By Jin Xing

I was one of three Geothink students who competed in the Environmental Systems Research Institute’s (ESRI) ECCE 1st Annual App Challenge hosted by the institute’s Canada Centre of Excellence. Team CODE-McGill, which consisted of McGill University students Matthew Tenney, Carl Hughes, and myself placed second in the competition that concluded on March 20 with the announcement of a winning group from the University of Waterloo.

Although our three team members each has a different research interest, each of us studies topics related to open data. Our Community Open Data Engage (CODE) application was sparked by an exchange I had with Hughes when we discovered we both call Toronto, Ontario home after the competition had already begun. In fact, it was only after Hughes told me that my neighbourhood was “a better” place to live that we began to interrogate the question of how to evaluate a community using open data.

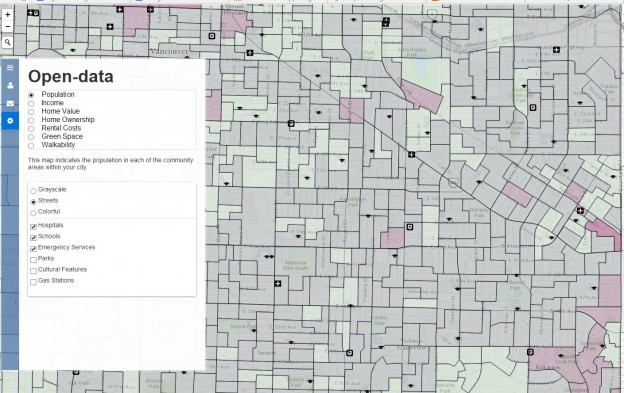

As we worked on our submission, we noticed that community-level open data attracts more attention than data on the whole city. In particular, we found citizens were more concerned with data on traffic, education, and recreation resources in their own neighbourhoods compared to other types of data. Our creation: A new approach for exploring a community using an open data platform that connects people and communities.

However, the application that we designed required a number of trade-offs to be decided in the span of only one week. First, we struggled to choose whether to include more data or to favour an easy-to-use interface. In particular, we wanted to develop functionality to integrate a greater variety of community data but didn’t want the application to become too hard to use. After several hours of discussion, we decided to favour an approach that centered on making open data “easy and ready to use.”

The second trade-off involved the selection of ESRI JavaScript APIs. In particular, we had to choose ESRI ArcGIS API or ESRI Leaflet for open data integration and visualization. At the beginning, I preferred the ArcGIS API due to its rich functions. But Tenney pointed out it was actually over-qualified and may delay the page loading which caused the team to decide to use Leaflet.

Finally, we had to decide how to integrate social media. In particular, we needed to decide whether the Twitter content should be loaded from data streaming or just retrieved from the back-end. All of us felt it was cool to have a real-time Twitter widget on our application’s page, but we didn’t know how to get it to choose the right tweets. For example, a user named Edmonton might say nothing about the City of Edmonton city, and our code would have needed to filter it out in real-time. Considering the difficulty of developing such a data filtering AI in one week, we decided to include it only on the back-end. To accomplish this, we used Python to develop a way to harvest and process data, while the ESRI Leaflet handled all the front-end data integration and visualization.

Our application included data on school locations, health facility locations, grocery store locations, gas station locations, green space, cultural facilities, emergency services, census dissemination areas and Twitter data, all of which were presented as different map layers. We employed the Agile developing method for CODE, meaning we quickly built the prototype for CODE and tested it, then repeated this process with additional functions or by re-developing bad code.

In actuality, though, we built three prototypes in the first two days and spent another two days for testing, selecting and re-developing. The Agile method helped us keep CODE always functional and easy to extend. The only drawback of using Agile was the local code synchronization become necessary before we pushed it to GitHub. If two of us pushed at the same time with different code, our GitHub would be massed up. By late Thursday night, we had nearly finished all the planned coding and had even begun to improve the user experience. The search widget and navigation buttons were added in the last day to make open data easy and ready for use in our CODE application.

We felt that by putting information in the hands of concerned citizens and community leaders, CODE is a proof-of-concept for data-driven approaches to building a strong sense of communityacross cities. CODE also connects people and governments by allowing them to create forums for conversation in specific communities across a city or search social media sites to find other people in their area.

Furthermore, by integrating and visualizing open data at a community scale, CODE demonstrates a new approach for community exploration. In fact, users can search and select different open data for certain communities on one map, and corresponding statistics are shown as pop-ups. In the initial phase, we provided this community exploration service for citizens in Edmonton and Vancouver.

Overall, I felt attending this ECCE App challenge was a great experience to integrate ESRI web technologies with open data research. It proves open data can act as the bridge between citizen and cities, and that ESRI products significantly simplify the building of just such a bridge. We believe more applications will continue to be inspired by the ECCE App challenge and that open data will become closely used in everyday life. Thanks to ESRI, we got a chance to help shape the next-generation of community exploration.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Jin Xing, Geothink’s Information Technology Specialist, at jin.xing@mail.mcgill.ca.