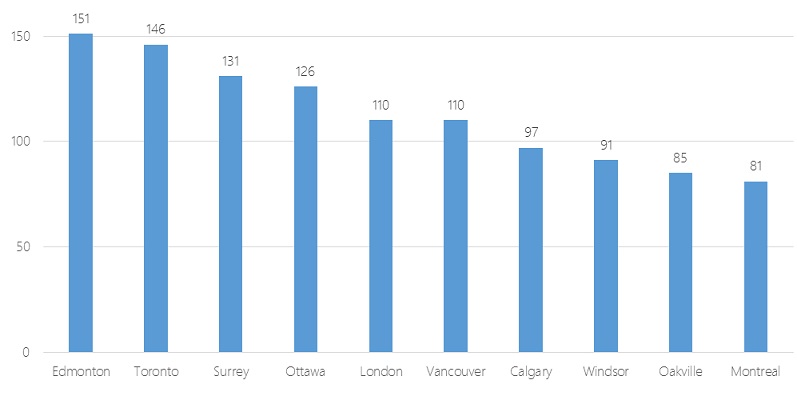

Rankings of Canada’s Top 10 cities out of possible max scores of 193 in Public Sector Digest’s 2015 Open Cities Index (Image courtesy of Public Sector Digest).

By Drew Bush

Numerous city, state, and provincial governments across North America are finding new ways to share government data online. With more than 60 nations now part of the Open Government Partnership, it’s often difficult to determine which initiatives are simply part of a growing fad instead of being true attempts at more responsive and accountable government.

In the United States, President Barak Obama announced plans in 2009 to make many federal agencies open by default with government information, yet just last month the office charged with carrying out this directive failed to openly publish a schedule for its guidelines on this work. In Canada, a variety of city initiatives aim to allow citizens to more easily view crime statistics, find out information about neighborhood quality of life, or time the arrival of the next bus. With so many initiatives, it can be difficult to determine which best improves municipal responsiveness or offers new services to citizens particularly amidst promises by the newly elected Liberal government on open data (see Tweet below).

#opendata, #opengov, & easier access to public data – important points in @JustinTrudeau's 32-point plan from June https://t.co/BYSl8rwy7g

— Geothink.ca (@geothinkca) October 20, 2015

The authors of Public Sector Digest’s first ever 2015 Open Cities Index aim to solve this problem by providing “a reference point for the performance” of open data programs in 34 Canadian cities. The authors of the index undertook a survey to measure 107 variables related to open data programs. In particular, the index measures three types of data sets cities may have made available: those related to accountability (e.g. elections or budget data), innovation (e.g. traffic volume or service requests), and social policy (e.g. crime rates or health performance).

Across each data set in these three categories, municipalities were scored on five variables according to questions such as whether their data sets are available online, machine readable, free, and up-to-date. The aim was to help these municipalities, which often have limited resources to spend on open data programs, to assess their strengths and weaknesses and improve open data programs.

Four Geothink partner cities made the top 10 of the index, with Edmonton in first place, Toronto second, Ottawa fourth, and Vancouver sixth. At last year’s Canadian Open Data Summit, Edmonton also won the Canadian Open Data Award. You can find the full list of city rankings on the report’s home page. Yet the value of these types of ratings and awards will only be shown over time, according to many practitioners in the field.

“It’s hard to tell what it means to be ranked fourth because it’s a brand new thing,” said Robert Giggey, the coordinator and lead for the City of Ottawa’s Open Data program. “It’s not something that’s done every year, every month, that everybody knows about and is waiting for. So it’s kind of yet to be determined.”

The Value of the Index

Other indexes have measured open data at the national level, such as the Open Data Barometer. And measurements of municipal open data undertaken by two university students focused only on what types of data sets were available. The Open Cities Index works to take this a step further by engaging with key areas of interest. In particular, the index aims to standardize measurements around three themes:

1. Readiness—To what extent is the municipality ready/capable of fostering positive outcomes through its open data initiative?

2. Implementation—To what extent has the city fulfilled its open data goals and ultimately, what data has it posted online?

3. Impact—To what extent has the posted information been used, what benefits has the city accrued as a result of its open data program, and to what extent is the city capable of measuring the impact?

One Geothink researcher cautions, however, that it’s difficult to ascertain the worth of the index until its authors make the full report available along with more information on the 107 variables surveyed. In particular, he said, implementation can be a difficult metric to measure because different cities have different data collection responsibilities and different goals.

“I’m working on some research right now that shows that governments don’t actually have very good tracking metrics for use,” Peter Johnson, assistant professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Management at the University of Waterloo, wrote in an e-mail to Geothink.ca. “Much of their sense of who uses open data and what it is used for is anecdotal and certainly incomplete. Since open data is provided with few restrictions, it is difficult to track who is using it and what it is being used for in any comprehensive way.”

Beyond the data online now, cities interested in being included in future years of the index and accessing a detailed analysis of municipal open data programs across Canada must contact Public Sector Digest. Some municipalities, like Ottawa, may wait and see how it goes in those places that have already paid for the service, according to Giggey.

“I want to see what the reaction is from the open data community, from other jurisdictions, from other areas—Geothink—about what they think of the index,” he said. “Is this any good? Is it worth anything? Then we’ll look to see if it’s something we want to invest in.”

The Reaction Among Geothink Partner Cities

The value of the index will be determined as more details on its methodology and conclusions are released, and, perhaps, it becomes a regular measure of open data work in Canada’s municipalities. For now city staff in charge of open data work in the cities interviewed by Geothink.ca agree that the index does achieve the goal of bringing recognition to the work they are doing. In Ottawa, this has included work to make the city accountable by providing datasets on elected officials, budget data, lobbyist and employee information, and 311 calls. Toronto got a relatively early start with city budgets in 2009 and now also has a portal with social data on neighborhoods (including datasets like demographics, public health, and crime rates).

“I am glad the index recognizes the time and effort each city puts in to make its data open and accessible for reuse and repurpose,” Linda Low, open data coordinator for the City of Vancouver, wrote in an e-mail. Datasets in her city include information on crime, business licenses, property tax, Orthophoto imagery, and census local areal profiles. “This doesn’t happen overnight and it certainly is a team effort to get to where we are today.”

Edmonton’s recognition for its work derives from a 2010 decision by city leaders to launch an open data catalogue and the 2011 awarding of a $400,000 IBM Smart Cities Challenge award grant. Work in the city has included using advanced analysis of open data streams to enhance crime enforcement and prevention, an “open lab” to provide new products that improve citizen interactions with government, and interactive neighbourhood maps that will help Edmontonians locate and examine waste disposal services, recreational centres, transit information, and capital projects. More can be found on Edmonton’s work in a previous Geothink article.

“We are thrilled and honoured that our innovation and hard work have been recognized,” Yvonne Chen, a strategic planner for the City of Edmonton, wrote in an e-mail. She noted that Edmonton’s success, which results directly from a city council policy on open data, includes having an online budget tool that increases transparency about the allocation of public funds. “Our goal has always been to be a leader in the Canadian open government movement.”

While the recognition helps bring attention to the work being done by cities, much remains to be seen about how well the index actually compares cities against each other when objectives and the types of data recorded can vary greatly.

“It’s great to be in the top 10 any time, but we know from when we got the survey sent to us, we weren’t sure of all their measures that they were taking,” Keith McDonald, open data lead for the City of Toronto, said.

“We’d like to see other studies and maybe a little more apples to apples comparison for sure,” he added. “I think actually that was the intent—I can’t speak for the Public Sector Digest—but I think that was the intent of having an ongoing group that would buy into their measuring, so that people could continue to tweak and make it a stronger real apples to apples comparison. And we would support that.”

In fact, the value of an index like this one may lie in allowing cities to track their own progress over time.

“For all those cities included (and even those that aren’t) it can help to narrow the field as to where effort may be best placed to improve open data provision,” Johnson wrote of what he called a “high-profile external evaluation” of each city’s work.

If you have thoughts or questions about this article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.