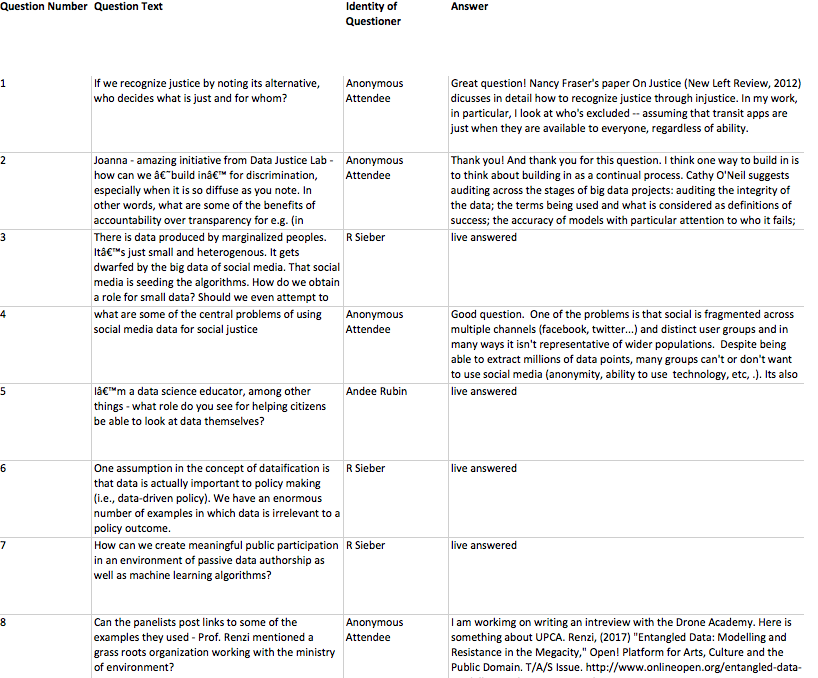

A question and answer session followed after presentations conclude. Our five panelists briefly introduced their research and then reflected on the role of artificial intelligence in governance.

When:

Friday January 26, 2018 at 12:00 PM [NOW CONCLUDED]

Where:

https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_mO59cEmRTMGKOW5HMq66Pg

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the webinar.

Convener:

Jon Corbett

Moderator:

Drew Bush

Download a poster of this event to share with colleagues.

Panelists:

Jon Corbett: Increasingly open data are being used to both directly and indirectly support social justice, social change, and other activism issues. However, for many communities wanting to benefit from open data the moments when the data is of tangible benefit rarely justify a continued impetus to mine, scrape and make sense of the changing dataset. Additionally, the benefits of open data only reach their full potential when juxtaposed with community data – thus, especially in a First Nation context, leading to a fundamental tension between open and closed data. Furthermore, in a development environment where much of the innovative work being done to leverage open data is embedded within the capricious ‘start up’ culture, researchers, businesses and even government aspire to produce ‘political messaging’ presented through eye-catching visualizations, however the impact of these messages are often fleeting and rarely support the day-to-day needs of communities. It is hard to see where social justice is positioned as a central principle of the open data movement. So, I ask the question, is open data for social justice being design driven, or is it framed around specific needs?

Victoria Fast: The smart city promise rests on the idea that more and better information and communication technologies can make cities “smarter”, i.e. improve the efficiency and sustainability of cities, from the scale of the individual to large city-regions. However, many smart city technologies—Uber, Google Maps, and Yelp for example—inequitably serve society, and notably underserve people with disabilities. Drawing on research themes related to smart and socially just cities, spatial and open data infrastructure, and accessibility analytics, I investigate how smart spatial accessibility can enable more equitable access to digital mobility services. More broadly, it is important to ask: how can emerging technologies be leveraged to benefit all Canadians, including Canadians living with disabilities?

Joanna Redden: Argued that as governments make more use of big data systems and artificial intelligence there is need for greater transparency, accountability and means for citizen interventions. She drew upon two ongoing research projects to make this case, the first investigates the Government of Canada’s uses of big data and the second is a transnational study of data harms.

Rob Feick: Big geodata, coupled with data-driven analysis, provide new methods for decision makers to understand community needs and for citizens to create spatial data by using participatory web apps and, indirectly, by interacting with each other (e.g. social media) and with urban sensor systems (e.g. transit smart cards). The emerging role of the citizen as a data producer has important implications for equity in community participation since only some interests and some areas are represented in these digital data traces. In this context, we need to ask: how can we apply these new data-driven analysis methods to community decision making in Canada, while safeguarding equity, well-being and individuals’ opportunities?

Alessandra Renzi: Discussed the results of a research-creation project carried out in Jakarta, Indonesia with the Urban Poor Consortium. The collaboration took place over three years and involved the collection and visualization of data about flooding and evictions of the informal settlements along the river Ciliwung. The case study shows how the urban poor are creatively engaging in data production and mobilization in their struggle for social justice.

Alessandra Renzi: Discussed the results of a research-creation project carried out in Jakarta, Indonesia with the Urban Poor Consortium. The collaboration took place over three years and involved the collection and visualization of data about flooding and evictions of the informal settlements along the river Ciliwung. The case study shows how the urban poor are creatively engaging in data production and mobilization in their struggle for social justice.